A POLICEMAN’S STORY

Even today, more than 20 years after the Walled City was demolished, the myth that the police never entered the Walled City persists. Many people, it seems, are drawn to the idea of a community that exists totally beyond the reach of the law. Imagination takes over and a romanticised vision quickly evolves that is difficult to dispel. A story that evokes a shiver of excitement or disbelief, however outlandish, will always outdo mundane reality.

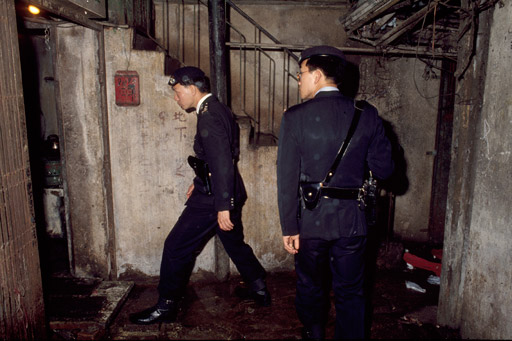

This is certainly true of the Walled City, even though the reality could hardly be more different. The police were, in fact, patrolling in the City from the beginning, and while it is true that there was a considerable amount of illegal activity there during the 1950s, after that time the City was little different to many other parts of working class Hong Kong. Here below are the recollections of a police officer with several years experience of patrolling the City. He spoke to us in 1990, without authorisation, and asked that we not identify him, so the accompanying photographs are of other police patrols met by chance in the City.

“I joined the Police seven years ago. I was first stationed in Tai Kok Tsui, then I became a Blue Beret and was transferred to Kowloon City. The Walled City used to come under the Mobile Police Unit assigned to the area, but now it’s under the Task Force. It was a sensitive area, of course, but it’s been a long time since the City was out of bounds.

I was posted to City in 1985, and have patrolled there now for five years. I adapted to the place quickly. I was older and quite used to having contact with the sort of people you come across inside. In fact, police work in the City was similar to our work elsewhere. There used to be a rule that two or more policemen would have to go on patrol together, and there had to be memo from the Regional Command Centre stating the names of those going in, but now that’s changed and any policeman can go it alone.

When the Sai Tau Tsuen settlement next to the City was being demolished, in 1985, there were just six of us responsible for the Walled City area – two people on each of the three beats a day. Now, with the clearance under way, there are more. When we went on patrol, we had to sign 11 report books, while on a normal beat outside the City you’d sign just two or three.

When I first took up my assignment, the City was still thriving and everything was very much out in the open. It’s become so quiet these days! There were prostitutes soliciting on the streets; they usually had their regular spots. There were child prostitutes as well. Now only the older ones are left. Yes, there were quite a few goings-on then that are probably best left untold. For example, a colleague arrested some men for possession of bombs brought in from China; no one seems to have heard anything about this!

The City has never been that much different from other areas, though. In some ways it’s actually quieter and less sophisticated. One special feature about the place is that roof-tops on the buildings are connected to one another, so you can just ‘fly’ here and there! The unusual conditions mean that there are few car thefts of course, but there are more burglaries and robberies. We are aware of the black spots for crime and patrol them more often. The incidence of theft is high; the most troublesome time to be on shift is between 3pm and 11. There are regularly three or four reports of theft during that shift.

At one time there was also a lot of drugs – all completely open again, both in terms of selling and manufacturing. Packets were sold in the streets. I believe there’s still some of that going on. As policemen, we can’t just barge into people’s premises, but we pass on information that we hear and leave it to the Narcotics Bureau to sort out. They operate there as well.

There used to be close contact between the police and people inside the City, including those who had special connections. The younger policemen nowadays don’t have much of a clue about this. The people who hold the power in the Walled City are the Chiu Chows. There was this one guy in particular, Chan Sup, the ‘big brother’ of the Sun Yee On Triad. He died recently and there have since been lots of fights between those carving up his interests. I quite respected Chan; we knew each other and he was kind of loyal to his friends and those he knew well.

