Ten Intoxicating Moments in Vancouver History

Launchpad of a nation's war on drugs. Land of drunk driving steamships. And much more.

- Vancouver Was Awesome: A Curious Pictorial History

- Arsenal Pulp Press (2013)

2. The upside of the Great Vancouver Fire? Free booze.

On June 13, 1886, the barely two-month-old City of Vancouver burned to the ground. It was a tragedy; it's estimated more than 20 people lost their lives and thousands lost everything they owned. But it was a baptism by fire, and it spurred the ambitious building of a substantial city.

News of the blaze was carried in newspapers internationally, making it Vancouver's introduction to the world. Money flooded into the city in the form of relief, insurance claims and investment for reconstruction. Within days, new structures were sprouting from the charred landscape.

Not everyone waited for the fire to run its course before making the best of a bad situation. A newspaper article syndicated in the Toronto World and New York Times described the revelry:

"During the confusion which prevailed, when rowdies and roughs saw that every one [sic] was leaving, they entered the saloons which had been left entirely unprotected and commenced drinking. Many a one was seen staggering along the streets with a keg of beer on his shoulder and as many bottles of liquor as he could appropriate," it read.

Another witness described the "rough and wild crowd [that] held revelry... Whiskey casks that had escaped the fire, by being rolled into the water, had been breached and the contents lent their maddening influence to the already over-excited crowd." By the next day, the Victoria Times reported that "the rowdy element prevails at present, but Constable Huntly anticipates no serious trouble."

3. The Vancouver Police Department was formed to save whiskey nearly lost in the Great Fire.

The brand-new City of Vancouver hired John M. Stewart as its lone police officer on May 10, 1886. His only assistant in the first month was John Clough, the one-armed jailer who got the job because he had been such a frequent, but well-behaved, prisoner for public drunkenness. Jackson T. Abray explained to city archivist Major Matthews how he became one of the first officers hired to work under Chief Stewart:

I was sworn in as a constable the day after the Fire of 13 June 1886, sworn in by Mayor MacLean, right out in front by where the Maple Tree had been -- out on the middle of the street. You see, after the fire some barrels of whisky were lying about -- down on the beach. I suppose someone had thrown them out when the fire came along, they lay there, until the next day, when some fellows decided they wanted them, and got them in a boat, and were making off with two or three barrels of whisky in the direction of the Narrows. MacLean came along, and walked up to me right there in the street, and said, 'Here, Abray, you go off after that liquor,' swore me in as constable, and I went after it, and brought it back. I didn't intend to stay on the police force but I did.

Vancouver police historian Joe Swan writes that V.W. Haywood and John McLaren "were appointed under similar circumstances and a number of special constables were also made. So suddenly, Chief Stewart had a police force to lead."

4. The famous wreck of the Beaver was caused by drunk driving.

The Beaver steamship holds the distinction of being the first in the North Pacific. It was built in 1835 and arrived on the West Coast the following year, where it operated for more than half a century, servicing the fur trade and the gold rush, and surveying British Columbia's coastline for the Royal Navy. In its final years, it was bought by locals who converted it into a tugboat for service in the lumber and coal industries.

The ship met its demise on July 26, 1888. The inebriated crew realized it was running low on whiskey and crashed on the rocks below Prospect Point attempting to turn the vessel around. The crew survived, waded out of the water and headed to the Sunnyside Hotel to finish off the night.

For the next four years, the wreck of the Beaver was a Stanley Park landmark, and scavenging the old paddle-steamer became a popular pastime for souvenir hunters. The Beaver was dislodged and submerged by the waves of a passing ship in 1892 and is now a popular scuba diving site, though scavenging is no longer permitted as the wreck has been designated a heritage site.

5. Chinatown opium dens were used to justify the Chinese head tax.

When the Royal Commission to Investigate Chinese and Japanese Immigration came to Vancouver in 1901, the commissioners wanted to see Chinatown opium dens first hand. They hired a photographer and went on a tour led by Detective Wylie, who was supposedly "learned in the ways of the Chinese." The result of the investigation was to raise the head tax on Chinese immigrants from $50 to an exorbitant $500. The World newspaper used the photos to describe the opium dens in detail:

[The commissioners] visited the "dope" dives in the rear of No. 6 Dupont [East Pender] street, which is just around the corner from Carrall, and in the rear of No. 96, as nearly as can be judged from the position of the numberless shacks on the alley. Police supervision is too strict in Vancouver to make it possible to have anything like recognized opium parlors, furnished with swell fittings as can be seen in San Francisco, for instance. But the Chinese have small rooms off their living apartments where they lie in numbers and smoke dope to their hearts content, though the surroundings are not very up to date, even for a dope joint.

6. Canada's 'War on Drugs' began here.

After the September 1907 rampage of the Asiatic Exclusion League through Chinatown and Japantown, the federal government appointed deputy minister of labour and future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to head a commission to investigate losses sustained during the rioting. Two of the largest claims of $600 each came from opium manufacturers. One was submitted by King Fung Co. at 517 Carrall Street, now the parking lot for Jack Chow Insurance. The other claim was for 37 Dupont Street (now East Pender), where Lee Yuen operated an opium factory, probably in the building on the rear of the lot designated 34 Market Alley.

