Who is JW00237? The secret Canadian campaign to ban Huawei’s Chinese ‘spies’, and the anonymous official at its heart

- Canadian immigration officer ‘JW00237’ branded three Huawei staff spies in 2016, an effort cast in new light by the US pursuit of the firm and CFO Meng Wanzhou

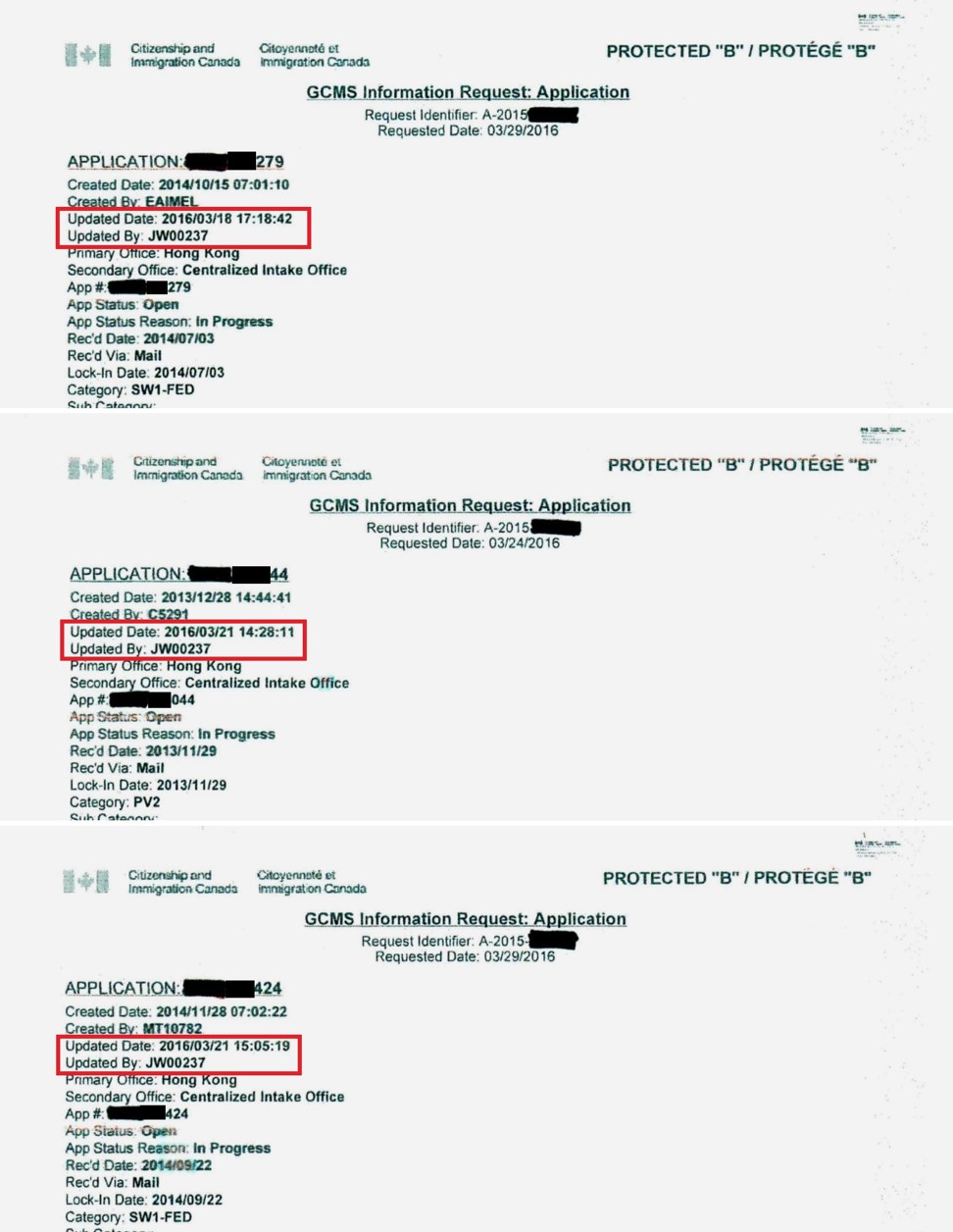

- Time-stamped documents obtained by the SCMP show the officer tried to veto all three unrelated applications in four days, processing two just 37 minutes apart

