Fang Fang: Author vilified for Wuhan Diary speaks out a year on

BBC World Service, Hong Kong

Jan 19 2021

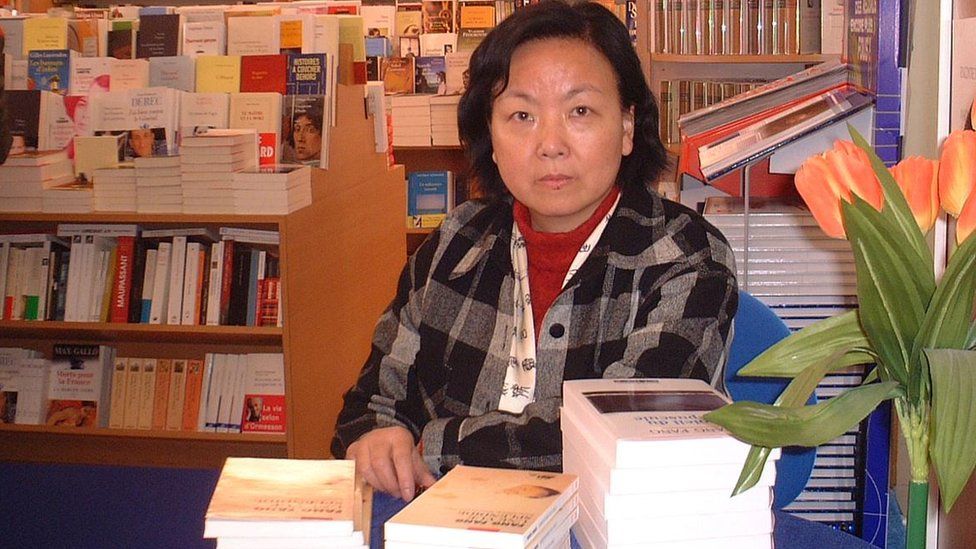

She has faced a nationalist backlash for her diaries documenting life in Wuhan in the early days of the coronavirus outbreak, but Chinese author Fang Fang she says she will not be silenced.

"When facing a catastrophe, it's vital to voice your opinion and give your advice," she told BBC Chinese in a rare email interview with international media.

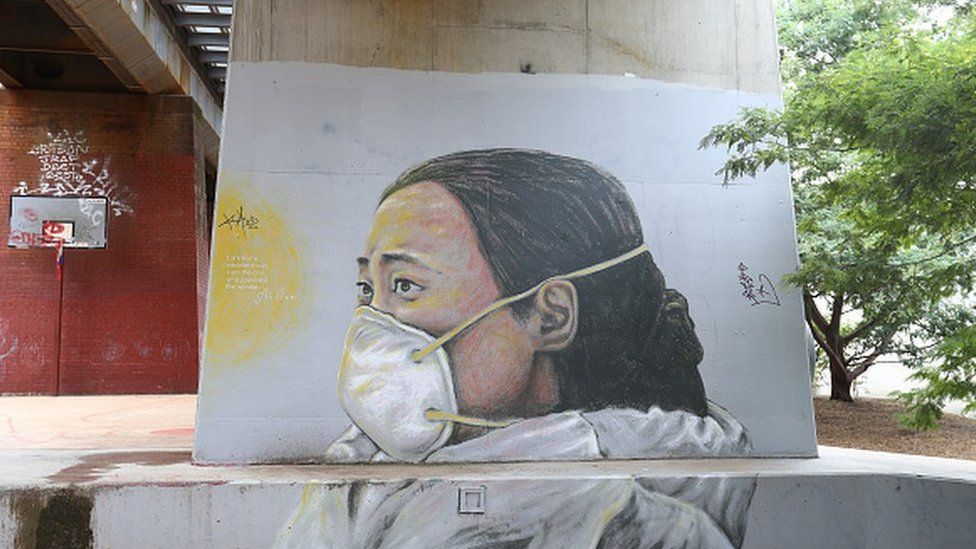

In late January, when Wuhan became the first place in the world to enter a state of complete lockdown, many of the city's 11 million residents found solace in reading Fang Fang's online diaries. They also provided a revealing glimpse into the city where the virus first emerged.

The 65-year-old's daily posts on her Weibo account, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, chronicled life living alone with her dog during the lockdown, as well as what she described as the dark side of the authority's response.

