Across the Broken Bridge

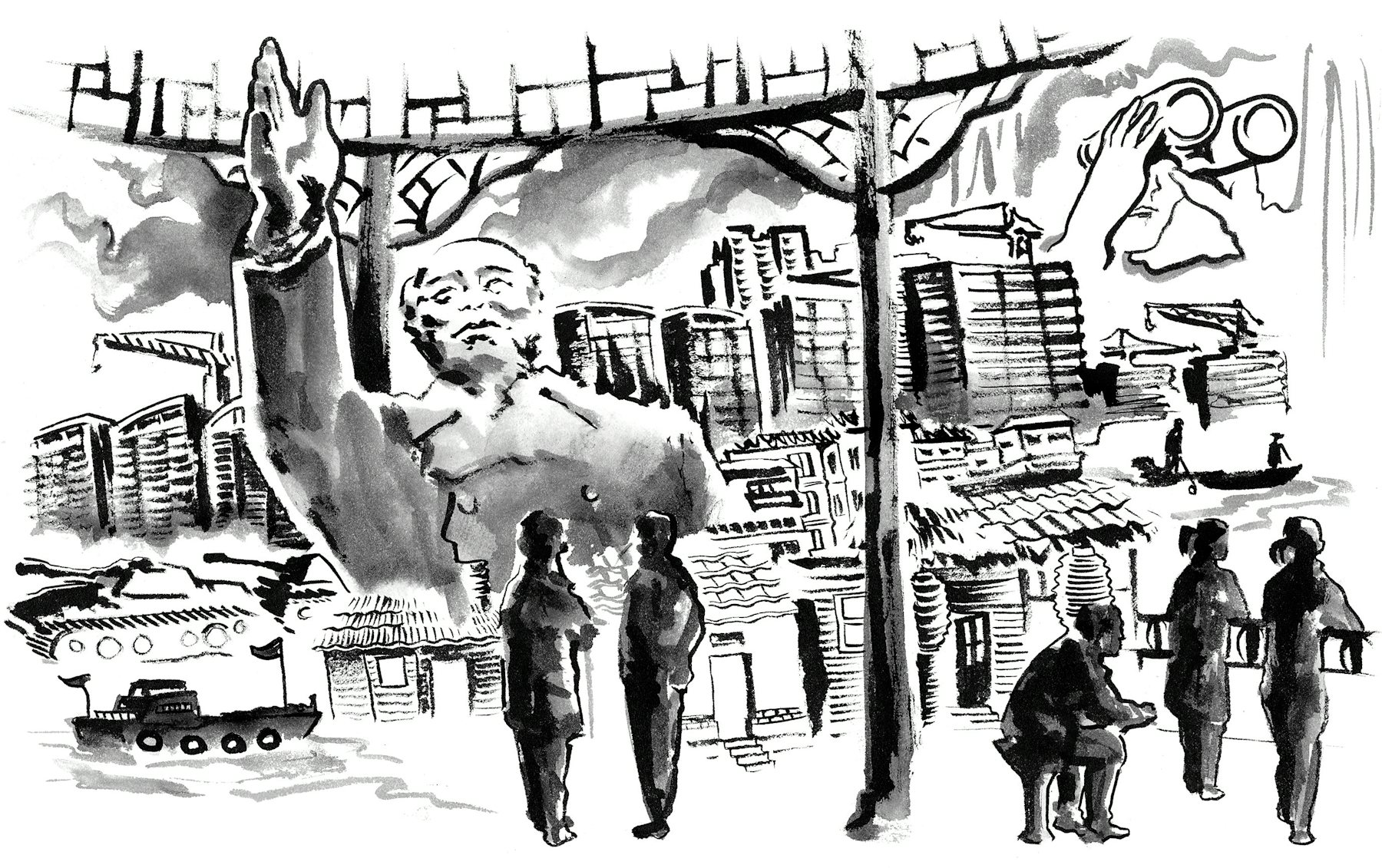

Spies and smugglers in the shadowy underworld of the China-North Korea border.