Things used to operate differently in those days. When a problem needed sorting out, we asked for the ‘big brother’ and he would promise to do something to fix the matter. Working with some of the criminal elements in the City, we could usually settle quite a few problems. Occasionally we didn’t even need to go into the City to get things done. Take, for example, some of our drug-busting. Whenever it became necessary, we’d inform people inside that things needed to be done and the police would get their guy. At other times, we’d feel quite helpless. Methods that worked outside the City might not always apply inside.

You could say that some Triad groups had their origins inside the Walled City – groups like the Sun Yee On and 14K. It’s true also that some policemen were on the take, but since the setting up of the ICAC [Independent Commission Against Corruption] that’s pretty much stopped. The City had fabulous pieces of what we call ‘fat pork’ and, in the past, the police did things very differently. They had their own groups and factions that were responsible for the area. There might still be a little of it going on. I can’t tell for sure.

We used to find quite a few illegal immigrants working in the factories. Like the criminals, they tried to claim the Walled City was Chinese territory and that they were immune from arrest. At times, the factory owners themselves informed us of such immigrants so as to avoid paying them. That’s human nature, I suppose!

It took 36 hours for Government officials to register all the residents and housing units following the announcement of the clearance. Actually, on the evening after the announcement, dozens of lorries brought furniture and other things back to the City and some people tried to offer us a pay-off to testify that they had been a resident for a certain length of time! But by then the City had been sealed off.

How did I like working in the Walled City? I have to admit I enjoyed my time there – I got to see and understand things you don’t find elsewhere in Hong Kong, like opium dens with people lying on the floor smoking. I saw them but couldn’t do anything. I also got on well with the residents – I even played mahjong with them sometimes.”

IN PRAISE OF OPIUM

Cathie Breslin, author of the article The World’s Wickedest City (see below), was not the only journalist to enter the Walled City in its early years to taste – and write about – the delights or otherwise of opium. Breslin had visited the City in 1963 and was not taken with her experience of smoking opium, but five years earlier she had been preceded by a British journalist, Lois Mitchison, who had found the drug much more to her liking.

She recounted her experiences in an article for The Spectator, published in May 1958.

“The first time I smoked opium was with Hank, the American news-film photographer, in Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong. Hank had all his cameras with him; and an interpreter who asked first in a whisper, then in a loud voice, in Cantonese, wouldn’t somebody, anybody, sitting round in the street please be good enough to tell him where he could find some opium for the rich foreigners? There was plenty of opium about; we could smell it, a rich, rather pleasant and homely smell like overdone cinnamon toast for tea. But most people didn’t want to tell us any thing because of Hank’s cameras.

Hank’s cameras, although the interpreter shouted that they were not, might have been police cameras. Hong Kong is a British colony and smoking opium is illegal there as it is in Britain, only a lot more people do it. But in Hong Kong itself they do it very carefully, and mostly only in private houses. Kowloon Walled City is a little different.

Kowloon is the industrial suburb of Hong Kong with 30 miles of farming country between it and the Chinese border. The Walled City is in the middle of the rest of Kowloon and ten minutes bus ride in double-decked, scarlet London buses from the harbour. But it is unlike anywhere else in the colony. It was the old city of Kowloon – there when the British first leased the New Territories, across from the original island of Hong Kong, in 1898. The country and villages all round the Walled City became British on a 99-year lease, but the City itself was to remain Chinese territory as long as the Chinese in the city behaved themselves. In a few months the British said the Chinese were not behaving themselves, and we took over the city. But successive Chinese governments have never agreed that we had any right to do this, and both Kuomintang and the present Communists nudge us about our imperialist usurpations when they want to tease the Hong Kong government.

The result is that the Hong Kong government is shy about the city. Uniformed police do not generally go there, and most laws are not strictly enforced. The laws you are most conscious of as not being enforced are the colony’s sanitary regulations. After the broad, fairly clean streets of the Kowloon markets round the city, the city itself is filthy. The streets are so narrow that in the main ones you can stretch out your hands and touch the house walls on either side., and in the alleys you walk sideways, or move backwards in front of men carrying shoulder-yoked pails of night soil. All the streets have gutters of mixed sewage and household muck running down them. In the main street the children play in the gutter, and the grown-ups sit outside on small stools, gossiping, spitting, cleaning the vegetables for their evening meal, or just staring.

