Poor Attitudes towards the less fortunate: Conceptions of Poverty among the Rich and Powerful in China

June 2019

In primary school, nearly every Chinese child reads Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Match Girl’, a short story that is supposed to foster empathy for the poor. Chinese children also read Dostoevsky’s Poor Folk, a novel that explains that poor people are noble, kind, and compassionate, always willing to help others despite their tremendous difficulties in life. While these stories are meant to teach the Chinese youth to be empathetic, respectful, and kind to the less fortunate, in practice these ideas have frequently remained secondary to social status and one’s position in the social hierarchy.

Chinese society is no doubt saturated with status-consciousness. In such a context, what kinds of attitudes do people situated on the top rung of the social ladder hold toward people on the bottom rung? After all, ‘poverty alleviation’ is one of the government’s chief policy priorities and charity work is also taking place on a large scale in the public sphere (see Snape’s op-ed in the present issue).

With this question in mind, in 2018 I conducted a series of interviews with a couple dozen rich people around the country, asking about their views of, and perceived responsibility for, the poorer segments of society. The latest Hurun report on Chinese wealth, released in November 2018, provides a relatively clear definition of the rich in mainland China. In it, the ‘rich or high-net-worth families’ (高净值家庭) are described as those with investable assets of more than six million yuan. In 2018, China had about 3.2 million such high-net-worth families, with an average of three members each. This means that, in total, there were nearly ten million rich people in China, less than 1 percent of the population. With this frame of reference in mind, those people I interviewed belonged to the top 1 percent, and were involved in businesses as diverse as restaurants, investment companies, and real estate.

Voices from the New Rich

The ways in which the rich discussed the poor was shocking. Of particular surprise was the way the rich repeated themes found in the Party propaganda. Many of my questions focussed on the draconian campaigns of mass evictions of migrant workers in Beijing in late 2017 (Li et al. 2019). Some of them knew about the eviction campaign, and some had heard about it for the first time from me.

One of my interviewees was a so-called fu’erdai (富二代)—a second-generation rich person—who was educated for several years in the United States and is now running a restaurant and several investment companies at the same time. Well informed about the eviction campaign, he thought that the official media should not have called these migrant workers ‘low-end population’ (低端人口), but rather ‘low-end employees’ (低端产业从业人员). He believed that the government should not have evicted the migrant workers in the middle of winter, but he did agree that it was necessary to drive them away. In his opinion, Beijing had now reached a developmental stage in which this type of worker would no longer be needed. From his point of view, this kind of eviction campaign was an unavoidable side effect of city development, and some changes were necessary to secure further progress. From this perspective the impoverishment of the migrant workers was a natural, and unsolvable, side effect of development.

Another fu’erdai I spoke with had taken over his father’s business after coming back from Canada, where he had stayed for nearly ten years. He saw himself as a an ‘inter-disciplinary talent’ (复合型人才) belonging to the elite class (精英阶层). He was fiercely class conscious and believed that the elite class consisted of people possessing a sense of responsibility for making transformative changes in today’s Chinese society. In commenting on the evictions in Beijing, he compared the poor to a tumour on society: ‘It does not help to treat a tumour by taking medicine only. It takes surgery to take out the tumour and then heal it. What is unbearable for the society is that some people become like “rice bugs” (米虫) [a much-hated pest in China].’ This man told me that the poor are people ‘who have no social responsibility and sacrificial spirit, and that they are lazy hedonists (吃喝玩乐), acting like destructive pests and taking away profit from the society.’

Another respondent—a self-made successful businessman in his early fifties—also commented on the ‘low-end population’. He thought the evictions were legitimate since Beijing did not need these migrants any longer. He was very much in line with the decision of evicting the migrants even in the middle of winter, assuming that they must have been lazing around without doing any proper work and having a negative impact on society.

A fourth interviewee—a rugs-to-riches businessman in his mid-fifties—thought eviction meant progress. He did not deem the evictions as an extreme campaign, but as a necessary way of pushing through good policies. In his words: ‘It is of no use to discuss things: only extreme methods will get things done because the population of China is too huge.’ This comment made me think of Robert Moses (1888–1981), an American city planner and official regulator famous for his brutal plans for transforming New York City, especially the Bronx area. One of the most polarising figures in the history of urban development in the United States, he is described vividly in Marshall Berman’s All That Is Solid Melts into Air. One of Moses’s favourite slogans was: ‘You cannot make an omelette without breaking eggs.’

On a related note, one young and successful businessman in his early thirties showed the least interest in charity among all the interviewees. He did not have any feeling for charity work and he told me that to help ‘the handicapped’ (残疾人) was illusory and disconnected from reality (虚无缥缈). Asked to comment on the ‘low-end population’, he answered: ‘I have my own logical understanding them. As a Chinese idiom says: “Those who are pitiful must be hateful” (可怜之人必有可恨之处). You reap what you sow. If you don’t work hard, poverty will naturally come down on you.’ In the end, he told me that he always voluntarily filtered information about the poor, as he did not like reading this kind of news.

