Look at the oil spilled in the world's 2nd 'Best Place for Wildlife'

Decades of exploration and exploitation has led to severe contamination in the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve in Peru’s Amazon

Walk into one of the many tour agencies in Iquitos, the biggest city in Peru’s Amazon, and you’ll hear many wonderful things about the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve. “Best place to see animals in their natural habitat,” one guide says. “An abundance of parrots, paiche and monkeys, and all kinds of bird species,” cries another.

“Pacaya-Samiria”, as it’s dubbed, extends for just over two million hectares and is the second largest of Peru’s 170 “protected natural areas.” In 2015 USA Today’s travel website 10Best voted it the world’s second “Best Place for Wildlife”, losing out to Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands. “Located near the Amazon headwaters in Peru,” 10Best stated, “the reserve is home to some of the biggest wildlife populations in the Amazon.”

This sense of Pacaya-Samiria’s uniqueness is shared by many - in Iquitos, in Peru’s government, across civil society and internationally, especially since it has been declared a “Ramsar site” and “Wetland of International Importance.” Years before he became the country’s first Environment minister, Antonio Brack Egg, now deceased, called it “one of the most important areas for the reproduction of hydro-biological species in the Amazon” and said it protected various species of flora and fauna at risk of extinction, like giant otters, manatees and monkeys.

Indeed, according to a book co-published in 2014 by the Iquitos-based Fundamazonia, Pacaya-Samiria has 965 plant species, 102 mammal species, 527 bird species, 69 reptile species, 67 amphibian species and 269 fish species, and is “in the epicentre of wild fruit consumption in the Amazon.” Richard Bodmer, Fundamazonia’s president and one of the book’s co-authors, told the Guardian that, in addition to its “very rich aquatic bird species mixed with very rich forest bird species”, as well as its “very high diversity in animal species”, Pacaya-Samiria is “by far the largest fisheries reproduction area in western Amazonia”:

It’s a flooded forest because it is at the confluence of the two major rivers that form the Amazon: the Maranon and the Ucayali. In the flooded season, the fish go into Pacaya-Samiria where there are a lot of food resources - all the debris left on the forest floor, all the fruits which have fallen and all the insects which are hanging onto the trees and leaves. That leads to reproduction. Basically, Pacaya-Samiria becomes an inland sea of 20,000 square kilometres - the largest flooded forest in western Amazonia - full of fish food. When the water goes down, the fish leave and go into the Maranon, Ucayali and Amazon. They move down and out of the reserve as it becomes drier. The whole fisheries of this section of western Amazonia to a large extent depends on Pacaya-Samiria.

No doubt about it, Pacaya-Samiria is a special place, but that only makes this question all the more important to ask: What about the oil operations taking place there? What about the parts of the reserve the tourists and wildlife watchers don’t see? PUINAMUDT, a collective of indigenous federations in Peru’s northern Amazon, states that there are “true lakes of oil, [river] banks abandoned to crude, clots of oil in the water, black roots and sediments, toxic hydrocarbon emissions, and surface water iridescent with oil. The shadow of irresponsible and unpunished oil operations hangs over the entire area.”

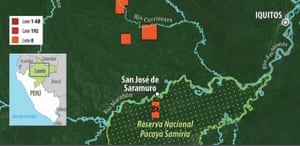

Don’t be misled by Pacaya-Samiria’s “protected natural area” status. Oilcompanies have been there for decades. Operations are currently in the north-central part of the reserve which forms part of a concession called Lot 8, one of the top four most productive oil concessions in the country. In the 1970s it was Peru’s own Petroperu working there, but since 1996 it has been Pluspetrol, initially leading a consortium but since 2003 partnered by the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC).

Contamination and other negative impacts have been reported for decades - by state institutions, by indigenous organisations, by NGOs. Yet complaints and calls for clean-up, improved infrastructure and better practices have gone almost totally unheard. For many years, from the 1970s-onwards, toxic production waters were dumped into the reserve’s rivers and the River Maranon itself, and the pipelines in the reserve are decades-old, rusty, corroded and leaky, according to reports and local people.

In 2013, following the establishment of a government Cross-sector Commission the year before, several ministries entered Pacaya-Samiria to test the water, soil and sediment as part of a wider investigation of the Maranon basin and other rivers in Peru’s northern Amazon. The results were released in January 2014 and led to the Environment Ministry declaring 221,000 hectares of the Maranon basin - including most of the Lot 8 area in Pacaya-Samiria - to be an “environmental emergency” zone. Peru-based NGO Alianza Arkana summarised the investigation results:

Contaminants were detected in water, soil, sediment, and drinking water within and outside of the oil concession 8X operated by Pluspetrol. . . OEFA [within the Environment Ministry] found soils that contained hydrocarbons (TPH), as well as heavy metals such as barium, cadmium, lead, mercury, and arsenic. . . [The] ANA [Agriculture Ministry] examined water and sediment samples from 30 points monitored in the interior of the National Reserve and along the Marañon and Samiria River. They found contaminants such as arsenic, zinc, mercury, and others. Most prominent however is the presence of lead. . . DIGESA [Health Ministry] concluded that none of the monitored communities has access to clean drinking water. . .