It was these people our interpreter asked about opium. After a while, a small, very thin man came up and said in English that he was from San Francisco, and he could arrange everything for us very quickly, very cheaply. Did we want to see a blue film, he said, a girlie show, or perhaps we wanted to eat dog? He meant this literally; the stew made from six-month-old Chow puppies, according to the traditional Chinese recipe, is one of the main reasons why ordinary Chinese go into the Walled City. It used to be a perfectly respectable dish in all good Hong Kong restaurants, until one day the wife of the English governor heard about it, and badgered her husband until he had dog-eating made illegal in the colony.

We said the only thing we wanted to do was to smoke opium. So the man from San Francisco, who now said his name was Joe, took us off the main street to a corner with a dentist’s sign above it. He knocked at the door and took us upstairs. The smoking room was like the others I saw later, furnished with wooden bunks built close together one above the other, and crowded with a lot of poorish-looking men, most of them gossiping gently with each other and a few reading Chinese newspapers. The atmosphere was like an eccentrically furnished and scented club.

Joe turned everybody out before we could stop him and opened a window, because, he said, the place needed some fresh air. But Hank wanted to film actual opium smoking, and he asked me to smoke a pipe or so for him. Joe showed me how to put a small wooden pillow under my neck so that I was propped up on the bunk. We were given a small pill-box of brown ointment-like opium, and Joe forced a little of it into the bowl of a miniature pipe, which I had to hold over a spirit lamp until the opium bubbled and almost melted, and then draw the smoke into my lungs in quick puffs. It was difficult to manage at first, and after I had tried four pipes, Joe took over and finished the pill-box while Hank took his film. Opium, Joe said, was not at all a good habit, but it was his habit – and his reason for leaving San Francisco. Opium, he said, had been too expensive there, ten American dollars a pipe.

In the Walled City it was very cheap. After we had finished our pill-box, we gave the man who kept the smoking room five Hong Kong dollars (about seven shillings and sixpence) because we had disturbed his customers. These men were regulars who dropped in most evenings for two, three, or four pipes, paying a few Hong Kong cents a week. The smoking-room keeper’s main expense, he said, was the 87 dollars he paid the Hong Kong police every month. It was too much, he said; and the police had wolf-hearts. He bought his opium with, he said, no trouble at all from what was smuggled into the colony. It was not, Joe said afterwards, very good opium, probably Indian grown. In fact he thought this particular smoking-room keeper mixed it with horse dung to make it go further. But anyway good opium, smuggled in from Laos and Upper Thailand, is much more difficult to get, more expensive, and mostly smoked by wealthy and fastidious men giving business parties.

Later I went back to the Walled City about four times with people who wanted to see the smoking dens. We went to different places each time, and the only time there was any difficulty about finding a place to go was when we took a Hong Kong Englishman who spoke Cantonese and wore knee-length woollen socks and white shorts. Americans and most Chinese in hot climates wear long linen trousers. Everybody in the Walled City thought the Englishman must be a police spy, and nobody would show us a smoking place until he went away.

I found that opium always had the same, most pleasant effect on me. I felt enormously self confident, very happy (like the pleasantest effects of drink) and then very hungry. I never felt at all dreamy or as if I was seeing visions, but I did feel after four pipes that I was walking six inches above the ground, and I found unexpected beauty in the rush of Kowloon traffic. The hunger never failed, and I think the enormous Chinese meals I used to eat after smoking accounted for the one time I felt slightly sick four hours later.

It is nearly two years since I last smoked, and I never felt any particular craving for opium. But if somebody offered me a pipe now, I would just as soon spend a free evening smoking as reading a woman’s magazine or going to the cinema. It can, I know, be a dangerous habit. Joe, like other strongly addicted opium smokers, was so thin that his clothes seemed to be falling off him, and smoking left him, not hungry as it left me, but unwilling and unable to eat. Another Chinese I knew in Hong Kong – American and British educated – had to get up at seven o’clock in the morning if he had a lunch engagement. He could not begin work or talk to people until he had his five hours of opium smoking first. Other opium smokers leave their jobs and spend all the money they have on their drugs. Both Singapore and Hong Kong have private temples, as well as the official British-run cures and prison hospitals where Chinese addicts can go for a voluntary cure.