Haruto-san was a Japanese government official in his mid-forties who spoke fluent Korean. (I have changed Haruto’s name to protect his identity.) I had met him by chance several years earlier in Yanji, another Chinese border town, through a North Korean defector I knew from Seoul. Haruto-san’s job, he claimed, was to determine the whereabouts of Japanese citizens kidnapped by North Koreabetween 1977 and 1983. But the official tally was just 17 victims, and five had already been returned, so I suspected he had other responsibilities. Japan had long been accused of exploiting the issue to heighten tensions in the region so that it could embolden its military. Under the post-World War II pacifist constitution imposed by the United States, Japan could not use military force except under a narrow, and contested, definition of self-defense. Whatever the real nature of his job, mild-mannered Haruto-san, with his black-rimmed glasses and a habit of nodding diligently, looked more like a professor than a government agent. He traveled to this corner of the Chinese border from Tokyo at least once a month.

Sitting before a steaming bowl of soup was a man whom Haruto-san introduced to me as Boss Yu. This title of “Boss” is a strange one; South Korean men sometimes address each other with it, similar to how Americans might use “Mister,” but here it was a way to avoid revealing full names. Instead of saying “hello” in greeting, Yu gestured to the waitress to bring another bowl for me. On the wall was a neon sign that read Pyongyang Dangogi-Jip, which meant the restaurant’s specialty was “sweetmeat,” the term for dog meat in North Korea. It was only eleven o’clock in the morning, too early to eat, I told him—although, in truth, my palate was not generous enough to include such soup. I asked for coffee instead, and the waitress brought a mug of brown, sugary instant. Haruto-san, a follower of Silver Birch spiritualism, who believed that anything with a mother should not be consumed, had only a cup of water before him.

Yu was a small man, about five-foot-six, with beady eyes, a dark complexion, and greasy hair. His heavy eyelids looked swollen, as though he’d either drunk hard the night before or his food had been too salty. He appeared to be slightly older than Haruto-san but was dressed younger, in a nylon tracksuit with a Kappa logo, a shiny silver chain around his neck, and friendship bracelets on his wrist. Listening to him speak, it was hard to guess his origins: South Korean, ethnic Korean from China, ethnic Chinese from North Korea, or North Korean. Of these, only the South Korean accent is distinguishable from the others, and there have been cases of Korean-Chinese people passing themselves off as North Korean refugees to steal humanitarian aid. Despite the similarities, there is a certain something that distinguishes each one, which might be why Haruto-san told me later that while Yu had always said that he was South Korean, he wasn’t entirely convinced.

When I asked Yu where he came from, he shrugged and said in rather nondescript Korean, “Everywhere.” He said that for a man like him, without much schooling, the world was the same anywhere, so he went wherever the winds took him—Hong Kong; Thailand; Japan; and for the past few years, the Chinese towns bordering North Korea. He was a common merchant, he said, but when I asked him what he sold, he demurred. “This and that. Clothes, food, whatever makes money.” The nature of his business with Haruto-san was unclear, and both were silent on the subject.

Once Yu finished his soup and sucked the marrow out of each dog bone, it was time to leave. Our destination was Dandong, three hours away, and Haruto-san had hired a car with a driver who chain-smoked the entire time, although the tobacco smoke did not seem much more toxic than the air in Shenyang, which I was glad to leave behind. I was also relieved to be traveling accompanied, no matter how dubious my present companions.

Dandong had a rather nefarious reputation, shrouded in rumors of danger for those who deal with North Korea. “What do you mean by danger?” I had asked a visiting South Korean minister I met in Seoul earlier in my travels. He had lived in Dandong and helped North Korean defectors in the past. Lowering his voice as though he were used to whispering in fear, he said, “Poison pen. One shot, and you are dead instantly.” Poison pen? Who would use such a thing? But there had been reports of North Korean agents using poison needles hidden inside ballpoint pens as weapons for assassination. “In Dandong, people are never who they say they are. North Korean agents are everywhere. Agents of all kinds are everywhere. You could disappear. Without a trace, with a trace, doesn’t matter, no one would blink an eye.” Our conversation began to sound like dialogue from a John Le Carré novel, which my journey at times resembled.

I wasn’t doing much of anything then, just hanging around the region to fulfill the obligations of a fellowship that had given me a generous travel stipend. I was supposed to interview North Korean defectors, but having already written extensively about them in the past, I felt unable to rouse much enthusiasm for the task. So I traveled the usual escape routes from North Korea through China, which included the Mongolian and Laotian borders, as well as both coastlines of the Korean Peninsula. I kept running into nearly identical characters telling me nearly identical stories about defection.