Updated: Wednesday, 6 Mar, 2019

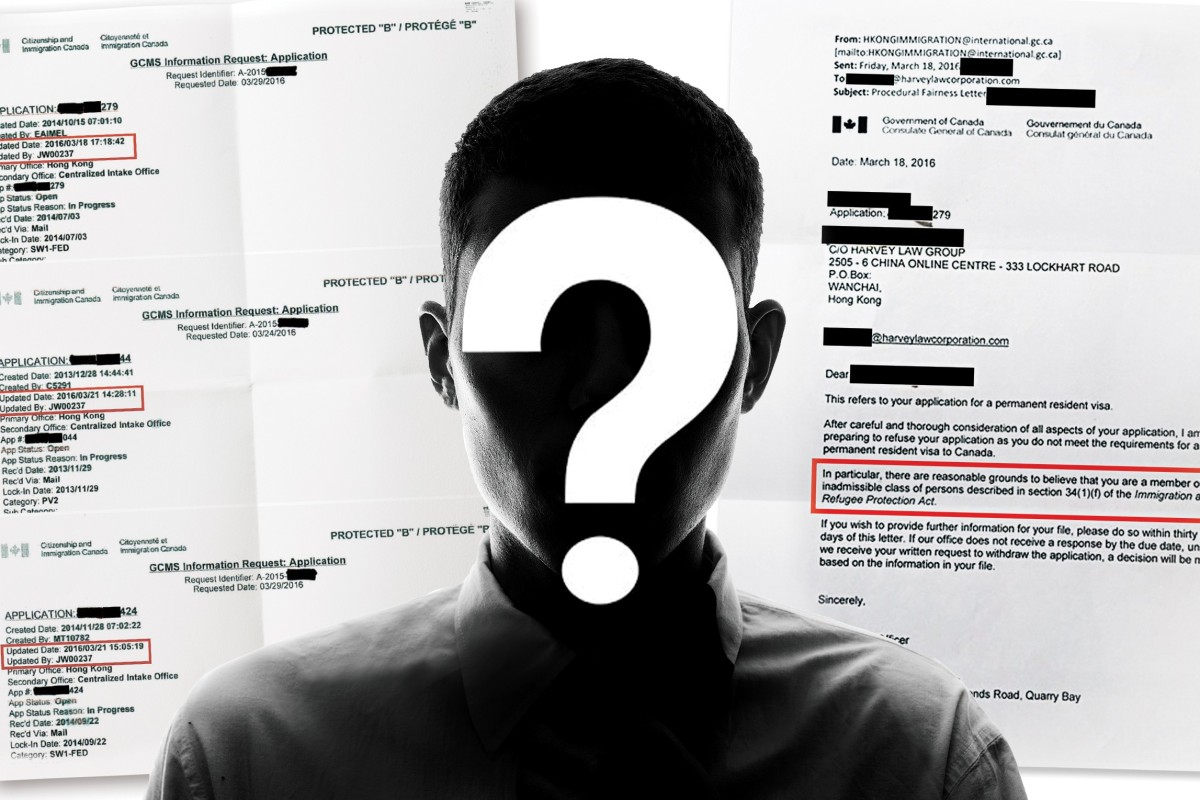

*The same Canadian immigration officer, identified only as ‘JW00237’, tried to ban three Huawei-linked immigration applicants in the span of just four days in 2016, documents obtained by the South China Morning Post show. Photo illustration: SCMP

Beginning in autumn 2013, over the span of 10 months, three Chinese citizens applied separately to immigrate to Canada.

They applied variously under a skilled-worker scheme and a provincial programme favoured by wealthy businesspeople. Two planned to move to Toronto, one to Saint John in New Brunswick.

Their paperwork joined the tens of thousands of Canadian immigration applications being processed at any given time.

Besides nationality, the only thing the three applicants all appear to have had in common was that they or their spouses worked for Chinese telecoms giant Huawei Technologies.