On the other hand the club I stayed at in Hong Kong had an old reporter living there who could not keep his lunch engagement unless he started drinking whisky at 8 o’clock in the morning – and whisky is much more expensive than opium and seems to have a more unpleasant effect on its addicts. Also more than half my friends cannot work unless they can smoke at the same time. Opium, so the Chinese told me, does not excite people to crime, or to beat their wives or to shout. Moreover, so the educated opium addict I knew said, it does not give people lung cancer.”

A BOY’S OWN ADVENTURE

A publisher of poetry and a prolific poet and author in his own right, the British born writer Martin Booth spent most of his school years in Hong Kong, arriving as a seven year old in June 1952 after his father had been posted there to take up an administrative role in the Royal Navy.

An only child of parents whose marriage was slowly disintegrating, the young Martin was left very much to his own devices, and within weeks he was spending much of his spare time out and about on the streets of Kowloon, making friends with the local shopkeepers and rickshaw drivers, and quickly learning more than enough Cantonese to get by.

Precocious and highly inquisitive, he was soon wandering over large areas of Tsim Sha Tsui and Yau Ma Tei from his parents’ lodgings in the Four Seasons’ Hotel, but towards the end of 1953 the family was reassigned to an apartment on Boundary Street, across on the eastern side of the Kowloon peninsula.

Warned by his mother, within a few days of arriving there, that on no account was he to go near the Kowloon Walled City, Martin of course made it his business to immediately go and check out what this mysterious place might be and, over the next few months, he made several visits, being introduced to different parts of the City by two characters who befriended him there, Ho and Lau.

Returning to the UK in 1964, Martin continued to travel in Europe and the USA as well as the Far East as his literary career took off and established itself, but as he himself noted: “It had never been my intention to write an autobiography. To do so smacked of arrogance: it was not as if I were a rock star, an explorer, a footballer or a member of the miscreant aristocracy. It is true that I have had an interesting and remarkably lucky life, but that is far from unique and I never thought to document it.”

But in 2002, at the insistence of his children following the diagnosis of an especially malignant form of brain tumour, he decided he would “tackle the task” of writing about his childhood. “Once I had set out upon the task, the past began to unfold – perhaps it is better to say unravel – before me. I did have some assistance in the form of a scrapbook and several photograph albums my mother had compiled, yet these did not so much prompt as confirm certain memories, flesh out anecdotes that have spun in mind for years, rekindle lost names and put faces to them.”

The book that resulted is the highly regarded and much loved ‘Gweilo : a memoir of a Hong Kong childhood’, which he was able to complete shortly before the tumour finally claimed his life in February 2004. The following extracts recount his memories of visiting some of the more unusual places in the Walled City.

“We walked on. Suddenly, Lau stopped and said, “You no like other gweilo boy.” For the first time, he touched my hair. “Now I show you good place.”

Our destination was the balustrade building I had visited on my first excursion into the Walled City. We entered it, passed through the downstairs room, still devoid of occupants although I could hear the noise of snoring emanating from upstairs, went behind the screen, out through a door into what might have been a flagstoned courtyard and down some steps to a semi-cellar about thirty feet square. At the bottom of the steps was an old wooden door secured by a large padlock. Lau produced the key and we entered. There was a small table in the centre of the room, the walls of which were lined by benches similar to those used for gym lessons in the KJC school hall. Upon the walls hung various pennants and banners in red with serrated black borders and black writing upon them. Opposite the door was an altar bearing a small idol of a male god with a fierce-looking face, one candle alight before it.

“God Kwan Ti,” Lau explained. “This is my god.”

Yet it was something other than the banners and Kwan Ti that caught my eye. Hung between the banners were macabre, sadistically ferocious-looking weapons. One was a chain with a ball set with spikes at one end; another chain culminated in a spear-point blade. Balancing in a wooden rack were a number of metal six-pointed stars of varying diameters. From their shine, the points were clearly well sharpened.

“What is this place?” I enquired. Lau made no attempt to explain but said, “Gweilo no come here. You vew’y lucky boy I show you.”

