The Sneaky Chinese Illicit Drug Industry in America

Chinese Chemical Company, Senior Leaders Indicted for Fentanyl Manufacturing, Distribution

LOS ANGELES — A joint investigation resulted in charges for Hubei Aoks Bio-Tech Co. Ltd., a chemical company based in Wuhan, China, its director and three senior employees in U.S. federal court Nov. 7, for allegedly selling fentanyl precursor chemicals and xylazine — known as “tranq” — globally.

This Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Los Angeles investigation was worked collaboratively with Southern California Drug Task Force, with significant contribution from DEA, Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the California Department of Justice.

“HSI is dedicated to disrupting the flow of fentanyl, and the precursor chemicals necessary to produce this poison, entering our communities,” said HSI Los Angeles Special Agent in Charge Eddy Wang. “Today’s announcement of charges is a warning to those who seek to profit from the sales of these precursor chemicals used to manufacture fentanyl and other manufactured narcotics.”

The company is charged with one count of conspiracy to manufacture and distribute fentanyl and to distribute listed chemicals for the manufacture of fentanyl, one count of conspiracy to distribute listed chemicals for importation to the United States, two counts of distribution of listed chemicals for importation, two counts of distribution of listed chemicals for manufacture into controlled substances, and seven counts of introduction of misbranded drugs into interstate commerce.

Also charged in the recently unsealed indictment are:

- Xuening Gao, 38, Hubei Aoks’ sole director, who is charged with two conspiracy counts;

- Guangzhao Gao, 36, the operator of Hubei Aoks’ cryptocurrency wallets used for fentanyl precursor sales and who is charged with a total of six felonies, including four distribution-related counts;

- Yajing Li, 30, a Hubei Aoks sales manager who also is charged with six felonies, including conspiracy and distribution of a listed chemical; and

- A fifth defendant who uses the alias “Jessie Lee,” a Hubei Aoks sales manager charged with two conspiracy counts.

The People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of Public Security took law enforcement action against the defendants by dissolving the indicted Chinese company and arresting the four indicted Chinese national subjects. The Chinese Ministry of Public Security is further coordinating with the Department of Justice on the investigation.

“Companies such as Hubei Aoks disguise their illicit activities as legitimate business operations yet continue to knowingly contribute to the fentanyl crisis in the United States,” said Special Agent in Charge Tyler Hatcher, IRS Criminal Investigation, Los Angeles Field Office. “This indictment highlights our commitment to partnering with other law enforcement agencies to combat this epidemic. IRS Criminal Investigation is the best in the world at following the money, whether it be within traditional banking systems or via cryptocurrency platforms, and we will tirelessly pursue the necessary evidence to bring suspects to justice.”

According to the indictment, for more than a decade, Xuening Gao and Guangzhou Gao have sold controlled substances and precursor chemicals, including fentanyl precursors, to customers throughout the United States. Both men are linked to chemical companies operating in China, including one that sold fentanyl and acetyl-fentanyl that was imported into the United States as far back as 2015.

Hubei Aoks exported chemicals to at least 100 countries, including the United States, and advertised online and through various social media platforms. Hubei Aoks sales representatives tailored their precursor recommendations depending on the customer’s geographical market and would suggest alternative chemicals if one was not available. Hubei Aoks claimed that fentanyl precursors were most popular in Mexico and sold them in 25-kilogram fiber drums, each of which can produce 10 million fentanyl pills. Representatives claimed that their profit on precursors sales to Mexico was worth the risk.

From at least November 2016 to November 2023, Hubei Aoks sold and imported to the United States 11 kilograms of fentanyl precursors, capable of producing millions of fentanyl pills, along with two kilograms of xylazine, a tranquilizer, used by veterinarians to sedate cattle, horses, and other large animals. As part of an undercover investigation, the chemicals were falsely imported into the United States as furniture parts, vases, makeup, and other items.

“This enforcement action reflects CBP whole-of-government effort to anticipate, identify, mitigate, and disrupt illicit synthetic drug producers, suppliers, and traffickers,” said Cheryl M. Davies, CBP Director of Field Operations in Los Angeles. “This comprehensive approach brings the unique, formidable, and wide-ranging capabilities and authorities of CBP to bear on the illicit synthetic drug trade and build capacity and collaboration with our partners – domestic and international – to ensure the safety of the American public.”