Yet somehow their applications all ended up on the desk of the same Canadian immigration officer in Hong Kong, repeatedly identified in documents obtained by the South China Morning Post by the initials JW and the numerical code 00237.

And in the space of just four days in 2016, the documents show, JW00237 told the trio their applications would be rejected, on the grounds that they or their spouses were believed to be spies.

‘You are a member of the inadmissible class of persons’

Hong Kong-based Canadian immigration lawyer Jean-Francois Harvey, who eventually represented all three applicants, once believed the stunning accusations were the work of JW00237 acting alone as a “rogue” agent.

But a different light is now being cast on JW00237’s efforts, as details emerge of a complex, years-long effort by the US to target Huawei – culminating in Canada’s arrest of chief financial officer Sabrina Meng Wanzhou on December 1 at US request.

Documents obtained by the South China Morning Post show the same Canadian immigration officer ‘JW00237’ processed three applications by Huawei employees and a spouse within four days in 2016. Two of the otherwise unrelated applications were updated 37 minutes apart. Graphic: SCMP

Harvey now suspects a secret and systematic effort to target Huawei employees as spies may have ensnared his clients.

Newly obtained documents show that JW00237 was handling two of the otherwise unrelated Huawei applications simultaneously, updating their files within about half an hour of each other.

All three cases had been initiated by different officers, the documents show.

The three cases only came to light because the applicants happened to use the same Chinese immigration consultant, who noticed the refusal pattern and forwarded their cases to Harvey, and all applicants decided to challenge their rejections.

How many, if any, other Huawei staff have been similarly targeted, and whether that process continues, is unknown.

Immigration lawyer Jean-Francois Harvey represented three Huawei-linked immigration applicants, who were all accused by Canada of being spies – accusations that were eventually retracted. Photo: SCMP

In a statement, Huawei said it had no record of employees being denied Canadian immigration approval. A “significant number” of successful applications over the years by Huawei staff “strongly reaffirms our belief that this matter has nothing to do with Huawei”.

But the Post has confirmed the identities of the trio targeted by JW00237, and that one still works for Huawei.

For the three applications to have randomly ended up for consideration by the same immigration officer within a few days would have been wildly unlikely, Harvey said.

“At that time, they have thousands and thousands of [immigration] cases in the inventory,” said Harvey. “How coincidental can it be?”

And a former Canadian immigration officer, who requested anonymity, said that staff did not normally have individual discretion to choose which cases they handled, making it “very unlikely” the cases randomly ended up with the same officer, or that the officer was acting without permission.

“It’s not possible, not likely, that one guy randomly has three Huawei cases fall on his desk … there has to be some kind of discussion [with] a supervisor,” said the former Hong Kong office supervisor.

The Post

on Harvey’s clients in 2016.

Canada backed down in the face of an appeal by Harvey. His clients – who strongly denied being spies – were allowed to immigrate to Canada.

But the original designation of the Huawei trio as spies was an extraordinary step; in his career as one of Hong Kong’s top immigration lawyers, Harvey had handled more than 12,000 Canadian immigration applications, but had never before seen a client barred on the grounds of suspected espionage.