As we moved through the big room in the building, a boy of about my age descended the stairs carrying a tray upon which there was a small lamp, several minute bowls, a number of metal needles and the most bizarre pipe. My grandfather always smoked a simple-looking Dunhill with a wooden bowl; my father, on occasion, smoked a swan-necked Meerschaum. This was very different. A good fifteen inches long, the stem was made of bamboo, the mouthpiece on milky-coloured jade or soapstone. The bowl was a curious device for it had nowhere that I could see in which to put the tobacco; indeed, it appeared to be a virtually sealed container. All there was in it was a tiny hole in the top.

“Nga pin [opium]?” I asked tentatively.

Lau stared at me. “How you know nga pin?”

“I know,” I shrugged, still not knowing exactly what it was.

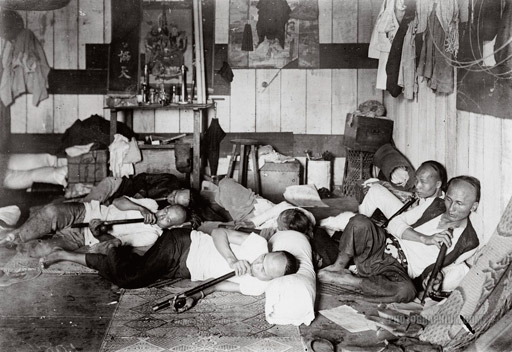

He took me by the hand and led me up the stairs. “No talk,” he whispered. As my head rose above the first-floor level, I saw half a dozen men lying on the kangs [beds]. All but one were asleep on their sides, their hands tucked between their drawn-up legs or under their necks. One snored, another intermittently moaned softly, the only other sound was their breathing. The air had a strange and familiar perfume and it was at least a minute before I recognised it as the scent of the rickshaw coolies’ pipes on my first night in Hong Kong.

The man who was awake had by his head one of the little lamps, the flame contained within a thick glass funnel. The boy moved past us, giving me a quick and puzzled look. He went to the man and impaled a small bead of something on one of the needles, starting to revolve it in the lamp flame: then, very adroitly, he placed it over the tiny hole in the pipe bowl, passing it to the man who lay on his side and sucked evenly on the pipe. After doing this three times, the man lay down and closed his eyes. The boy removed the pipe and blew out the lamp.

“We go,” Lau murmured. Once we were outside, I asked, “what was that man doing?” “He smoke opium,” Lau answered. “Get dream, go good time-side.”

I stepped over the characteristic high lintel to find myself in a small entrance hall. To one side, seated at a tiny desk, was an old woman. Lau greeted her and they spoke in quiet voices until Lau stepped aside to reveal my presence. The moment she saw me, the woman cackled asthmatically and entered into a conversation with Lau that was filled with much suppressed hilarity and sidelong glances at me.

Feeling I was being made the butt of their humour, and not quite knowing how to react, I looked down. It was then I saw the old woman’s feet projecting out from under the desk. They were minute, encased in scuffed brocade slippers no bigger than a baby’s knitted bootees. The toe end was squared off like the ballet dancing pumps girls wore at school.

“Lotus foot,” Lau said, following my line of sight. “Long time before, China-side, men say tiny foot on lady ve’y . . .” he paused, searching for a word “. . . booty full. Like lotus flower.” I nodded sagely but could not see how, with the wildest imagination, a foot could resemble a flower.

After the obligatory caress of my golden hair by the old woman Lau led me down a corridor of dark wooden panelling, passing a number of narrow doors split like those of a stable. At intervals, dim bulbs provided the minimum of light. Towards the end of the passage-way, Lau stopped at a door and knocked. The top half opened and a pretty Chinese woman looked out. She wore an imperial yellow silk cheongsam, her hair piled up and held in place by a soapstone pin. As they spoke in subdued voices, she did not take her eyes off me for an instant. Needless to say, she reached out to touch my head.

There was the sound of a pulling bolt and the bottom half of the door opened to reveal a panelled cubicle lit by a red lamp in front of a tiny shrine. The only furniture was a wide kang raised higher than normal from the floor and a Chinese-style chair. Upon the kang were a tangle of quilts and a Chinese paperback book on the cover of which were portrayed a man and a woman kissing. On a shelf below the shrine was a row of Chinese scent bottles. “You go in,” Lau instructed. “Sit down.”