They were initially well-received, but later provoked a wave of criticism from those who saw her efforts as unpatriotic.

As part of the BBC 100 Women season, Fang Fang told the BBC why, despite the condemnation, she does not regret speaking out.

'Vivid narrative'

Fang Fang says that she wrote the diaries as part of a process that helped her to "channel her mind" and reflect on what was happening during lockdown.

She captured what it was like to be isolated from the rest of the world; the collective pain and sadness of witnessing the loss of life; and the anger at local officials for what she views as their mishandling of the crisis.

At first, her online diary was praised domestically, with state media the China News Service describing her posts as inspiring, "with vivid narrative, real emotions and a straightforward style".

But the reaction significantly shifted when they gained international attention and the criticism reached fever pitch when news emerged that her diaries would be translated into English and picked up by US publisher HarperCollins.

"Because of the 60 diary entries I wrote during the pandemic… I am seen as the enemy by the authorities," she said.

Chinese media outlets, she says, have been ordered not to publish any of her articles. And her books, including new works and reprints, have been shunned by Chinese publishers.

"For a writer, it's a very, very cruel thing," she told the BBC.

"Maybe it's because I have expressed more sympathy for ordinary people than applauding the government. I didn't flatter or praise the government, so I am guilty."

Storm of abuse

Fang Fang says that the backlash was not restricted to official disapproval.

She says she has received tens of thousands of abusive messages, including death threats. On social media she has been labelled a traitor, accused of conspiring with the West to attack the Chinese state, with some even suggesting she was paid by the American intelligence agency, the CIA, to write the diaries.

Fang Fang says she was surprised and confused by the viciousness of the attacks.

"It's very difficult for me to understand their hatred of me. My records are objective and mild," she says.

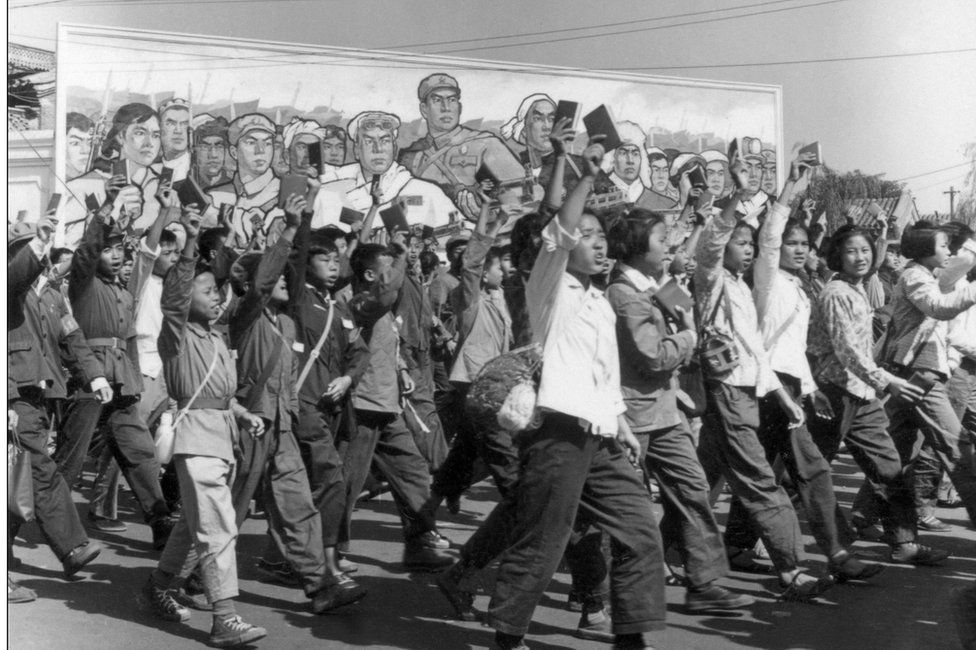

The attacks she says remind her of the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, a period of violent mob rule which led to the purging of intellectuals and "class enemies", including people with ties to the West.

China is sensitive about its image abroad, and Fang Fang's diaries came during a time when the country was under immense international pressure for alleged cover-ups.

