MONTREAL, Jan. 23 — The narrow stone building on Victoria Square here has an unusual dark green door with prominent brass handles and hinges. But no signs on its exterior or anywhere in the marble lobby behind it indicate that it is the headquarters of the Power Corporation of Canada, one of the country’s largest financial services companies and Quebec’s pre-eminent newspaper publisher.

Given that the Desmarais family, which controls Power, has a penchant for avoiding public attention, it is not surprising that the company is relatively unknown in the United States. That may change soon since Power is now negotiating with the Marsh & McLennan Companies to acquire its Putnam Investments Mutual Fund unit for an estimated $3.9 billion.

With Putnam, Power would be getting a money management business that has struggled as investors have fled its mutual funds since a trading scandal in 2003. At the end of last year, Putnam had $192 billion in assets under management — less than half of what it had in 2000. But Power has an enviable track record, becoming Canada’s dominant mutual fund business.

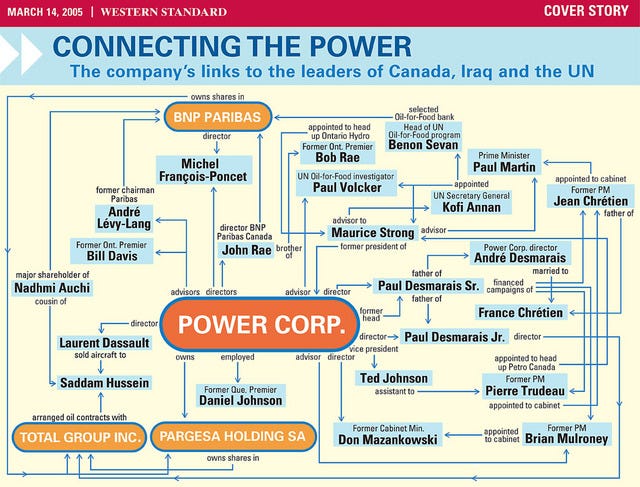

A deal would only add to the already oversize reputation back home of Paul Desmarais and his sons Paul Jr. and André, who became the company’s co-chief executives just over 10 years ago. It is a reputation that goes beyond business. For nearly four decades, the Desmaraises have also been closely linked to several Canadian prime ministers, provincial premiers and other prominent politicians.

“They are in a class all by themselves,” said Jean-François Lisée, the director of the Center for International Studies and Research at the University of Montreal. “There’s the Desmaraises, then there’s everyone else.” Under Mr. Desmarais and his sons, Power has been a long-term investor rather than an operating company. Its operating units — including London Life Insurance, Canada Life Financial and the Investors Group mutual funds — maintain separate headquarters in other cities and are, in many cases, led by managers whose tenure with the companies is measured in decades.

Under Mr. Desmarais and his sons, Power has been a long-term investor rather than an operating company. Its operating units — including London Life Insurance, Canada Life Financial and the Investors Group mutual funds — maintain separate headquarters in other cities and are, in many cases, led by managers whose tenure with the companies is measured in decades.

The approach has been effective. When Canada’s five national banks were allowed into the brokerage business in 1987, many assumed the banks’ immense retail branch networks would allow them to dominate the market for mutual funds. Twenty years later, however, IGM Financial, the holding company for Power’s investment fund companies, is the leading Canadian operator with about 106 billion Canadian dollars ($89.70 billion United States) under management.

Power Corporation said that neither Mr. Desmarais nor his sons were available for an interview.

Paul Desmarais, who turned 80 this month, began as an outsider. He grew up in a French-speaking enclave in Sudbury, Ontario, a mining town where English ruled. At the same time, not being from Quebec set him apart from French-speaking business leaders in Montreal.

In 1951, Mr. Desmarais dropped out of law school to revive a bankrupt short-line railroad and local bus line in Sudbury that was founded by one of his grandfathers.

After sorting out the family operation, Mr. Desmarais discovered leveraged buyouts and reverse takeovers. Within nine years, he was in Montreal as the owner of Provincial Transport, the biggest intercity bus operator in Ontario and Quebec.