Vice on HBO, CNN, the BBC, and South Korea’s Channel A had been poking around the region, throwing money around, and a few self-proclaimed local experts had surfaced demanding ridiculous prices to broker meetings with defectors in flight, turning desperate escapes into reality TV. One South Korean expert on defections told me, “All those people are in it for the money: those TV crews following them around for some sensationalistic border crossing documentary, paying off human traffickers. South Koreans are horrible but the worst are the foreign ones because they are clueless, and their ignorance ends up costing lives.”

The whole business was beginning to taste sour, and I kept moving from one border town to another until a message popped up from Haruto-san, who suggested that I join him on his next trip to the region. There was no further explanation of why he was going there, but I knew by now that it was better not to ask too many questions. Shenyang and Dandong, filled with North Korean defectors, contract workers, and government officials, are notorious hubs of sensitive information on North Korea, and I was hoping to learn something new.

Dawn broke early in Dandong, casting light on the smog-filled concrete landscape. My hotel faced the Yalu River, which forms part of the border between China and North Korea. Each room came equipped with an oversized window and a pair of binoculars. The draw for any visitor to Dandong is the view of the forbidden land.

Jutting out from the Chinese side of the river was an iron structure hanging in midair: the Broken Bridge, which was built in 1911 by Japan when it occupied Korea and this part of China. It was partially destroyed by U.S. bombers in 1950, during the Korean War, but its remnants have been kept intact by the Chinese government for tourism. Adjacent to it was another bridge, built in 1943 during the Japanese occupation and later renamed the China-North Korea Friendship Bridge, which allowed car and rail traffic, but no pedestrians. It remains one of the few ways in and out of North Korea.

Across the narrow river, the eerily still facade of Sinuiju, a regional capital in North Korea’s northwestern corner, struck me with a sinking sensation of déjà vu. To my left was a ferris wheel and an abandoned, two-story construction site, and behind it a wall of posters, one of which read: Let’s Arm Ourselves With Socialism And Absolute Watchfulness! Far to the right was an outcropping of buildings; atop one, a sign had been mounted that read Juche (the North Korean self-reliance ideology). In my decade following the trails of North Korea, I was always confronted with these images of monotone buildings and Great Leader-themed slogans. Even in Pyongyang, where I had spent nearly half a year in 2011 undercover,teaching the sons of the country’s elite at the Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, I felt buried beneath the repetitions, every slogan, every building, every story of the Great Leader. Whatever I sought to understand about North Korea was always beyond my grasp; the country’s inherent unknowability was a condition of its survival. And here I was in China, pointing binoculars towards the carefully manufactured sameness of North Korea, yet again hoping for some clue to a better understanding, which most likely did not exist.

The timing for my visit to Dandong was bad—or good, depending on your perspective. North Korea had begun the year with yet another nuclear test, after the U.N. Security Council’s decision to toughen sanctions against the country as a punishment for a previous ballistic missile test. North Korea then shut down the jointly operated Kaesong Inter-Korean Industrial Complex, which housed 123 South Korean companies and 53,000 North Korean workers who brought in $90 million per year in wages, paid directly to the North Korean regime. North Korea then announced the end of the Korean Armistice Agreement, which had been signed in 1953, and threatened a nuclear attack against not only South Korea and Japan but the United States. Yet another American hostage had been sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. (He was an evangelical missionary accused of “hostile acts” against the dprk regime.) The tensions between the two Koreas were at a high boil again, which was nothing new, and yet the intensified sanctions did not seem to affect the flourishing trade between China and North Korea; China accounts for 90 percent of the country’s foreign trade, and Dandong handles about half of that. North Korea’s largest exports—coal, iron ore, and rare earth minerals—flow into Dandong; imports of petroleum, garments, and machinery move the other way. Drugsand weapons cross in both directions.

To kill time, I took a walk on the Broken Bridge, which drew a handful of mostly Chinese tourists. There wasn’t much to do on a bridge that could not be crossed, except that it brought you a few steps closer to North Korea, and I felt oddly defeated walking back and forth. Along the Chinese side of the river, vendors sold trinkets bearing the images of Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung, as well as offering cheap rentals of makeshift hanbok. Groups of Chinese girls tied the apronlike dresses around themselves and posed before cameras with the view of North Korea in the background. There was something sadly humiliating about all this, to witness the beloved national garment reduced to a prop. From one of the vendors’ radios blasted “Bangapseupnida” (“Welcome”), a popular and perky North Korean song:

Countrymen, brothers, let us hold hands,

hot with feelings for the motherland,the unification festivities won’t be far away.Welcome, welcome, welcome, welcome.