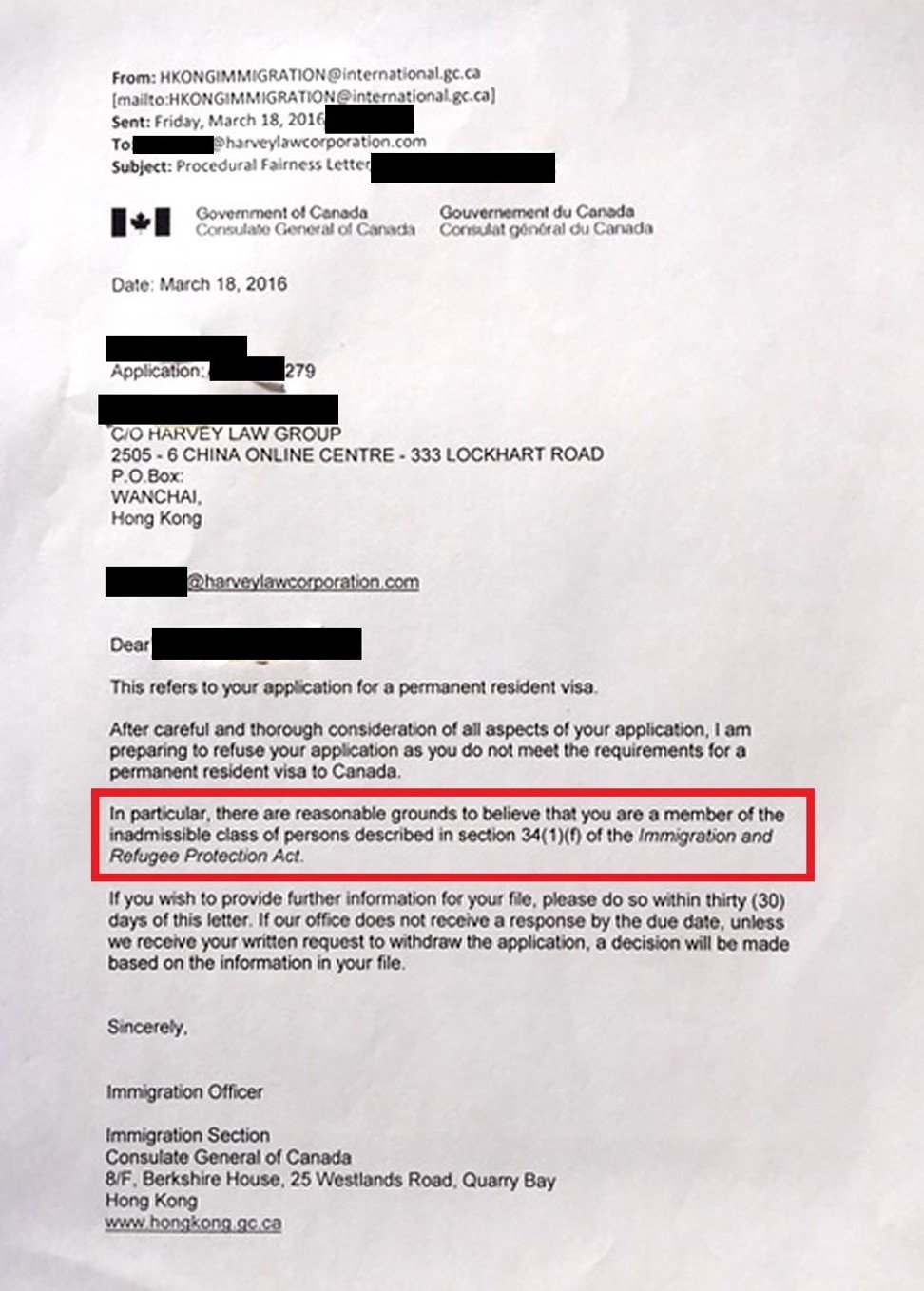

A ‘procedural fairness’ letter to a Huawei employee shows that Canadian immigration officer JW00237 tried to reject them on the basis that they were suspected of espionage on March 18, 2016. Graphic: SCMP

The Post knows the identities of the Huawei-linked applicants but has agreed to maintain their anonymity under the terms of discussions with Harvey and others familiar with their situation.

The Post – which does not suggest that Harvey’s clients had any link to espionage – has also agreed to no longer attempt to directly contact the applicants, who are said to fear the reaction by Huawei to their broaching such a sensitive subject with the media.

Client A applied to move to Canada on July 3, 2014, as a skilled worker. The application proceeded normally until March 18, 2016, when the client received an emailed letter from JW00237, based in the immigration section of Canada’s Consulate-General in Quarry Bay, Hong Kong, saying the officer was preparing to reject their application.

“[There] are reasonable grounds to believe that you are a member of the inadmissible class of persons described in section 34(1)(f) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act,” the so-called “procedural fairness” letter said.

refers to people who belong to an organisation engaged in espionage, government subversion or terrorism.

