Once branded spies, Chinese tech trio settles in Canada after immigration officials back down

A single rogue officer in Canada’s Hong Kong consulate is believed responsible for unsubstantiated and explosive espionage accusations against ex-employees of telecoms giant Huawei, that have now been retracted

PUBLISHED : Wednesday, 11 January, 2017

Three ex-employees of Chinese tech giant Huawei, who were accused of espionage by Canadian authorities during their immigration applications, have now been granted permanent residency after officials backed down on the unproven and explosive claims, the South China Morning Post has learned.

Jean-Francois Harvey, whose Harvey Law Group acted on behalf of the mainland Chinese trio, said the now-withdrawn accusations appeared to have been the work of a single officer in the Canadian consulate-general’s office in Hong Kong.

Harvey said an identification code on correspondence proved that the same case officer dealt with all three clients, who have settled in Canada in the past four months.

They were “definitely not” spies, said the lawyer.

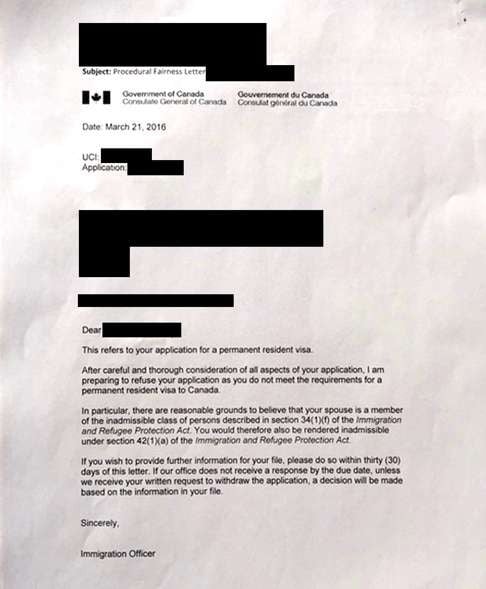

The SCMP reported last May that two of the would-be immigrants had been informed by Canada’s immigration department that their applications for permanent residency were going to be rejected.

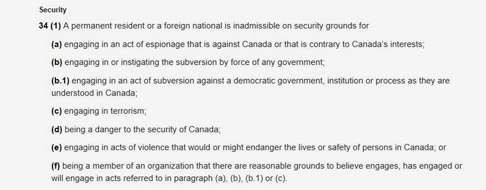

“[There] are reasonable grounds to believe that you are a member of the inadmissible class of persons described in section 34(1)(f) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act,” read a letter to one of the then-employees of Huawei. That refers to people who belong to an organisation engaged in espionage, government subversion or terrorism. A second applicant was told the same in relation to their spouse, who was employed by Huawei at the time.

The third case was only recently disclosed to the SCMP by Harvey. All three have quit the company, said Harvey.

Huawei, the world’s third-biggest smartphone maker and a major provider of global telecoms infrastructure, has long been cited by the United States as a Chinese espionage risk, but Harvey’s clients were believed to have been the first individuals singled out by any foreign government in such a way.

Huawei has repeatedly denied involvement in espionage.

Harvey said that in challenging the accusations, the trio signed detailed declarations, affirming that they were not spies.

I cannot even imagine a supervisor at the Canadian consulate-general in Hong Kong approving such a thing. This was not a ... a ‘management decision’

“They [Canadian immigration authorities] just gave up after each of them signed an affidavit, saying that they were never involved in anything like that, that they have never done any spying or anything that was a threat to Canada in any way, and that was it,” Harvey said.

“We received the medical form a few weeks later, and they got their visas.”

The SCMP has obtained correspondence sent by immigration authorities to two of the immigrants that bears the same two-letter, five-digit code; Harvey said he could not share any correspondence involving his clients, but confirmed that his copies carried the same code and said that it designated their case officer. Harvey said the third client also received correspondence with the same code, indicating it too came from the same officer.

“This officer probably just typed ‘Huawei’ into Google, saw the previous allegations, which were never proved, and just went for it,” said Harvey, whose Hong Kong-based practice focuses on business immigration worldwide.

“I cannot even imagine a supervisor at the Canadian consulate-general in Hong Kong approving such a thing. This was not a group thing. It was not a ‘management decision’, that’s for sure.”

Harvey said individual case officers had “quite strong discretionary powers” and “they can sometimes apply the rules as they see fit.”

In 2012, a US House intelligence committee concluded Huawei was a threat to national security. The firm has been barred from bidding on US and Australian broadband projects.

But in contrast, the company is deeply involved in Canada’s market, providing network technology and equipment for major wireless operators, such as Bell and Telus.

Harvey said the initial rejections amounted to “accusation by association, probably by a junior officer”. “CIC has a huge workforce, handling hundreds of thousands of applications every year,” he said, referring to Canada’s immigration department by its former acronym. “Not all of them are so competent. There are good and bad.”

Harvey said the clients had all settled in a Canadian maritime province, which he declined to specify, under a provincial nominee programme, an economic stream for skilled workers and businesspeople.

A spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada said that “due to privacy concerns, we cannot comment on specific cases without consent”.

Scott Bradley, Huawei’s vice-president of corporate and government affairs in Canada, said: “This is not a matter that involves Huawei, and we will not comment further.”

Harvey said the three former Huawei employees, whose names the SCMP has agreed not to reveal, held positions that were “relatively low-level”.

Victor Lum, vice-president of Well Trend United, a Beijing-based immigration consultancy that acted on behalf of two of the immigrants, told the SCMP last May that they held positions that “could not be more mundane”. “The only common thread is that they work for Huawei, the largest telecom equipment manufacturer in the world, with over 170,000 employees, and R and D institutes all over the world, including, ironically, Canada,” Lum said at the time.

Lum - who spent 12 years as a Canadian visa officer - said the rejection of immigration applicants on suspicion of espionage was exceedingly rare, and he had only heard of two or three such cases while working for Ottawa.

Neither the US nor Australian governments have provided evidence of spying by Huawei or its staff. Last year, Huawei was given an all-clear in Britain by a board which concluded it posed no national security risk.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!