The irony of course was that theirs was the most unwelcoming land in the world, forbidden to outsiders, brother or no brother.

Haruto-san said that he was busy with meetings, so I ended up having dinner with Yu almost every night for the next two weeks, always at one of the North Korean restaurants in town. Yu said he was relieved that Haruto-san couldn’t join us since his diet was too restricted. One time, he had screamed after catching a dog’s muzzle floating in a soup they were sharing.

I had introduced myself as an American researcher, which was only partially true, but Yu seemed to consider me with more suspicion than I warranted. He had asked me at dinner at the Pyongyang Koryo restaurant what my identity was, and why I was there. Much like in Shenyang, this state-run establishment employed young North Korean female servers. They were inevitably overly flirtatious, and the food was inevitably overpriced and drenched in MSG. There are believed to be 130 such restaurants around the world, about 100 of them in China. In Yanji, the young women at one of these places are so overworked that after closing they rush over to the nightclub at a nearby hotel for a shift of musical performance and cocktail waitressing with male customers whose Chinese yuan go straight to the North Korean regime. These women are reportedly housed in a dormitory, under constant watch, although with their families back home as hostage, it would be difficult to escape. (A recent incident in which 13 North Koreans defected to South Korea from a similar restaurant is an anomaly.) As the night wore on, the young women brought plastic floral bouquets to the men and urged them to come onstage, where they danced together holding hands in a daisy chain. Yu was on a first-name basis with many of the servers, who smiled at his bawdy jokes in that noncommittal way I have seen female workers in Pyongyang do with foreign men.

I repeated to Yu that I was a mere researcher, which I had hoped would make me seem harmless. There weren’t many women like me hanging around the area, and on several occasions, I had been mistaken for a spy, either for the United States or South Korea. I was afraid that he would clam up if he drew such a conclusion. After a few North Korean Daedonggang beers, Yu began to talk about himself, but always with caution. His specialty, he said, was luxury Japanese goods. He owned a wholesale license in Japan and was able to obtain items at a low cost, which he then sold at retail to a Chinese buyer, who marked them up and sold them to a broker from North Korea. Only the transaction between the Chinese and North Korean was illegal. “I get off scot-free,” he said smugly. When I asked him what kind of goods, he said mostly diamonds, watches, and cosmetics. SK II, the high-end Japanese brand, was in big demand, he said. “Face creams cost $200 a bottle and get sold out each time. Those wives of the party leaders are crazy about Japanese stuff and can never have enough.”

I always looked for a chance to press Yu for details about his business, but when we met it was usually with one of his cronies, including a man called Boss Guk, a tall, bulky 43-year-old who claimed to be ethnic Chinese, born and raised in North Korea. One afternoon, when Guk went off to get us coffee, Yu said to me in a whisper, “Be careful what you say before that guy. He’s not like us. He’s Chinese!” That put a damper on any possibility of an open conversation, and I wondered if it was Yu’s way of discouraging me from asking questions.

Yu said he had a wife and children back in Seoul although he lived mostly in Shenyang. Recently, though, he began renting an apartment in Dandong in a secret location that he used for meetings with VIPs. He cocked his head to suggest the other side of the border, meaning VIPs from North Korea. The building had multiple entrances, so one could enter and exit without being seen. One night after dinner, he invited me over to the apartment. As usual, Boss Guk came along, as did another man I had never met before.

Located at the back of an alley that reeked of fried food was a small two-bedroom apartment, bare except for a mattress on the floor and a beat-up sofa that appeared to have been found on the street. If there were several ways into the building I could not tell, but the one I used was so heavily garbage-strewn and graffiti-covered that it looked like a gateway to a dungeon rather than a residence. I hesitated for a moment before entering. It was not good, of course, for a lone female to walk into a strange apartment in a town like Dandong with a group of smugglers whom she barely knew. But nothing about this region was on the right side of safe. North Korea was murky, through and through, and exploring it had often brought me into yet murkier situations. Yu’s tiny living room opened onto a kitchen area with a stove and a sink. Ignoring the sofa, I sat on the floor, while Yu brought out mugs and packets of South Korean instant coffee. Guk opened the refrigerator and took out cans of Asahi beer and a basketful of Japanese sweets.