A bitter strike by the company’s drivers during the summer of 1962 curbed Provincial’s cash flow and prompted a strategic shift.

“We needed to diversity as far away from the bus business as possible if I was going to be able to have more stable growth and profitability and keep the bankers away from my door,” Mr. Desmarais recalled in a 1998 speech.

Using a cash hoard of 12 million Canadian dollars, Mr. Desmarais bought control of Imperial Life in 1963. His deal-making quickly picked up pace.

Roy Thomson, the newspaper magnate who was on his way to building Canada’s largest family fortune, suggested Mr. Desmarais buy La Presse, Montreal’s leading broadsheet newspaper. (Mr. Thomson did not want to buy a paper published in a language he could not read.) Mr. Desmarais borrowed the 15 million Canadian dollars for that deal over a lunch break partly because Mr. Thomson, conveniently, was also a Royal Bank of Canada director.

Roy Thomson, the newspaper magnate who was on his way to building Canada’s largest family fortune, suggested Mr. Desmarais buy La Presse, Montreal’s leading broadsheet newspaper. (Mr. Thomson did not want to buy a paper published in a language he could not read.) Mr. Desmarais borrowed the 15 million Canadian dollars for that deal over a lunch break partly because Mr. Thomson, conveniently, was also a Royal Bank of Canada director.

A person close to the Desmarais family, who after consulting them agreed to speak only if he was not identified, said that Mr. Desmarais sustained his leveraged deal-making by quickly paying down debt. That, he added, and the fact that Mr. Desmarais “is a person of immense charm.”

It was gaining control of Power in 1968, however, that solidified Mr. Desmarais’s position both in Quebec and across Canada.

As its name suggests, Power originally was an electric utility holding company. But by 1963, governments across Canada had expropriated all of its utility assets, leaving the company with cash reserves it used to become a conglomerate whose scope has over time narrowed to focus on financial services and publishing. [Shares of Power have more than tripled since March 2000, closing on Thursday on the Toronto Stock Exchange at 35.41 Canadian dollars. ]

Running as a parallel investment universe to Power, is the family’s 50 percent stake, along with the financier Albert Frère of Belgium, in the parent company of Groupe Bruxelles Lambert. André Desmarais was significantly involved in its 2001 acquisition of a 25 percent stake in Bertelsmann, the German media company, and the recent sale of that position for 4.5 billion euros.

The family, which is a strong supporter of Canadian federalism, has generally kept its hands off the editorial pages of La Presse. André Desmarais is the paper’s chairman and president; the editor, whom the family appoints, is always a supporter of a united Canada. But the paper’s star columnist, Pierre Foglia, is a prominent advocate of a separate Quebec.

“The paper is a home for very diverse voices,” said Mr. Lisée, a Washington correspondent for La Presse during the 1980’s who later was a major strategist for the separatist movement.

One issue, however, sometimes provokes questions about the Desmarais clan. For four decades Paul Desmarais or his sons have often enjoyed close ties to politicians of all varieties, even including separatist leaders in Quebec.

“Nobody comes close to them in terms of sheer power,” said Pierre Duhamel, the former publisher of Quebec’s leading business magazine who now writes a business blog for L’actualité, a general interest magazine. “They understood very early that you have to be in the know.”

Critics occasionally charge that the family’s political connections give it unfair advantages.

The man close to the family bristled at that idea. As he sees it, Paul Desmarais became politically active in late 1960’s somewhat out of personal interest but largely because of the rise of Quebec separatism at the time and the terrorist acts that followed in 1970.

And the family connections, he added, were often coincidental. André married France Chrétien long before it was obvious her father, Jean, would become prime minister. Paul Martin, another former Liberal prime minister, was already a Power executive when Paul Desmarais bought the company. Brian Mulroney, a long-serving Conservative prime minister, was Power’s outside labor lawyer well before he entered politics.

“We live in a village in Canada, and there are a lot of circumstances which come together which make it appear as if there’s some great manipulation,” the man close to the family said. “These are the coincidences of life. It might be more notorious than substantial.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!