I perched on the rim of the kang. The young woman sat next to me, talking to Lau through the door but all the while watching me. The air – and the young woman – smelt of orange blossom slightly tainted with sweat.

“You know this place?” Lau enquired at length. “No know,” I admitted. “This old place,” Lau continued. “Maybe more one hundred year. Long time before place for rich man come jig-a-jig. Fam’us place. Man come long way from Canton jig-a-jig here. Fam’us girl stayed here long time before.” To lend meaning to his words, he put his thumb between his index and middle finger and wiggled it. The young woman giggled. I was lost as to its meaning. “You lo know jig-a-jig?” Lau asked. I shook my head. “Lo ploblum,” he replied dismissively. “Come! We go now.” He said goodbye to the young woman. I added my own choi kin. She burst into a peal of giggles, put her hand demurely to her mouth to stifle them and closed the doors on us.

Whenever I visited Kowloon Walled City, Lau was always there, ready to guide me around, drink tea with me and talk. When, after a few months, the place started to lose its appeal and I stopped visiting. I never saw him again. It was some years before I realised that he and Ho had been Triad members – Chinese Mafiosi – infamous for their utter ruthlessness, whose secret fraternity ran the opium dens and brothels, and held Kowloon Walled City in its thrall. The semi-subterranean room had been their meeting place.

THE WICKEDEST CITY

Searching through the numerous files to be found in Hong Kong’s Public Records Office, either real or on microfilm, that refer to the Walled City can easily become addictive. Every folder seemed to turn up some fascinating detail or, as in this case, a long lost article that probably hasn’t seen the light of day in over 50 years.

Written by a young American journalist, Cathie Breslin, and published in the Toronto-based magazine The Daily Star in November 1963, the article recounted Breslin’s visit to the Walled City in search of an opium den. Raised in Massachusetts, the daughter of a pediatrician, Breslin had graduated from the University of Toronto in 1957 as a history and philosophy major before opting to try her hand as a journalist.

Horrified by, in her own words, the “sexual ghetto” of Canadian journalism at that time, where she was “flung onto the women’s pages”, Breslin decided to go freelance, working in Canada and the USA for a few years before leaving for Southeast Asia in 1961. She was to remain there for the next two years, travelling round the whole region including Vietnam, saying later that, “the war at that time was almost fun … Vietnam wasn’t really cranked up yet.” This was clearly no ordinary young American ingénue.

Entering the Walled City with Chinese photographer Eddie Chan, they met an opium addict they refer to in the article as Cheng who agreed to help them on their quest, taking them to his home while he made the necessary arrangements:

“Cheng’s smooth, boyish face belies 40 troubled years. A former Nationalist policeman turned narcotics hustler, he has worked ‘in this business’ since coming to Hong Kong 14 years ago. His job entails sizeable risk, but only pays 80 cents a day. Plus 16 cents for ‘lunch’.

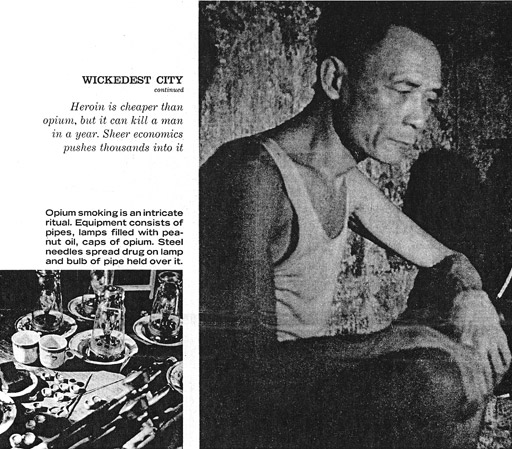

An hour later Cheng went off to fetch the opium. His plump, pretty wife arrived home with her two small sons. Cheng returned with a friend, Lai, their arms loaded with newspaper-wrapped bundles, and ordered his wife and children into the alley. He had bought a new $5 pipe for the occasion – so cheaply made that he had to bind it together with a strip of silk. He complained that they don’t make them now the way they did in ‘the old days’, when opium represented gracious living in China.