Guk asked the third man, who sat quietly on the floor, how his travel plans to Germany were coming along, and the man said that he would be leaving in a few months. From the look of him—small, gaunt, shabbily dressed, with eyes lowered—it was hard to imagine that the trip was for leisure. Yu asked him about his family “over there.” As was the case with Guk, the man was ethnic Chinese from North Korea and still had family in the country. Because of his nationality, he was allowed to travel between China and North Korea. A trustworthy messenger was worth gold in this business, Yu later told me.

Yu and Guk chatted for a while in what seemed to be a code. There were several mentions of a “grandma” and how difficult she was being. This grandma was hanging around longer than expected, and both Yu and Guk were getting increasingly anxious about it. When I asked whose grandma she was, Guk laughed and said, “Oh, it’s our way of calling women in general, any woman past her twenties. This particular grandma is in her early forties, maybe in her late thirties, not sure, women are all the same after a certain age, and she sure is a pain in the ass.” For a moment, I was afraid that he was talking about me, but soon it became apparent that this “grandma” was a Korean woman who had flown in from Japan a couple of days ago, bringing with her something for sale, and rather than leaving it up to Yu to finalize the deal, she was waiting around to personally meet with the messenger from North Korea who was currently on his way over to Dandong.

Yu lamented the unpredictability of his contacts. He and Guk began discussing how hard it was dealing with “them” because they phoned infrequently and guaranteed no time of arrival. Even for these men, interactions with North Koreans was a test of patience.

What he was saying seemed eerily reminiscent of the current political climate. There had been no warning when the North Korean government barred South Koreans from the Kaesong Industrial Complex; the factory owners had been quoted as saying that they had grown frustrated with such unprofessional behavior. I had also observed something similar in my relations with my North Korean students when I lived undercover in Pyongyang. The moment they seemed to open up, they inevitably retreated. It was no surprise, really. How could real relationships develop in a place where trust can lead to death and fear governs everything?

At night, the contrast was even starker. Both the city of Dandong and the Friendship Bridge were lit up like Christmas, as though the Chinese side were taunting its troubled neighbor across the river, where darkness fell, in near pitch black, as though no one lived there. Then I would wake up to face the bleak view, and a part of me wondered what I was hoping to find in this godforsaken place. Yet another part of me, an insistent voice inside, kept hanging on, hoping to gain another perspective of North Korea, which had become a siren call haunting the past decade of my obsession with it. Why Haruto-san left me alone with Yu was a mystery. Why Yu agreed to spend time with me was also odd, but he obliged, grumbling that he got stuck babysitting Haruto-san’s friend.

One afternoon, Yu and I were eating Pyongyang naengmyun, a buckwheat noodle dish popular in both Koreas, and his phone kept ringing. He would answer only to discover that he had lost the signal. He explained that phone connections were always a problem here because North Korea broadcast noise on the same frequency as radio shortwaves to prevent unwanted foreign programs from reaching its people. When his phone rang again, he looked at it without picking up, and said that whoever was calling was frantically trying to get his hands on what he had in his backpack. He unzipped it to show me the inside filled with bundles of fresh $100 bills. “Thousands?” I asked, and he chuckled as if pitying my naïveté. “More like one hundred times that.”

This was the only time Yu came to see me without Guk, and he told me his story. He was born 50 years ago in South Korea, he said, and became interested in North Korea in his youth. He had lived abroad in China and Thailand for the past two decades and supplied the South Korean government with information about North Korea for seven years. But some time during the mid-2000s, the South Korean national intelligence service brought him in for questioning, and tried to frame him as a spy. They needed a scandal to heighten the inter-Korean tension and chose to sacrifice him. He avoided arrest by threatening to expose them to his contacts in the Japanese media. Since then, he never stayed in South Korea for longer than a few days at a time.

People came to him looking for information about North Korea. Ninety percent of those were from corrupt defector aid groups that pretended to help rescue defectors but instead only pocketed aid money raised in the United States and South Korea. Then there were various governments, each offering him an average of $10,000 a month on retainer. When I asked if that was how much Haruto-san was paying him, he shook his head and mumbled, “I’m just a common merchant.”

Yu claimed he preferred China to his native South Korea. There were no rules here, he said; it was a lawless world that gave breaks to men like him. Yet it had taken him years to find his footing in Dandong. People often had multiple alliances. They might have a link with the South Korean government, maybe Japan, maybe Russia, or maybe with the Chinese police. You never know, so you should always watch everything. Never assume anything.