Fang Kecheng, a journalism professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says the attacks on Fang Fang follow a pattern of online nationalism. "Nationalism has become the mainstream on the Chinese internet in recent years, and liberalism has been marginalised. Nationalist internet users are very active, and they have become nationalist trolls," says Prof Fang.

He says online nationalism has been "implicitly endorsed" by Chinese authorities because it could help boost the support for the government - but it could also backfire if this gets radical.

"Words specifically used during the Cultural Revolution, such as 'class struggle' and 'dictatorship of the proletariat' have re-emerged. It means that China's reforms are on their way to failure and regression," she says.

Necessity of lockdown

After watching the coronavirus spread to almost every corner of the world, Fang Fang says China's decision to impose a 76-day lockdown in Wuhan was the right one, a stance reflected in her diary entries at the time.

"The lockdown was a heavy price we paid in exchange for now being able to live freely in Wuhan without the virus," she says.

Wuhan has reported no local cases since May. It does not count asymptomatic cases.

"If severe measures had not been adopted, the situation in Wuhan would have further spiralled out of control. So I expressed support for almost all disease control measures."

And Fang Fang says other countries can learn from aspects of China's approach.

"During the outbreak, all gatherings were banned, everyone was required to wear a mask, and a health QR code was needed to enter a housing complex. I think all these very good measures helped China control the virus."

Lessons learnt

But China's ultimate success in containing the virus domestically does not negate, she argues, the need to investigate the initial handling of the outbreak by the authorities.

"There has been no thorough investigation into the reasons why it took so long to tackle the outbreak," Fang Fang says.

She questions why at first authorities said the virus was "preventable and controllable".

But Fang Fang says the world, not just China, needs to learn from the pandemic.

"It is human ignorance and arrogance that let the virus spread so widely and for so long."

Professor Michael Berry, who translated her diaries into English, believes "her resilience is rooted in the knowledge that she is doing the right thing".

"She is not a dissident, she is not calling for the overthrow of the government; she is an individual that documented what she saw, felt, and experienced during the Wuhan lockdown," he said.

But in doing that he argues, she does explore bigger questions "not only the handling of the pandemic, but about what kind of society Chinese citizens want to create for themselves".

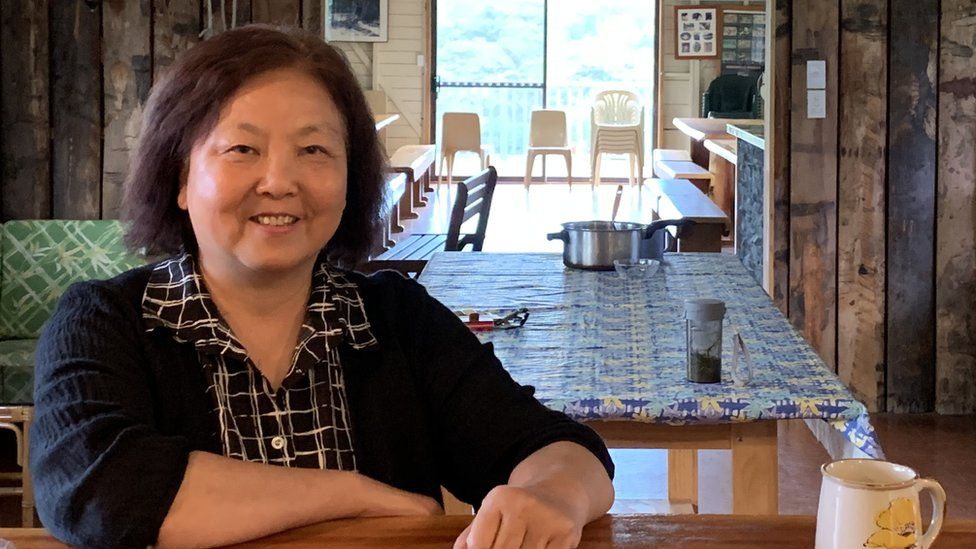

In Wuhan, Fang Fang's personal life was dealt a blow when her 16-year-old dog, a constant companion throughout the lockdown, died in April. But she is resilient.

She is still writing in the hope that her works will once again be published in her own country, and says she has no regrets.

"I definitely will not make compromises, and there's no need to stay silent."

Additional reporting by Lara Owen

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year, and tells their stories. Follow us on Instagram and Facebook and join the conversation, using#BBC100Women.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!