The pipe assembled and the peanut-oil lamp lit, Cheng grabbed two large cans to serve as pillows. He and Lai stretched out on the linoleum bed and began the intricate rite: they sizzled the ‘cooked’ opium on top of the lamp, smeared it on the rim of the pipe’s rubber bowl and scraped off the blistered ash. The babble from the alley seemed to fade as Lai took whistling pulls on the pipe.

Since coming to Hong Kong I had wanted to try this forbidden ritual. I tapped Eddie on the shoulder: ‘Can I try a puff?’ Startled, he translated. Cheng scrambled off the bed and gave me his place and pipe. ‘What do I do now?’ I asked Eddie. ‘Just smoke it like a cigarette.’ Although I smoke I don’t inhale. When my big moment came I drew in mightily; I seemed to be pulling smoke to the bottom of my lungs. I went dizzy from sheer effort.

If everybody got as little a kick as I did from an opium smoke, Hong Kong would have an enormous problem solved. Government surveys reveal that the majority of Hong Kong’s estimated quarter-million narcotics addicts are middle-aged, low-salaried workers looking for relief from the ‘stresses of their everyday lives’. Lai is typical. An ex-fruit peddler, he has smoked for 15 years. He stopped once when he realised it was killing him, but a stomach ailment drove him to start again. ‘When I smoke,’ he says, ‘I feel no more pain and I can smile again.’ Now unemployed, he hires himself out to tend the pipes of more affluent smokers and smokes up their leftovers.”