With his apartment, he finally had an ideal setup; most deals took a lot of waiting. He once stayed in a motel in Donggang, a small port city about 20 miles southwest of Dandong, for nearly a year to recruit a contact. A large number of North Korean contract workers were sent to the Chinese factories there, and North Korean ships docked there regularly. When a ship came in, the crew came off the boat and went to a Korean store to stock up on food. Yu had courted the Korean-Chinese proprietor so that she would alert him when the crew arrived. Then he would rush over with a bag filled with cartons of Japanese cigarettes conspicuously sticking out. Not just any cigarette, but Seven Stars, which came in slim yellow packs sold only in Japan and at duty-free shops at Narita Airport. “But pay attention, this is important!” Yu said impatiently, as though he were giving me a lesson on how to recruit North Korean sailors. “Never approach them first—let them approach you!” Sure enough, after a few of these “chance” encounters, the captain of the ship ventured over to him, and asked where one might get hold of those Seven Stars. In order to gain his trust, Yu introduced himself as a Japanese businessman of Korean origin from Tokyo. The next time he came through, he could get the captain a few packs. They became friendly that way, and after months of bringing him cartons of Seven Stars, Yu knew that he could get the captain to do him some favors as well.

“What favors?” I asked.

Yu was vague as usual, but from the bits he said here and there, I gathered that the captain would contact a specific person in Pyongyang with a certain message. How could he be sure that this captain went to Pyongyang? “That’s easy,” he smiled. Yu made him carry a GPS so he could track him. This confirmed something Haruto-san once told me about their relationship: Yu helped him make contact with high-ranking officials in North Korea.

Then Yu, rather boastfully, began telling me he had been the first one to alert Haruto-san about Kim Jong-il’s death in December 2011. No one had any idea; in fact, even within North Korea, only a few people had been notified. But Yu figured out what was going on when a meeting with his North Korean contact, a high-ranking official, was abruptly canceled, and the official made a swift return home. Yu then telephoned Haruto-san, who immediately flew over from Japan to confirm, and thus it had been from his information network the Japanese government learned of Kim’s death before anyone else. It was a cold winter, Yu said, as the two of them waited in Shenyang through Christmas for further news from within North Korea.

I was not sure how much of what he was telling me was true. But I was not being perfectly frank either. I did not share with him that I had been in Pyongyang on the day of Kim’s death. People often asked me afterward what it was like in that moment, and I never knew how to explain or where to begin. I did indeed witness the darkness dawning on the face of every North Korean, as though they had just lost a parent or god, but my cover there had been as a teacher, and I was not allowed to leave my compound. I could only attest to what I was allowed to see, which is inevitably how one assesses one’s experience of North Korea.

We met like this a few more times, with Guk accompanying Yu, over MSG-covered food. Soon I began to feel that even the water there tasted of MSG, and sometimes I wondered if MSG were the new opium for a billion Chinese. Yu always carried a backpack filled with cash bundles. Once he went off to the bathroom, leaving the backpack on the seat just as Guk stepped out for a cigarette, and I wondered if they were testing me. I still could not understand why Yu spent so much time with me, and each afternoon toward dinnertime, I worried that he might just not show up. One day, when I was told that the contents of the backpack added up to $70,000 and 900,000 Japanese Yen (roughly $8,000), I asked again what the money was for, and Yu shrugged and answered, in his cryptic way, that it wasn’t for drugs but instead “something very sweet.” Although he would not let me meet the grandma, a meeting between her and the messenger from North Korea finally seemed to have taken place, since she had left Dandong. To celebrate, Yu and Guk suggested a picnic.

During the hourlong drive along the Yalu River, the radio picked up a North Korean broadcast. The program was an interview with nine defectors who had recently been captured in Laos and sent back to North Korea. The interviewer asked one of the defectors to explain how he had gotten out of the country. He answered that he had originally been kidnapped from North Korea by a South Korean Christian minister and his wife and had been held against his will in Dandong. If he failed to memorize and recite passages from the Bible he was beaten. One night, after two years of captivity, he was shoved into a car to be sold to South Korea, and it was with the solicitude of the Great Leader that he was rescued and returned home. The others repeated this story, and the interviewer said how miraculous it was that they had escaped the hell of such kidnappers. The entire time, they ranted against “that asshole bastard minister.”