King arrived in Vancouver the month after the riots and dealt with property damage claims in Japantown first, awarding $9,000 to Japanese Vancouverites who suffered losses. He returned the following May and repeated the process for Chinese claims, which cost the Dominion government $27,000. King had some extra time on his hands after his investigation wrapped up, so he took up the Chinatown-based Anti-Opium League on their offer to give him a tour of Vancouver's opium factories. One factory had been operating for 10 years, employed 10 people and grossed $180,000 in 1907 alone, with a net profit of $20,000. The other operator had been at it for 21 years, employed 19 people and grossed between $170,000 and $180,000 in 1907, netting a cool $15,000 for the year.

King learned that there was another opium factory in New Westminster and three or four more in Victoria. But the real shocker was that taxpayer money -- in the form of compensation for lost business -- would be going towards the production of opium, which was being "sold to white people as well as to Chinese and other Orientals" across the country. King raised the issue in his report, which he followed up with another report dealing specifically with opium.

"The Chinese with whom I conversed on the subject," King wrote in his report, "assured me that almost as much opium was sold to white people as to Chinese, and that the habit of opium smoking was making headway, not only among white men and boys, but also among women and girls. I saw evidences of the truth of these statements in my round of visits through some of the opium dens of Vancouver." As a direct result of Mackenzie King's inquiry, Canada's first drug laws were introduced in 1908.

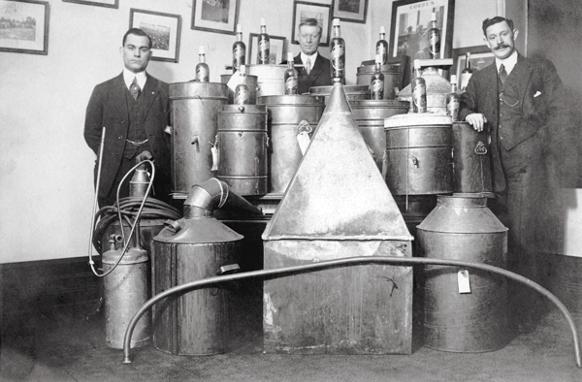

7. Alcohol prohibition was no deterrent for determined Vancouverites.

Temperance advocates spent years pushing for alcohol prohibition in British Columbia, but it was not until the First World War that the political scale tipped in their favour. Along with rationing and other measures on the home front, prohibition was essentially part of British Columbia's war effort, and came into effect in October 1917.

Prohibition did not make Vancouver a temperance town, but neither did it have the infamously disastrous effects it did in American cities such as Chicago. There were so many exemptions and workarounds to the law that getting a drink was not much more difficult than before prohibition. Joe Sheftell, the manager of a vaudeville group visiting Vancouver, explained to a Chicago newspaper the most popular method of obtaining booze in Vancouver: "All you have to do up here is to pay fifty cents for a prescription and [you] get all the liquor you want." Indeed, over 315,000 prescriptions were written in 1919 alone, and some doctors were writing more than 4,000 each month in B.C.

Doctors were not the only ones making a killing off prohibition. Vancouver became a major exporting centre for smuggling booze into the United States, which continued long after B.C. became the first province to repeal prohibition in 1921. Enormous fortunes were made by enterprising brewers-cum-rumrunners such as the Reifel family, whose local legacy includes the Commodore Block on Granville Street. Bootleggers and "blind pigs" (speakeasies) also fared well under prohibition, but not nearly as well as exporters and, as the photo above shows, they were the main targets of the police department's Dry Squad.

8. Vancouver played an important part in popularizing LSD.

One of the more fascinating chapters in Vancouver's long history with mind-altering substances comes from the early days of LSD research in the 1950s. An unexpected but enthusiastic advocate of LSD experimentation was Al Hubbard, an eccentric and enigmatic American millionaire who became the biggest North American supplier of LSD through his Uranium Corporation, whose mailing address was 500 Alexander Street in Vancouver, a skid road rooming house.

Hubbard turned thousands of people on to LSD, including writer Aldous Huxley, the head of Vancouver's Holy Rosary Cathedral and various researchers and clinicians, including Dr. J. Ross MacLean, who teamed up with Hubbard to lead an LSD program at Hollywood Hospital, a private facility in New Westminster that treated alcoholism and psychological disorders. Celebrities, cabinet ministers and others who could afford the program fees were given LSD in an environment controlled and supervised by trained hospital staff who had themselves tried the drug. Staff members included B-movie starlet Mimsy Farmer, futurologist Frank "Dr. Tomorrow" Ogden and activist Sid Tan. While tripping on acid, patients listened to classical music in a room adorned with a reproduction of Dali's Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

The rising popularity of LSD as a recreational drug for hippies led to a moral panic, and the drug was banned. Hollywood Hospital survived until 1975; as for Hubbard himself, his mission as the "Johnny Appleseed of LSD" ate up his fortune, and he returned to the U.S.

9. A drunk Hunter S. Thompson once applied for a job at the Vancouver Sun.

Hunter S. Thompson was a young and still unknown journalist in New York in 1958 when he saw a Time Magazine article describing the fresh direction Jack Scott, the new editor of the Vancouver Sun, was taking the paper. Thompson had not yet seen an issue of the new-and-improved Sun, but thought it sounded like a paper for which he might like to work. He wrote to Scott, offering his services and asking to see a copy: "I stepped into a dung-hole the last time I took a job with a paper I didn't know anything about," Thompson wrote, but "unless it looks totally worthless, I'll let my offer stand."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!