“The shipment of dangerous substances like fentanyl precursor chemicals through the U.S. Mail helps to fuel a pandemic that affects many Americans today,” said Inspector in Charge of the United States Postal Inspection Service in Los Angeles, Matt Shields. “Precursor chemicals are extremely dangerous substances and pose a serious threat to the health and well-being of our society. The U.S. Postal Inspection Service stands proudly with our federal law enforcement partners as we continue to fight to protect the U.S. Postal Service and Americans from illegal and dangerous substances.”

The U.S. can do more to stop the illicit drug trade

In 2024, there were 80,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States. While this is down significantly from 100,000 in 2023, it still is a staggering loss. In addition to taking American lives, the drug crisis poses a serious national security threat. The Chinese Communist Party uses drug warfare as a way to spread disaster in countries that have a military advantage like the U.S, according to a playbook authored by two former senior Chinese military officials.

One of the techniques used to funnel money into the U.S. by Mexican drug cartels is known as the black market peso exchange, a system used by Colombian cartels during the 1970s and 80s drug trade. With the proceeds of their illegal sales stuck in the United States, Colombian kingpins had to convert the funds in the country from the U.S. dollar to the Colombian peso. The result was a deceptively simple network of various U.S. bank accounts, shell companies, and money brokers capable of sending the money to Colombia as goods to be sold and converted to pesos.

Despite its apparent simplicity, the black market peso exchange persists, used by Mexican cartels and Chinese nationals seeking to circumvent China’s strict capital control laws. The process is as follows:

- The cartel sells drugs in the U.S. and is paid in U.S. dollars.

- This “dirty money” is bought by a broker and sold to a Chinese national, who pays for the dollars in Chinese yuan.

- The broker then uses the yuan to buy Chinese goods and send them to Mexico.

- The goods are sold in Mexico and converted into pesos before returning to the cartels.

This process allows Chinese nationals to circumvent restrictions on how much money they can send out of China and enables cartels to convert the money from their drug sales into pesos without repercussions.

Anti-money laundering laws that were used to prevent such activity originated in the 1970s. After the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) of 1970 was signed into law, banks began to submit reports to the Department of the Treasury on suspicious activity and high-value cash deposits. However, these laws have seen minor updates since then.

To protect against the threat of illegal drugs entering the U.S., Washington must protect the integrity of its financial institutions.

Banks already must comply with reporting requirements. However, the volume of these reports far exceeds the capacity of the Department of Treasury. In 2023, banks filed nearly five million Suspicious Activity Reports and 23 million Currency Transaction Reports. The Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has approximately 300 employees–an amount far too small to examine all documentation.

To streamline the process, financial institutions should know the most helpful information to submit. Banks likely have little clarity on what information is useful, resulting in excessive and unnecessary reporting.

Treasury’s FinCEN Exchange – a public-private information sharing partnership between law enforcement, FinCEN, and financial institutions – can be used to clarify what data is most pertinent to send.

The U.S. government should also put to better use Section 6201 of the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020, which requires the attorney general to notify the secretary of the Treasury what bank information is most useful for investigations, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of anti-money laundering efforts. Based on a 2024 report from the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Justice continues to face challenges sharing the information that is most effective in leading to arrests.

Furthermore, the BSA E-Filing System, the platform banks use to submit these reports to the Treasury Department, should categorize the suspicious activity the bank is reporting. Doing so will help eliminate the lack of clarity surrounding the drug trade.

Lastly, the U.S. government should collect the beneficial ownership information for domestic companies to determine who financially benefits from them. Without knowing the benefactors, law enforcement will face challenges in determining the criminals behind these networks.

Policymakers should be concerned that the method being used by drug traffickers to launder money in the U.S. has remained in use for decades. Old policies and protocols have failed to stop the flow of drug money in the U.S. Without action, this illicit money will likely continue to flow through our country’s financial institutions. Stopping the drug crisis is a priority. Policymakers must treat it as such.

How does fentanyl get into the US?

Reuters

ReutersHe has also threatened higher tariffs on Mexican imports but delayed enforcement to allow for negotiations to take place.

How serious is the fentanyl crisis in the US?

Fentanyl is a synthetic drug manufactured from a combination of chemicals. US regulators approved it for use in medical settings as a pain reliever in the 1960s, but it has since become the main drug responsible for opioid overdose deaths in the US.

More than 48,000 Americans died in 2024 after taking drug mixtures containing fentanyl, according to the US Centres for Disease Control (DCD).

The US has long accused Chinese corporations of knowingly supplying the chemical components to gangs who trade in them. The White House has also accused Canada and Mexico of failing to prevent criminal gangs from smuggling fentanyl into the US.

It is frequently mixed with other illicit drugs, leading many users to be unaware that the substances they are consuming contain fentanyl.