Yu laughed as he listened, and Guk pointed out that the program was for an international audience since defection was not a topic openly discussed within North Korea. The idea was to show the world that repatriated defectors were not executed or sent to a gulag, as was widely reported. Guk turned the radio off, and then stopped the car at a gas station and ran out to buy something. “For lunch,” he said when he returned, holding up a small container of gasoline.

All around us were rolling hills, and our car veered off onto an unpaved side road, which ran downhill. We soon reached a small bridge over a dried-up riverbed full of rocks. It was a sunny afternoon, and there was a van parked there. In the shade beneath the bridge a group of men sat drinking cans of Tsingtao beer. A huge man, his head shaven and his bare chest covered in tattoos, looked up and shouted out something in Chinese. Guk waved as he opened the trunk and took out a crate. The bald man walked over, and together they carried the crate from the car and set it down in the shade. I watched them, wondering what might be inside the crate, but part of me felt afraid and did not want to know. Whatever it was, it appeared to be heavy. They gathered small stones and spread them out on the ground, then covered them with a hemp rice sack. Guk opened the crate and took out something that looked like a stone but turned out to be a clam the size of a child’s fist. The crate was full of humongous clams. He stacked them vertically so that each one was propped up by stones beneath the cloth. They did this until there was a neat pile of clams over which Guk splattered gasoline; then he lit them all on fire.

“North Korean clams roasted in a North Korean way!” Yu shouted. He was seated on a rock next to the men, who were drinking silently and eating some sort of grilled meat. I asked Yu where these clams came from and who these men were, but he only said that they were Guk’s friends and did not understand Korean so I should not pay them much attention. The blaze lasted only a brief while and died on its own, and Guk and the bald man brought over a pile of hot clams on a piece of cardboard.

“Those guys are Chinese so they won’t eat them cooked this way,” Yu said, referring to our companions. Indeed, the men glanced over at the clams with curiosity but did not touch them. Guk explained that although he too is Chinese, he grew up in North Korea and used to cook clams like this with friends. Yu opened one and offered it to me, saying, “If you are researching North Korea, you better try it, since this is what they eat over there—well, those who get to keep the clams they catch.”

I did not see how I could refuse. Of course, it was not clear why we were nibbling on gasoline-bleeding clams under a bridge that seemed hardly a scenic spot for a picnic, surrounded by tough-looking men who could not be conversed with. The clams tasted leathery, without much flavor. I worried about some sort of cancer forming in my body with each bite. Both Yu and Guk kept exclaiming how delicious they were.

The next morning, Yu was in the worst mood. The grandma had been stopped at Shenyang Airport and $90,000 was confiscated from her. Yu was furious since $20,000 of the cash was his, and it would take about two months of fighting with Chinese officials to get it back, minus a steep fine. The grandma had wrapped the cash in aluminum foil, which would increase the fine since it showed intent to conceal. Yu had told her never to do that, but she did not listen. I was not sure why she was carrying his share of the profit, but what was clear was that the woman was taking cash with her back to Japan, which seemed to suggest the money was a payment from North Korea for something she had sold. Yu and Guk both had to leave for Shenyang immediately to resolve the matter, but before taking off, Yu asked to speak to me in private.

“You are an amateur. Not even good enough to be an amateur!” he said, meeting my eyes across the table in the lobby of my hotel.

At first I thought that he was so angry about the lost money that he had decided to take it out on me, but then I realized there must be another purpose to this sudden attitude shift. “You ask too many questions. In our world, the number one rule is not to act interested even if you are. You really should leave this game; it will only make you smaller and more pathetic the longer you stay, because you understand nothing about the players. Everyone’s laughing at you. Even my guys are laughing at you.”

He explained that the Chinese men under the bridge were the biggest gang members in the region, and the bald man with tattoos was so notorious that the moment he entered any restaurant, the place emptied instantly. Yu needed such men for protection. He had no time for someone like me, he said, but Haruto-san had asked him to look after his dearest friend. I knew by now that things here were said in codes, and that Yu was trying to tell me something. I was barely an acquaintance of Haruto-san, certainly not a dear friend, and Yu was a smuggler and would not be wasting time on me without a motive. It was as if he was trying to rile me up so I would finally show my hand.

