'Faustian bargain': defence fears over Australian university's $100m China partnership

University of New South Wales says it has conducted due diligence and concerns about research being used for military purposes are drawing ‘a very long bow’

A world-first collaboration between the University of New South Wales and the Chinese government, celebrated as a $100m innovation partnership, opens a Pandora’s box of strategic and commercial risks for Australia, according to leading analysts.

These include the potential loss of sensitive technology with military capability, an unhealthy reliance on Chinese capital and vulnerability to Beijing’s influence in Australia’s stretched research and technology sector.

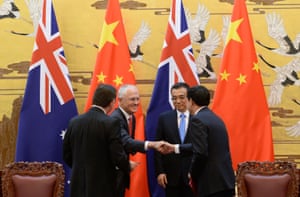

The UNSW Torch Innovation precinct, the first outside China, was unveiled last year with Malcolm Turnbull present at the signing ceremony in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, alongside the Chinese premier, Li Keqiang.

Since 1988 the Torch program has brought businesses together with universities and researchers inside China to create high-tech startups. The Chinese government says it has accounted for 11% of the country’s GDP. This $100m deal included an initial $30m from eight Chinese companies to support Australian research.

Since then 29 Chinese partners and one Indian one – Adani Solar, a subsidiary of the resources giant – have signed on to the UNSW Torch project. They include at least seven firms working in industries with dual use military potential such as aerospace, GPS navigation, underwater cameras and nanotechnology. The research is not funded directly by the Chinese government but by the companies themselves.

One of the companies participating in the scheme is Huawei Technologies, the Chinese firm banned from participating in Australia’s national broadband network in 2013 on security grounds, based on the advice of Asio – the Australian national security agency. Earlier this year, it was reported that Nick Warner, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service’s director general warned the Solomon Islands against using Huawei to connect its under-sea cable.

On its Torch website designed to draw in potential investors, the university highlights research with explicitly military applications such as unmanned military vehicles.

Richard Suttmeier, an American expert on China’s science policy and emeritus professor at the University of Oregon, raised US concerns that Beijing’s aggressive decades-long technology acquisition drive was allowing China to quietly supersede other countries in certain fields.

On the UNSW cooperation he said: “One can’t help wondering about a Faustian bargain quality to the program. Increasingly China is able to dangle very, very attractive incentives for cooperation. International partners can reap benefits in the short run but may lose out in the longer run if they lack farsighted strategies.”

Clive Hamilton, professor of public ethics at Charles Sturt University, said: “I think the Torch program will make UNSW in effect a client university of the People’s Republic of China in its science and technology areas, and more broadly because PRC and its agencies will have a huge amount of sway over university decision-making.”

Rory Medcalf, the head of the Australian National University’s national security college, has expressed concern that research with potential for military use could bypass existing controls.

“The fundamental question to ask is if there is [a] prospect of technology discoveries being shared that could potentially give China a military advantage in the region over, for example, US and its allies, and therefore potentially Australia.

“This is not necessarily about issues of war or conflict, which nobody wants. But it’s about issues like surveillance, detection, submarine activity; areas where our militaries are, to be honest, competing with one another day to day.”

Brian Boyle, UNSW’s deputy vice-chancellor (enterprise), championed the Torch project as “delivering a return on investment for Australia through our outstanding and competitive research base”.

He said all potential partners had been scrutinised by an external company, ensuring collaborators “meet the level of requirements we would expect, in terms of company performance and behaviour”.

Questioned on Huawei’s participation, he said that the university had undertaken the appropriate due diligence and adhered to defence export controls.

“We believe they are a good company to be working with,” Boyle said, adding the two were collaborating on touchscreen technology.

He described concerns about any possible use of this technology for military purposes as a “very long bow to draw”.

The UNSW website hosts Torch-branded “research capability statements” that showcase the university’s research strengths to potential Chinese investors. At least three trumpet specific military applications, including “impact and blast-resistant construction materials” developed at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

Another project concerning high-speed, high-precision self-driving vehicles listed a potential application as being “unmanned military vehicles”.

Asked why UNSW was touting military research to potential Chinese investors, Boyle said they were for “general purpose use”. When asked why they were on the Torch website, he replied, “That’s our key customer base at the moment.”

“We follow the rules,” he added.

UNSW has been explicit in its motivations for seeking alternatives to Australian government funding. “We didn’t want to keep going back, cap in hand, to Canberra asking for more,” Ian Jacobs, its vice chancellor, wrote in an in an article for the Australian newspaper last year. “Instead, we went to China.”

In a separate opinion piece, for the Australian Financial Review, Jacobs wrote: “To join China’s innovation train, we need to move quickly and take on a degree of risk.”

Boyle said: “We believe that in taking these financial and technological risks we are performing the best service to Australian society.”

The university has also been upfront about the central role played by China’s Ministry of Science and Technology in the Torch enterprise. Chinese officials have handpicked the first group of companies participating in the scheme. The university offers Chinese companies looking to invest in the precinct rent-free office space and tuition scholarships for employees to undertake PhDs.

The flagship project under Torch is a $20m collaboration between UNSW engineer Dr Sean Li and Hangzhou Cables, which helped fund a $10m laboratory on the university’s Randwick campus, as well as a second collaborative lab in Hangzhou alongside the company’s production facilities where prototypes of the new graphene electricity transmission cables can be produced faster than in Australia. It took just three months to open the lab after the negotiations were finalised.