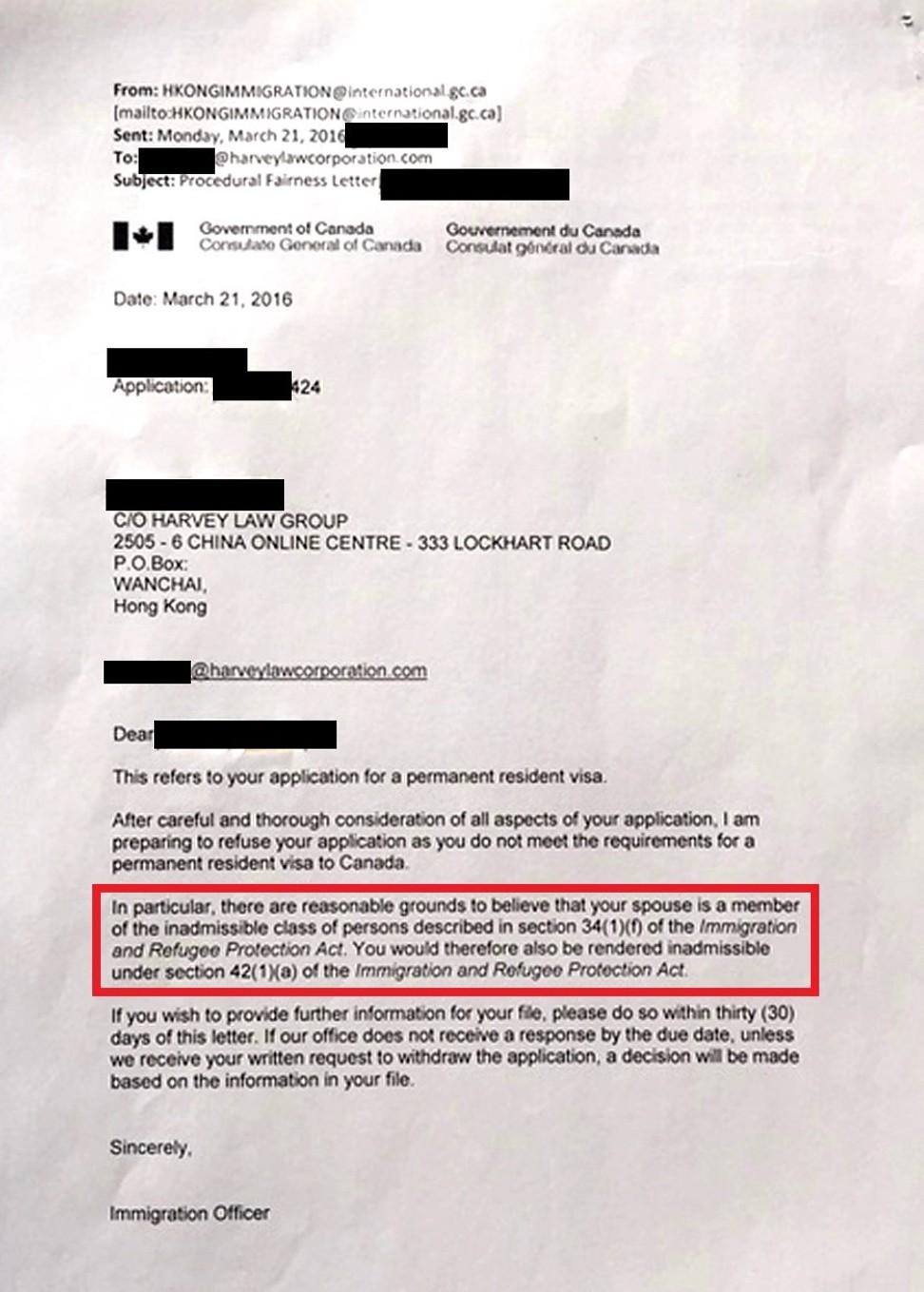

Then on March 21, Client B and Client C both received similar letters, the latter’s flagging the spouse who worked for Huawei as the suspected spy.

A ‘procedural fairness’ letter, dated March 21, 2016, to a person married to a Huawei employee shows that Canadian immigration officer JW00237 tried to reject the applicant on the basis that the spouse was suspected of espionage. Graphic: SCMP

Client B had applied to immigrate on November 29, 2013, while Client C’s application had gone in 10 months later, on September 22, 2014.

