China's drug habit fuels return of the Golden Triangle

AXEL KRONHOLM

AXEL KRONHOLM

By the end of this year Myanmar should have been free of narcotics. Instead, production of opium is soaring and the East Asian country, once part of the fabled Golden Triangle, is the second largest producer in the world. Axel Kronholm investigates why.

Proposing a toast at the end of a successful meeting is not an unusual practice in many parts of the world. A handshake suffices for most people. For others it may involve knocking back a glass of the local hooch.

In Chin state, those attending a village meeting on agricultural development are invited to take a hit of opium.

A rusty tobacco tin is passed round as village elders, farmers and even the staff of a local non-government organisation (NGO) use a toothpick to scoop up a tiny dark, gooey pellet of raw opium - and swallow.

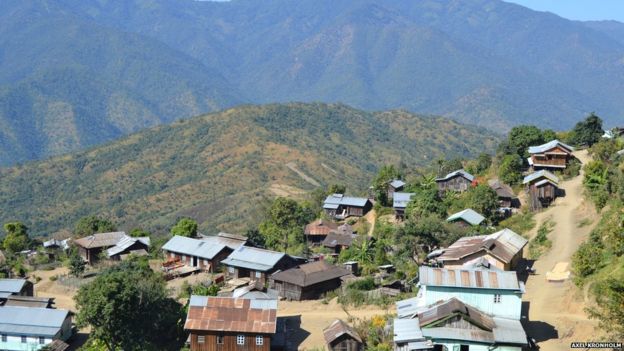

Scattered on the slope of a mountain, Mualpi is a village of 175 households overlooking the Manipur river in north-western Myanmar, also known as Burma.

AXEL KRONHOLM

AXEL KRONHOLM

Small-scale opium cultivation has existed here for a long time. About half of the families in the village are involved in opium farming. The surrounding mountaintops are dotted with light green patches of poppy fields.

It's been used as a medicine to treat diarrhoea, dysentery and other ailments.

But over the last decade commercial poppy production has taken hold. Since 2006 opium production has nearly tripled in Myanmar.

Growing trade

The opium is refined into heroin inside the country and then exported to its neighbours. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Undoc) estimates the market value of last year's total production to be around $340m (£220m).

As a result Myanmar can now lay claim to the dubious honour, after Afghanistan, of being the second largest producer of opium in the world. It now accounts for almost 25% of the world's total production.

Right up until the end of the 20th century, the mountains of Myanmar, which was part of the so-called "Golden Triangle" with neighbouring Laos and Thailand, was the largest supplier of opium. The region was then overtaken by Afghanistan.

Demand from China, but also Australia and Japan, is one factor behind the rise in production in Myanmar over the last decade.

The single biggest driver in this turnaround is the growth of demand in China where Undoc estimates that 70% of the heroin produced in Asia is consumed by more than a million users.

Another part of the puzzle is poverty. Ranked 150 out of 187 countries in the UN's Human Development Report, Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in Asia.

Poverty is particularly grinding in rural areas, with insufficient investment in infrastructure and an underdeveloped agriculture sector.

"Farmers see opium cultivation as a way to secure their income and provide for the family," says Tom Kramer from the Transnational Institute, a Dutch organisation that has reported on the production and trade of drugs in south-east Asia.

"It's also a very useful medicine in areas with limited access to healthcare and other medicines."

AXEL KRONHOM

AXEL KRONHOM

At the village meeting in Mualpi, several farmers said they grew opium. One of them, a man in his late 40s wearing a creased cap and a cheerful grin, says that for most people growing poppy is not a choice, but a necessity.

"We do it to survive," he insists. "The income you get from growing maize or vegetables is very low, and can't compare with opium."

Indeed, growing opium can reward farmers handsomely for relatively little work. The season is short - only four months from planting to harvest - and it's easy to transport the product.

Buyers will travel to opium-growing communities to buy the drugs, while farmers must transport maize or other agricultural products to the market to turn a profit.

"Some buyers will even provide the capital up front for farmers to cultivate the opium," adds Mr Kramer.

AXEL KRONHOLM

AXEL KRONHOLM

But this lucrative business is not without risk. As opium is cheap and readily available in the communities that grow it, addiction has become an issue.

Two hours south of Mualpi, in Tonzang, pastor Philip Suang Kho Thang has come to collect a building permit for a rehabilitation clinic for opium users.

"There is no help available," the pastor says, as his trembling hands hold up photographs of seemingly unconscious and intoxicated youngsters.

"It's sad to see how the youth is dragged down into this," he adds. "Old people suffer too, as their children stop providing for them and instead just smoke opium all day."

A carpenter in Tonzang, who used to grow opium, says he stopped because he was worried his children would get hooked.

"I still miss having all that money, especially when someone in our family gets sick or when the kids want a new toy," he says.

"But at least I don't have to worry about my children getting addicted any more."

While demand and poverty fuels the business, conflict and a corrupt and weak state makes it all possible.

Opium is cultivated in remote mountainous areas, where long-term conflict between ethnic rebels and government forces has made law enforcement difficult.

Furthermore, all sides - the army, rebels and militias - each take a poppy tax from the farmers, so have little incentive to end the activity.

Mr Kramer argues that eradication programmes don't work.

"There is no evidence that eradication actually reduces cultivation on a larger scale," he says.

"Globally, opium cultivation levels have only increased in the last 30 or 40 years despite massive efforts of eradication.

"It does however have many negative effects. It feeds corruption and hurts poor communities that are deprived of their main source of income."

After the high, the downer

As cultivation for this season's crop gets under way, further pressure on incomes is already being felt.

At a meeting last week of researchers and opium farmers from across the country, growers said that falling prices and higher labour costs on top of more aggressive "tax" collection has made the business less profitable.

The recent floods and landslides in regions like Chin state have further worsened the outlook.

After failing to meet its own deadline of eradicating poppy production by this year, the government in Myanmar's capital city Naypyidaw has extended it to 2019.

However, observers say, this pledge is as doomed as the last one. With few other sources of income available the farmers' options are very limited.

The opium farmer in Mualpi says it would make the villagers' lives worse if the police managed to destroy their poppies.

"What will we live off then? We would all be in debt and simply have to grow more opium next year to make up for the loss," he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!