One interviewee used to practice as a dentist, but had now turned to business, running several companies. He had a very positive take on the poverty reduction programme promoted by the government. He pointed out what he thought to be the central problem of poverty: ‘Poverty usually is a matter of having the wrong mindset. The poor cannot be helped unless they strive to change their mindset.’ He basically believed that financial poverty is a less serious problem than a ‘poverty of the mind’. Throughout my interviews I found this tendency to emphasise mind over reality as a widespread pattern among the rich in today’s China.

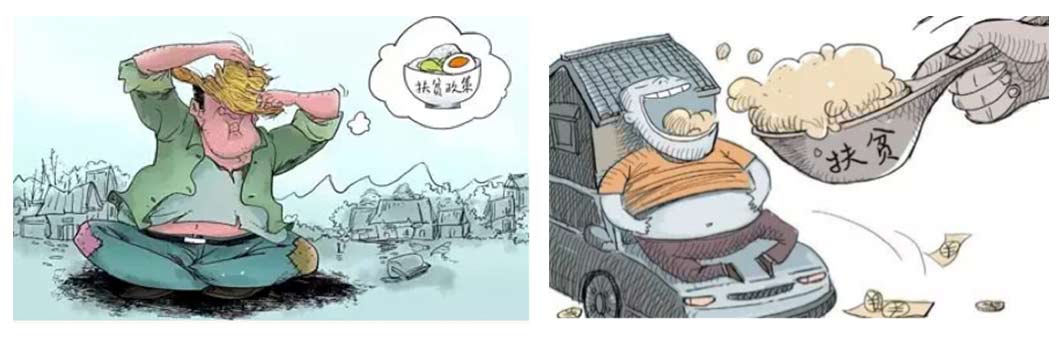

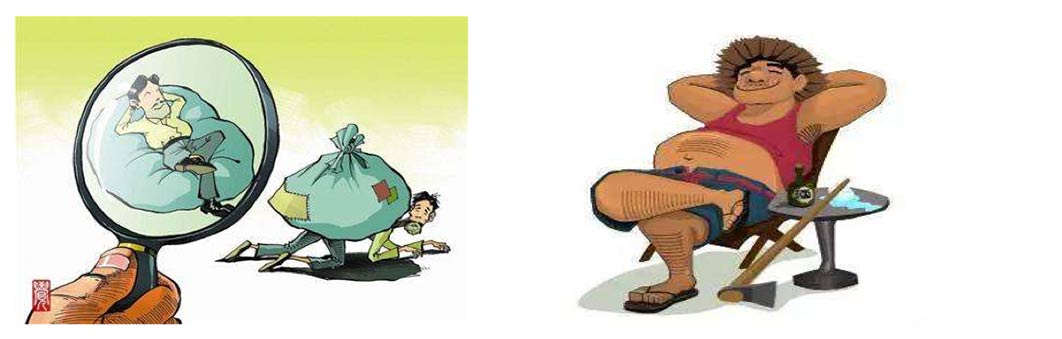

Parroting Party Propaganda

Why do many rich people in contemporary China see the issue of poverty as a problem of mindset? Are they in denial so as to maintain their privileged position? Or are they just short of proper education on social issues? It is hard to say, but an analysis of Party propaganda provides some preliminary insights. Since at least 2005, official propaganda has systematically depicted the poor as ‘sluggards’ or ‘lazybones’ (懒汉). The People’s Daily and Xinhua popularised this concept, making ugly caricatures about the poor peasants who just feed on government funds without making the slightest effort to lift themselves out of poverty. Following their lead, local newspapers across China scrambled to jump on the bandwagon, in what has clearly become an overwhelming, undeclared campaign from above to shape popular opinions of the poor.

Inequality in a society is generally measured by the Gini coefficient—a statistical measure of income/wealth distribution. China has travelled from the most equal—albeit very poor—society in the world in 1978 with a Gini of 0.18, to one of the most unequal societies today, with official statistics showing an income Gini of just under 0.5 and a wealth Gini of 0.73. World Bank estimates place China among the two or three most unequal societies in the world (AFP 2012). In such a context, the rich are powerful not only financially, but also normatively, acting as norm-setters and influencing how people from other social classes behave and react to social issues. In this light, the victim-blaming attitudes common among the financial elite seem to have effectively blinded a significant segment of Chinese society from seeing the root causes of poverty. This has resulted in the demonisation of those people situated at the bottom of the social pyramid.