Yet time stamps on immigration documents obtained recently by the Post show that Clients B and C’s applications were updated on the same afternoon in 2016 by JW00237 just 37 minutes and eight seconds apart.

The Post asked Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) for a general description of how applications are processed and whether individual officers had discretion to choose cases.

Cases were typically handled in the order they were received, a spokesperson said.

“In general, managers assign files to decision-making officers to process and they are processed on a first-in, first-out basis,” they said.

Between the first and the last of the Huawei-linked applications being submitted, 87,379 other Canadian immigration cases were set in motion, according to their sequential case numbers.

Berkshire House in Quarry Bay, Hong Kong, where the immigration and consular sections of Canada's Consulate-General are housed. Photo: Swire Properties

When asked specifically about the Huawei cases and how they all ended up with JW00237, a different IRCC spokesperson said in a statement “that in order to maximise efficiency specific files are sometimes assigned to the same immigration officer for assessment”.

The statement said this was not a comment about any specific cases.

The spokesperson said that “for privacy reasons and to ensure the safety of its employees” IRCC could not identify JW00237.

The agency did not respond when asked whether other Huawei staff had been flagged as spies, or whether IRCC had specific practices in place for the handling of Huawei employees.

‘The only logical conclusion is that the employer was targeted’

There she remains on C$10 million (US$7.5 million) bail while awaiting an extradition hearing; she is due back in court on Wednesday.

As far back as July 2007, a New York grand jury said in a January 24 indictment, the FBI interviewed Huawei’s billionaire founder Ren Zhengfei, Meng’s father, quizzing him in New York about the company’s dealings with Iran.

The indictment does not name Ren, but instead refers to “Individual-1” as the founder of Huawei.

Now here's a happy chap, complete with a broad smile...

Ren Zhengfei, founder and CEO of Huawei, was questioned by US investigators in New York in July 2007. The probe was only revealed this January, in a US indictment of the firm. Photo: AP

“During the interview, among other things, Individual-1 falsely stated … that HUAWEI did not conduct any activity in violation of US export laws,” the indictment says.

Then, in early 2014, Meng was stopped at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York; before she was allowed on her way, US agents fossicked through one of her electronic devices and allegedly found evidence of a file relating to the way the company did business in Iran.

Huawei was already under public scrutiny: in October 2012, a US House intelligence committee concluded the firm posed a national security threat and should be blocked from US acquisitions, takeovers, or mergers.

That triggered a wave of discussion in allied countries about the wisdom of doing business with Huawei.

But the indictments revealed that a parallel effort against Huawei had also been initiated by US law enforcement and intelligence officials, a pursuit that casts the treatment of Harvey’s three former clients in a new light.

The Canadian action against the three would-be immigrants – who applied around the same time Meng appeared on the FBI radar – represented another secret level of attention: direct accusations of espionage against specific individuals.

Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer of Huawei Technologies, leaves her homes while out on bail in Vancouver, Canada, on January 10. Photo: Bloomberg

Canada and the US are part of the so-called “five eyes” intelligence-sharing network of Western nations, along with Britain, Australia and New Zealand.

Meanwhile, a Chinese sales director of Huawei and a Polish former intelligence agent were

last month on suspicion of spying.

Lawyer Harvey said the treatment of his clients was “very, very intriguing”.

“That these three cases, at three different stages of processing, different programmes, end up on the same person’s desk at the same time, the same officer, out of thousands of cases,” he said.

“What are the chances? Does the processing system of Canada immigration allow one officer alone to say, oh, I’ve got one Huawei [employee], I want others. I don’t think so. I don’t think the system is like this.”

The former Canadian immigration supervisor agreed.

“Files are distributed kind of randomly” although a supervisor could allow an officer to assess specific applications in which a pattern had been detected. “It couldn’t be the case [though] where an officer picked them all out by themselves … it would be approved by someone above them.”

FBI Director Christopher Wray speaks alongside (from left) US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, then acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker, and Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielson as they announce indictments against Huawei and Meng Wanzhou on January 28. Photo: AFP

He said any visa refusal – let alone a series of unusual ones – would expose a “rogue” officer to scrutiny.