“You are so mistaken if you think North Korea gives a shit about the American threat of sanctions,” he continued. “What makes you Americans think that North Koreans are poor? Look, the person who came out the other day from Pyongyang is Boss Kim. She is part of the official delegation, carrying a diplomat visa, and drives a Benz and owns a high-rise pied-à-terre here in Dandong. Each time she comes out, she brings a load of cash to buy stuff for the Party leaders. Sometimes diamonds—but only above one karat, costing at least a few tens of thousand dollars. Sometimes Ballantine whiskey, 30 years old—but never from a duty-free shop; directly from Scotland. It costs double but they don’t want anything made in some second-rate country’s factories—only Japanese stuff made in Japan, only French stuff made in France. Their leaders only want the top quality. The rich are richer over there since there’s no labor cost, and things get done by just terrorizing people.”

The transaction between the grandma and Boss Kim, one from Japan and the other from North Korea, appeared to have taken place two days ago in Yu’s secret apartment, after which the grandma left for Shenyang. But I had met neither of these women. I needed proof that they existed; otherwise, it was just a story. But I also knew that proof in this business came with a price tag. Yu was now tapping the table in exasperation. I could see that he had finally reached the point he had been leading up to.

“What I’m amazed by, though, is the fact that you have no idea. Your country has no idea. Everyone knows this except America. China knows, South Korea knows, Japan knows, but only America has no idea how North Korea works. Your country is being left seriously behind.”

If this were a sales pitch, it was quite specific, and I recalled him quoting the $10,000 per month retainer. This, apparently, was the price for the United States to get back in the loop, which did not seem like such a bad deal. Except that I was not a spy, here to recruit him, as I now realized he believed. I was pondering this when he got up and said:

“There’s a comedian I really admire in your country, and I would love his autograph because he’s such a fine actor and is making all of us who know what’s going on laugh constantly. He is so funny, making such bogus grand claims about the ‘Korean problem’ while doing absolutely nothing. Could you get me his autograph?” He looked at me coyly and added, “His name is Barack Obama.”

After Yu left, I stopped by Dandong’s Korean Community Center to meet with the South Korean minister who had once warned me about coming here. When he heard about my time with Yu, he declared that I had narrowly escaped real danger. $90,000 is a lot of money, certainly too much for cosmetics. If the local Japanese-Korean merchant came herself to collect money and deliver, whatever it was must be small as well as significant, most likely weaponry components. Japan is known for supplying such things to North Korea, including GPS-jamming devices, which could fit into a backpack. If one of Yu’s men was off to Germany, it seemed likely that he was going there to acquire high-tech equipment. What reason could any of these men have for traveling to Germany for work if not to acquire something? In the world of Dandong smugglers, there are clear reasons for each destination: The U.K. suggests Rolls Royce and Rothman cigarettes. France means fine wine. Germany means high-tech parts.

As for the true identity of Yu and Guk, he had never heard of a South Korean in Dandong named Yu fitting such a description; but Guk he knew well, and he was no Chinese born in North Korea, but a Korean born in China. These men lie to convey legitimacy, he said; if you want to be in the business of selling North Korea, you have to pretend to know it better than others.

That night, my Air China flight out of Dandong was canceled, and I got stuck in a dismal motel near the airport, which resembled a rural Greyhound station. Since I spoke no Chinese, I relied on two fellow Korean-speaking passengers for updates on the flight. One of the men claimed to be Japanese, the other Chinese, both supposedly strangers to each other. The three of us ended up drinking beer while waiting.

I asked what brought them to Dandong, and why it happened that they were fluent in Korean. One pulled out his phone to show me a photograph of a painting of a mountain, very detailed and colorful. He said that he was an art dealer specializing in paintings from North Korea. The other man also used his phone to show me a photograph of what looked like ginseng root. This was, however, the much rarer sansam root, which normally grows to about five centimeters at most, but in North Korea is reputed to reach as tall as two meters and is believed to have healing properties for all manner of ailments. They sell for $10,000 a root, mostly to South Korean buyers. The next photograph was of a huge bullfrog. North Korea lacks industry, and therefore pollution, so things grow with no bounds, he said. These frogs sell for $15 each to Chinese clients, and he had a contact in North Korea who could get him an unlimited supply. “How about that, Miss America,” he said, shoving the photo of the frog in my face. “You think maybe anyone in America might be interested in buying these natural North Korean Viagra?”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!