What are the impacts of this contamination on the indigenous Kukama Kukamiria people, who consider much of Pacaya-Samiria their territory, and all the plants, trees, fish, wildlife and 1,000s of other people who depend directly or indirectly on the reserve? Who is going to clean it up? How can current and future operations be improved?

10 years ago Peru’s Energy Ministry approved a “Complementary Environmental Plan” (PAC) written by Pluspetrol which identified four contaminated sites in Pacaya-Samiria and listed methods and a detailed chronology to clean them up, but in 2012 OEFA found Pluspetrol had failed to meet its commitments and fined the company almost 30 million nuevo soles (approximately £6 million). Pluspetrol’s response? To refuse to pay the fine and take legal action against OEFA. On 1 June 2015 the Superior Court of Justice in Lima ruled against the company, but Pluspetrol quickly announced that it had appealed and lodged a complaint against the judge involved.

Pluspetrol has even attempted, retroactively, to absolve itself from the PAC. That, the company itself stated, was the basis of its appeal of the 1 June 2015 ruling. Four days after the contaminated sites in Pacaya-Samiria were supposed to have been cleaned up, back in May 2009, the company requested that the Energy Ministry declare the PAC “inapplicable” on the grounds that the proposed methods posed a danger to Pacaya-Samiria and a new plan was required. The Energy Ministry refused. Pluspetrol’s response? To take legal action, this time successfully, following a ruling by the Superior Court of Justice in Lima in 2013.

PUINAMUDT’s Renato Pita Zilbert described the 2013 ruling to the Guardian as “absurd” and “unthinkable” and said it means “nothing will change” in Pacaya-Samiria, where he calls the contamination “terrible.” Lawyers from the Lima-based NGO Institute for the Legal Defence of the Environment and Sustainable Development (IDLADS) were even more scathing, issuing a statement on Pluspetrol’s legal strategy in Lot 8 and another concession which included:

Once upon a time a company proposed a plan to clean up the environmental contamination in its concession, and, with the deadlines unmet, decided to ignore its initial agreement and say that its plan was inapplicable because Mother Nature had already regenerated the area better than it had proposed. . . What would happen in a world where an oil company is legally exonerated from its socio-environmental obligations, and in addition abolishes the state’s capacity to identify environmental liabilities, thereby creating a land without Environmental Law where the company is literally untouchable? Incredibly, that place has a name. It’s called Peru. The company that invented this island of impunity is Pluspetrol Norte.

Some people also accuse Pluspetrol of trying to conceal the contamination. PUINAMUDT has noted how difficult it was for a public prosecutor and various ministries to visit contaminated sites in 2012, and that would also explain, according to Pita Zilbert, the non-native reeds (“totora” in Peru or “typha domingensis” in Latin) which the company has been planting.

“Their effect is evident,” PUINAMUDT has stated. “A carpet of green covers - hides - extensive areas of soil and water permanently black with oil.”

“From the sky it’s going to look all green,” one man, who has lived in the region but didn’t want to be named, told the Guardian, “but below everything’s black.”

Alfonso Lopez, president of the indigenous Kukama Kukamiria organisation ACODECOSPAT, agrees that Pluspetrol has been attempting to hide the contamination. He claimed as such in 2012 and did so again last year, saying ACODECOSPAT’s work to “reveal the contaminated sites concealed by the company” is “part of its constant fight to defend Kukama Kukamiria territory and the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve.”

In November 2015 researchers from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies, and the Erasmus University Rotterdam released a report on contamination in Pacaya-Samiria. Based on a survey of 73 technical reports by public and private institutions analysing 420 water samples and 145 soil samples in the reserve, the report found that concentrations of lead, arsenic, nickel and cadmium in the water exceed legal limits, and also found evidence of contamination by TPHs and oils, which are unregulated. In addition, it found levels of TPHs, barium and lead in the soil exceeding legal limits - with the worst-hit zones near the centre of oil operations in the reserve, called “Bateria 3”, and along the pipeline running north to the River Maranon.

The researchers stated that in recent years Pluspetrol began to “reinject” its toxic production waters into the ground rather than dumping them into the reserve’s rivers, but claimed that “contamination connected to oil activities” has continued.

Pacaya-Samiria is run by SERNANP, within the Environment Ministry. Former head of the reserve, Javier Noriega, told the Guardian the affected zone has “oil everywhere” and is “completely ugly” and acknowledged the pipelines are “very old”, but also said that some have been sabotaged and the worst of the contamination dates back decades. He said that oil operations are just one of “various threats”, including illegal logging, to the reserve.

“What I remember very well is the odour, the constant smell. I think we got headaches from walking the day in hip-deep, contaminated water around Pluspetrol’s base,” one man, who visited the reserve with several Kukama men but preferred to remain anonymous, told the Guardian. “The most impacting stuff we saw, though, was along the pipeline. Around the middle of the 16 km duct leading through and out of the reserve towards the River Maranon we came across a large and pretty fresh crude oil spill. It was about two to three hectares.”

Pluspetrol, Petroperu and CNPC did not respond to requests for comment.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!