As little as a two milligram dose of fentanyl - roughly the size of a pencil tip - can be fatal.

Over the past decade, the global fentanyl supply chain has expanded, making it harder for law enforcement and policymakers to control.

China is the primary source of the precursor chemicals used to produce fentanyl.

Canada's role in the fentanyl trade

President Trump has accused Canada - alongside Mexico - of allowing "vast numbers of people to come in and fentanyl to come in" to the US.

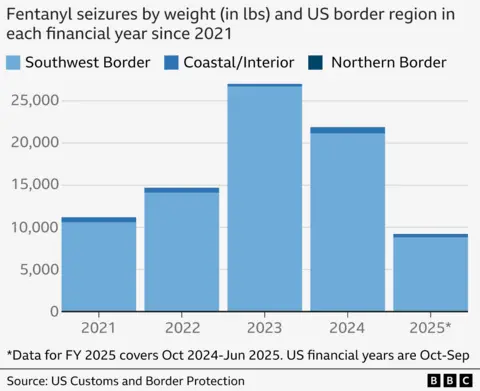

According to data from the US Customs and Border Patrol, only about 0.8% of all seizures of fentanyl entering the US so far this year were made at the Canadian border. Almost all of the rest is confiscated at the US border with Mexico.

But in January, Canada's financial intelligence agency reported that organised criminal groups in Canada are increasingly involved in the production of fentanyl by importing chemicals used to make it and lab equipment from China.

The trade in fentanyl takes place in both directions.

In the first 10 months of 2024, the Canadian border service reported seizing 10.8lb (4.9kg) of fentanyl entering from the US, while US Border Patrol intercepted 32.1lb (14.6kg) of fentanyl coming from Canada.

In December, the country pledged C$1.3bn ($900m; £700m) for combating fentanyl and enhancing border security.

And in February, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the appointment Kevin Brosseau, as Canada's fentanyl czar.

Fentanyl enters the US via Mexico

Since last October, 9,200 lb (4,182kg) of fentanyl have been seized in the US, according to figures published by US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP).

Almost all (96%) was intercepted at the south-west border with Mexico. Less than 1% was seized across the northern US border with Canada. The remainder was from sea routes or other US checkpoints.

According to the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), Mexican criminal organisations - including the Sinaloa Cartel - play a key role in producing and delivering fentanyl, methamphetamine and other illicit drugs into the US.

The chemicals used to make fentanyl are sourced from China by traffickers and turned into the finished product in labs in Mexico before being smuggled into the US.

According to the DEA, the Sinaloa Cartel uses a variety of tactics to conceal shipments coming into Mexico, such as hiding the chemicals among legitimate commercial goods, mislabelling the containers, using front companies, and shipping through third party countries.

The Trump administration has accused the Mexican government of colluding with the drug cartels. Mexico's President Sheinbaum says the claims are "slander."

In December, shortly after Trump had threatened Mexico with tariffs, the country's security forces announced their largest ever seizure of fentanyl - equivalent to around 20 million doses.

In response to the threat of tariffs from the US, in February the Mexican government launched Operation Northern Border, deploying 10,000 national guard troops along the US-Mexico border.

China is the source of fentanyl chemicals

In 2019, China classified fentanyl as a controlled narcotic and later added some of the chemicals used to make it to the list.

Despite this, the trade in other chemicals involved in the manufacturing of fentanyl - some of which can have legitimate purposes - remain uncontrolled, as those involved in the trade find new ways to evade the law.

A review of several US indictments, which include details of undercover agents communicating with Chinese manufacturers, suggests that some chemical companies in China have been selling chemicals - including controlled ones - in the knowledge that they are intended to make fentanyl.

- US, Mexico, Canada - who got what from tariff stand-off?

- Trump sows uncertainty - and Xi Jinping sees an opportunity

- Trump's tariffs hit China hard before - this time, it's ready

Dozens of indictments reviewed by BBC Verify detail instances where Chinese manufacturers have provided instructions on how to make fentanyl from products they sell, through encrypted platforms and cryptocurrency payments.

"So you have these massive loopholes where criminals engage in selling legal products, but they knowingly sell them to criminal entities," says Vanda Felbab-Brown, senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institute.

In a statement, China said it had some of the strictest drugs laws in the world and had conducted joint operations with the US in the past.

"The US needs to view and solve its own fentanyl issue," it said.

In a US indictment from January 2025, two chemical companies in India were charged with supplying the chemicals used to make fentanyl to the US and Mexico.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!