China is not alone in fostering this kind of anti-poor discourse. To cite an example, in 1965 Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan from the American Department of Labor published a report entitled ‘The Negro Family’—a document that has come to be seen as a blatant attack on poor African Americans, giving birth to the expression ‘blaming the poor’. Whether it is in the United States or China, the real problem is that blaming the ‘lazy poor’ allows the structural causes of poverty to be systematically neglected. Today it seems that the ‘Chinese Dream’ has become strangely entangled in some of the worst ideological biases of the old ‘American Dream’. This is ironic considering ‘common prosperity’ (共同繁荣) is one of the most important ‘core values’ of the Socialist Core Values Campaign (社会主义核心价者观), which lies at the centre of the ‘Chinese Dream’. In a significant departure from socialist values, the politics of poverty meant to achieve common prosperity described in this campaign centres on the idea of ‘cultivating the lazy man’ (养懒汉). With the legacy of the Moynihan report now paradoxically living on as a ‘socialist core value’ in China, the poor have simply been rebranded as ‘lazy’, and Andersen and Dostoevsky’s stories have once again been reduced to fairy tales.

How crazy rich Asians in Vancouver

go into business

When the tap that pours almost unlimited funds gets turned off, changes have to be made. For some second-generation rich, that means real estate and winemaking

Chelsea Jiang is young, Asian and ultra-rich. And she is part of a growing demographic in Vancouver, Canada, that shares a similarly privileged lifestyle punctuated by lavish parties, luxury cars, international travel and designer clothes.

“Crazy rich” Asian Vancouverites are so common they’re almost a cliché. They have money beyond imagination and live a flashy jet-set life that would be largely frowned upon back in China. Vancouver, however, is the perfect backdrop for this new generation of wealthy Asians, eager to flaunt their purchasing prowess.

In Vancouver, Asian taste for luxury fashion meets local hipster look20 Jul 2018

For Jiang, 28, this opulent lifestyle landed her a starring role in the YouTube series Ultra Rich Asian Girls, a reality TV web series featuring the daughters of affluent Chinese Canadians living in Vancouver.

For two seasons, Chelsea allowed cameras to follow her while she shopped and travelled around the world, recording phone calls, gossip and a number of altercations. Viewers got a voyeuristic glimpse into this rarefied world of extraordinary spending and the pressures that come from managing such a high-maintenance lifestyle.

Like many second-generation rich kids living in Vancouver, Chelsea and her cast mates fuelled their credit cards via generous family allowances, which have been reported to be as high as C$30,000 (US$23,200) per month. Typically, this money flows into bank accounts while they’re in school and university, single and footloose. The wealth seems infinite.

Until one day, the allowance stops.

For Jiang, after the show ended, she got married, had a baby and got divorced. And she lost her family allowance.

Without a trace of betrayal or entitlement, she said during a recent interview, “Why would I want money to support my own family? I wouldn't feel proud spending my parents’ money.” However, she has since moved back in with her parents, who help raise her young son. She is also considerably more cautious talking about her finances, perhaps a lesson learned from her days of over-sharing during filming of the show.

“I'm a bitch,” she quickly acknowledges when I mention I’d been bingeing on episodes of Ultra Rich Asian Girls in preparation for the interview. She is not wrong. Ultra Rich was deliberately modelled after the US reality TV franchise The Real Housewives, which is infamous for its catfights, salacious storylines and similarly privileged social lives revolving around luxury shopping, tropical holidays and the upkeep of palatial homes. On these shows, “the bitch” is a mandatory fixture and the one audiences love to hate – and it’s always easier to hate those who have it all without seemingly having earned any of it.

Speaking to her, however, Jiang seems grounded and intelligent (she has a bachelor’s degree in maths and economics). It is a curious departure from her edited personality on the show, which often portrayed her as impatient and judgemental, cementing her role as an instigator of drama.

Given her reach on social media now (she has almost 69,000 followers on Instagram alone) and loyal fan bases around the world, her new-found caution is wise. Without the steady flow of cash she once had, she now has a better appreciation not just for the cost of luxury when funds are not limitless, but also for how her shopping sprees looked on the show.

That is not to say this former party girl is suffering in any way. Jiang has since started a new career in one of Vancouver’s hottest commodities, real estate, purchasing pre-sale apartments and flipping them.

And while she questions the definition of “ultra rich”, inferring that she never was – let alone now – she is certainly living quite comfortably, by any definition.

For most people, moving back in with their parents is seen as a step back. Chelsea and her son, however, are happily ensconced in her parents’ newly renovated four-bedroom heritage home in the stylish west side neighbourhood of Kerrisdale, where single-family homes start at C$4.5 million. It’s the perfect place to park her Range Rover Sport.