For Li, who joined UNSW 13 years ago, this collaboration marks a huge positive shift in university culture. “Now we are doing something to convert fundamental research to practical application,” he said, describing how he has filed nine patents in the past two years.

“This is a big change for myself, and for the university. That’s why the Torch precinct is a very, very rapid development.”

The partners have set up a joint venture, with UNSW taking a 20% stake to Hangzhou Cable’s 80%, and royalties shared equally between the two sides. Li confirmed that the new technology had been subject to checks under defence trade control legislation.

The 150 Torch precincts inside China play a key role in Beijing’s full-throttle mission to become a technology power. Its ambition – articulated under the banner “Made In China 2025” – is to have 70% of the country’s manufacturing supply chain fed by Chinese companies by 2025. China’s broader science policy, described as “technonationalism”, feeds its voracious appetite for cutting-edge technologies.

Promoting its Torch collaboration, the university declares its potential to play a powerful role in China’s development. “The rise of a great power needs more. It needs UNSW,” is the sign-off line in the university’s official Torch promotional video.

Jacobs has also explicitly linked Torch with the “Made in China 2025” policy, and China’s desire to become a world technology and science powerhouse by 2049. “To get there will require not only an immense national effort by China but also strong and enduring international collaborations,” he told a gala event last year. “That’s where we come in.”

One vocal supporter is Dr John Saunders of the Linden Group, infrastructure specialists with close Chinese ties, who believes such schemes should receive more support. “I think the UNSW needs to broaden this. I think it needs much bigger commitment from federal government, and I certainly think it can be – not replicated – but can become a model elsewhere in Australia.”

Turnbull declined to comment on the Torch concerns, instead referring to a statement from the Department of Education and Training: “The Australian government is supportive of innovative ideas, which grow Australian society and develop our reputation as a partner of choice internationally.”

UNSW is not the only Australian institution wooing Chinese Torch officials. In May, a 20-strong Torch delegation from China visited Griffith University’s Gold Coast campus as part of an exploratory tour of south-east Queensland. That came two months after Queensland minister Kate Jones met Torch representatives in China to discuss promoting the Gold Coast “health and knowledge precinct” as a future Torch project.

Nor is it the only university wooing Chinese money. The University of Technology Sydney (UTS) has launched a centre for advanced science and technology research, funded by the state-owned China Electronics Group Corporation (CETC), a deal worth $20m over five years. Meanwhile, the University of Melbourne and RMIT are opening an incubation space providing Chinese funding of $80m in partnership with the City of Melbourne and the Australian China Association of Scientists and Entrepreneurs.

Critics of the collaboration fear that, in the rush to cash in on Chinese funding, some institutions may have failed to recognise the potential risks.

“On one hand, the universities have been forced into a position where they’re just out busking for money,” says Stephen Fitzgerald, the first Australian ambassador to China in the early 1970s. “On the other hand we have a government that seems to be incapable of taking a serious, considered, long-term, strategic view of our relations with China.”

Peter Jennings, executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said. “Universities have never met a dollar they didn’t like … [They] have been frankly a bit wilfully blind to the implications of getting too financially dependent on China.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest

A central concern of many experts is the potential military application of technologies being developed in partnership with foreign companies. They caution that emerging technologies are often so complicated that scientists can’t forecast how their work will be used, including whether it might have so-called “dual use” civilian/military applications. The monitoring of the development and use of cutting-edge technologies is a particularly thorny issue, given the level of specialisation required to understand the implications of such research, and the complexities of attempting to control constantly evolving technologies.

“These are highlighting some of the real challenges of the 21st century, when what is military research and what is civilian research don’t really have meaningful distinctions,” says Dr Margaret Kosal, from the Sam Nunn school of international affairsat Georgia Institute of Technology, who conducts research on potential proliferation threats of nanotechnology.

Medcalf said: “The problem is with some of these technologies, potential for dual use may be there but we won’t know the full extent of the dual use or the full extent of the risk until after the technologies have been shared. In other words, having an export control and licensing arrangement, as we’ve done in the 20th century, for military and dual use technologies, will be too late.”

The mood in Washington has recently shifted towards fear that China’s unabashed focus on innovation, combined with its traditional disregard for intellectual property protection, will inexorably lead to Beijing superseding the US as the world’s leading technology power.

Suttmeier, who briefed President Barack Obama’s council of advisers on science and technology, said: “I think the US has woken up to the sophistication of Chinese technology development strategies, and to the overall thrust of Chinese industrial policies which lie behind a lot of these questions.”

Attempts to contact the Chinese embassy in Canberra and the Ministry of Science and Technology in Beijing for comment did not yield a response.

Plans for phase two of the Torch precinct include the redevelopment of 100,000 square metres at UNSW’s Randwick campus, a project which Yuan Wang, the Torch project manager, said would require capital investment in the order of $1bn. She said potential future areas of joint research could include artificial intelligence and telecommunications.

“I would like to see us helping to work with China on some of its major issues that we also share,” Boyle said. “That is an ageing population, it’s also in terms of energy.” He touted the benefits of future expansion as benefiting “both Australian, Chinese and indeed global industries,” as well as boosting jobs in NSW.

• This article also appears at the Citizen. Anders Furze is a journalist at the Citizen, based at the University of Melbourne. Louisa Lim is a senior lecturer at the centre for advancing journalism at the University of Melbourne, and a former NPR and BBC correspondent based in Beijing. Lim is also the author of The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!