“Any time a visa officer makes a controversial decision, a refusal decision, he has to realise this is probably something that will come up. There’s a good chance the client will lawyer up and contest the decision and everyone sees what you have done,” the ex-officer said.

“For this officer to ‘go rogue’, and get all the Huawei cases [without approval]? It’s very risky … his supervisor would ask, ‘hey, how did you get all these Huawei cases?’”

Harvey spoke of his growing suspicion that the targeting of the trio was systematic the day after the indictments against Huawei and Meng were released last month.

“The only logical conclusion is that the employer was indeed targeted,” said Harvey in a subsequent email, noting the huge number of other cases separating the applicants, and adding that this was “now clear”.

Harvey said in the earlier interview that if other Huawei-linked applicants decided not to challenge the same sort of accusations levelled at his clients, then these would likely remain secret.

To rebut the accusations, Harvey said he simply provided signed statements from his clients that they were not spies. He declined to provide the statements, citing lawyer-client privilege.

A different Post source directly familiar with Harvey’s clients said that although all denied any involvement in espionage, Client B believed “there could very well be some truth to the allegations [about spying by Huawei]”.

The source depicted an employee fearful of identification, because going public with the sensitive situation would offend Huawei; after becoming aware of the other two applicants’ cases, Client B contacted them and urgently persuaded them not to directly communicate with the Post.

An interview with Client C and the spouse was called off a few hours before it was scheduled, apparently as a result of Client B’s lobbying.

“He’s very, very concerned, very, very reluctant to have this story come out,” said the source. “Why? Because he said that Huawei has the means and the capability to find out information and he really fears [that his] identity gets out.”

Client B described himself to the source as being personally familiar with Huawei founder Ren, although the Post has not been able to confirm this.

“It just seems so ironic that these three employees are being accused of being part of an organisation that has been accused of doing [espionage].

“These employees themselves have not been involved in it, yet based on what this executive told me, there could very well be some truth to the allegations [about Huawei],” the source said.

“Where there’s smoke there’s fire. So it’s a little bit ironic. No, they’re not, individually they’re not involved in any of this stuff. But based on what he was telling me, maybe, yes [Huawei is].”

In its statement, Huawei said it had “well-established Canadian business and research operations in Canada since 2008”.

“We have employees travelling between Canada and China regularly with travel visa and work permit approvals issued by the Government of Canada. In addition, over the years, a number of past or retired Huawei employees have successfully immigrated to Canada, with employment at Huawei used as a reference,” the firm said.

“Given the positive nature of our working relationship with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, the well-established process for managing applications, and the significant number of successful applications over the years, all of this strongly reaffirms our belief that this matter has nothing to do with Huawei.”

In accordance with their wishes, conveyed via a third party, the Post has not attempted to directly contact any of the applicants since 2017.

The Post recently requested interviews again, via a different third party, who said that two refused to comment, other than to confirm that they no longer work for Huawei, while one received the request but did not respond.

Retracted accusations and a mystery unresolved

At least one other aspect of the three immigration cases appears unusual – the manner in which they were eventually resolved.

Harvey said the identity and reasoning of JW00237 would have had to be revealed in legal proceedings if the Canadian government had fought his clients’ claims of unfair treatment.

But instead, after Harvey submitted his clients’ sworn statements that they were not spies – and the Post reported their situation – the government retracted the accusations without comment and approved the applications.

As a result, their cases never went before the public forums of a court or an immigration tribunal hearing.

Lawyer Jean-Francois Harvey: “The only logical conclusion is that the employer was indeed targeted.” Photo: SCMP

“If I had to go to federal court then I would have had full access to their files, to see what was wrong,” Harvey said.

“But that was the surprising thing in those three cases: there was no correspondence from IRCC [after the sworn statements were made]. Then suddenly, bang … you can put the visa in the passport.”

He added: “As a lawyer, my only concern is my clients’ interests. I’ve got the visas, so I have to stop there.”

From Harvey’s perspective, the identity of JW00237 and the motivation had become moot. They remain a mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!