Jiang’s parents are happy to have them, and, luckily, to babysit. That same week, Jiang was getting ready to depart for her annual two-month child-free holiday. Last year she went to France (hated Paris, loved Avignon) and Morocco. This year she is going to China, then Singapore (where she has a massive fan base), and then a week at the Shangri-La hotel in the Maldives.

When asked if she spoils her son, she quickly says no. While she does have a nanny and plans on enrolling him in private school, she does not want him to grow up a slave to labels and says his wardrobe is full of modest Gap clothing.

“So, no Baby Burberry?” I ask.

“Oh. Well, yes, Baby Burberry, of course. And Fendi. But the rest is all Gap.”

To further show her new “thrifty” shopping ways, she showed me a picture of an Alexander McQueen deconstructed embroidered silver metallic leather jacket that she recently bought.

Only five of these jackets were available in Canada and she got hers at a large discount despite its straight-from-the-runway status.

Canadian retailer Holt Renfrew offers its top-tier preferred customers a discreet discount and Jiang was able to negotiate an even heavier cut that brought the price down from C$19,000 to less than C$9,000.

We meet again a few days later at her friend’s birthday party in West Vancouver. The house is in possibly one of the most exclusive neighbourhoods in the city, located on an incline with a stunning view of the city, Stanley Park and the jewel-blue waters surrounding it all.

The 6,700-square-foot (622-square-metre) home belongs to 40-year-old birthday girl Amy Zhang. Zhang spent C$1 million renovating this C$4 million property a few years ago to make it an even more spectacular backdrop for the parties she loves to host.

Unlike Jiang, Zhang is effervescently candid and well-established in a very successful career.

She recently sold her China-based education consulting business and is now transitioning into early retirement.

Like Jiang, Zhang was also getting ready to travel later that week.

Before the party I sat down for an interview with Zhang, who was dressed in a stunning, graphic floral pyjama set by Dolce & Gabbana in accordance with the party’s “sexy pyjamas” dress code. She said that after the party she was travelling to New York as a guest of Fendi to preview a new handbag.

Being courted by luxury brands is nothing new for Zhang, who easily spends C$200,000 a year just on designer clothing (excluding handbags, shoes and jewellery).

But she was only able to start accepting these invitations last year when she sold her business and finally had the time to travel for pleasure. Last year she went to Paris with Dior, Sicily with Dolce & Gabbana, and Milan with Fendi.

These trips typically include a business class plane ticket, room in a luxury hotel and car service.

Zhang is delightfully open about her wealth and how she enjoys spending it, clearly proud of her self-earned riches.

For the past 18 years her company, ReallyLife, matched Chinese students with Canadian and American secondary schools and universities, and flourished during a time when the new generation of Chinese millionaires were establishing their affluence.

The conflation of rising socio-economic means with extremely high educational standards in China meant Zhang’s business skyrocketed as parents sought to find educational alternatives abroad for their children.

A quick tour of Zhang’s bedroom and en suite reveals racks of beautiful clothes, stacks of luxury handbags – an endless parade of Birkins next to Kellys next to Peekaboos – and so many shoes that they spill out of her wardrobe, line one wall of her bedroom three rows deep, and continue on into her bathroom.

There’s everything from Louboutin and Jimmy Choo to Prada and Alexander McQueen – and of course there are her new five-inch sparkling Rene Caovilla stilettos that she is wearing with her pyjamas.

Later that evening, changed into her second outfit – a delicate black lace ensemble by La Perla (shoes by Louboutin) – Zhang introduced me to a number of her guests, a happy, pyjama-clad group made up of clearly very wealthy people. Introductions included a whirlwind of choice professions – a vineyard here, horses there, real estate everywhere.

This group of second-generation wealthy Chinese could soon evolve from its “crazy rich” label and rebrand itself as the business-savvy generation, set to make their own fortunes. And futures.

Inside the world of China’s ultra rich

Kevin K Li, director of reality show Ultra Rich Asian Girls, speaks to Al Jazeera about China’s wealthiest 1 percent.

!['People hungered to know more about who was buying the exotic supercars, exclusive handbags and multimillion-dollar properties,' says Li [Steve Chao/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/3b7601102855422996ec595e8101be83_18.jpeg?quality=80)

!['There's so much misunderstanding and misinformation about Chinese Canadians,' says Kevin Li [Steve Chao/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/4e7f5dc144224a07bd1f557f2bd60def_18.jpeg?quality=80)

!['The girls on my show ... break down traditional stereotypes of Chinese women,' says Kevin Li [Steve Chao/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ec9e7d9e7f0d451ba121163a2fc09074_6.jpeg?quality=80)

![The show's creator, Vancouver-born Chinese-Canadian Kevin K Li, left, and Desmond, right [Steve Chao/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/33b8f22bc5204c89aea0b4b4734c4db5_18.jpeg?quality=80)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!