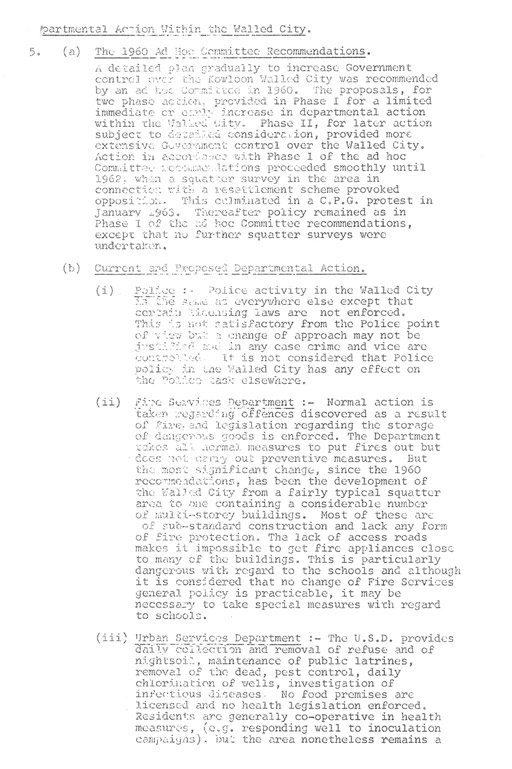

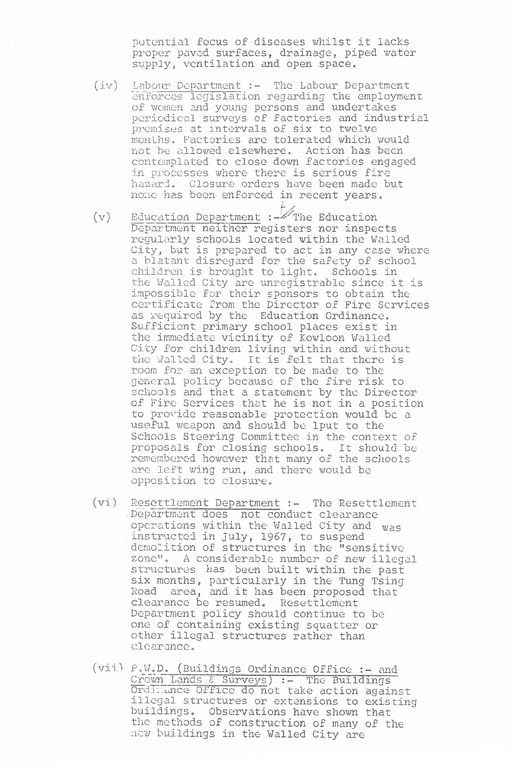

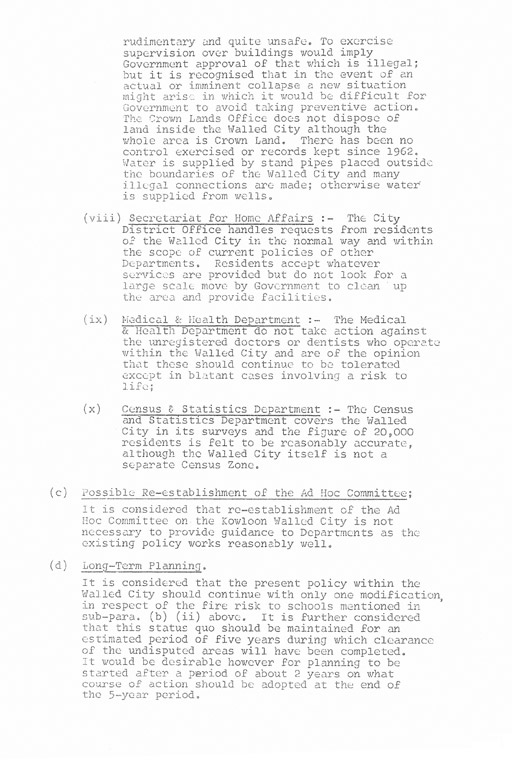

AN UNEASY ALLIANCE

Orange Urban Services refuse bins were located around the City and collected nightly.

The idea that to enter the Walled City was to enter a totally different world where all the norms and regulations of ordinary urban life were entirely absent is deep-rooted and almost impossible to shake. To this day, many people believe that the police never went there, or that if they did it was in only in groups of 40 or more. And against this background, it seems inconceivable that any of the other government departments would have had any sort of involvement at all with the City.

But as the official document below shows, nothing could be further from the truth. The City could not have survived for long without the modern conveniences that the rest of us take for granted – notably electricity and a safe water supply, but there were a whole host of other less noticeable incursions by the authorities that helped keep the City running safely and, more or less, efficiently.

A CLINIC FOR HEROIN

In the process of putting this new edition together we have interviewed a number of policeman who patrolled in the Walled City from as far back as the 1960s right up to the City’s clearance in the early 1990s. Their testimony has been enlightening and puts quite a different perspective on just how lawless or otherwise the City might have been at different times in its development.

Indeed, all of those we interviewed were keen to emphasise that, from the early 1960 onwards at least, the City was little different to other working class areas of Hong Kong. We are only sorry that we haven’t been able to track down any police officers who may have patrolled there in the 1950s, when by all accounts the Walled City really did live up to its reputation. If anyone reading this does know of such a person, we would love to hear from them. See BE INVOLVED under ‘The Book’ section for contact details.

None of this is to say that the Walled City didn’t have its moments and one of the more unusual stories that came to light while talking to one particular policeman who served there in the late 1970s was his memories of what he described as heroin clinics. The timing is important, as this occurred just a few years after the formation of the ICAC (the Independent Commission Against Corruption), which had clamped down heavily on both the Triad’s operations and corruption in the police force.

This resulted in the Walled City becoming once more an important centre for drug dealing. Such activity had never been eradicated from the City. Indeed, it was one of the few places where the very worst addicts could eke out some sort of existence without too much interference. The ordinary residents didn’t particularly approve of their presence, but for the most part they were ignored. In this, the City was not alone and there were several other locations in Hong Kong well known to the police where such activity went on.

In the late 1970s, however, there was a noticeable rise in drug dealing that the police were keen to bring under control. The problem, as always, was catching drug dealers in the act. The few entrances into the City made it impossible to enter without being spotted, and once inside it was all too easy for the perpetrators to disappear into the maze of alleys and stairways. Not so the addicts, however, who became an important source of information for the police when planning future operations.

There was one important catch however: addicts could only be arrested and taken in for questioning if they were actually caught carrying drugs. Being an addict alone was not enough. Aware of this the Triad operators, safe in the knowledge that the Walled City provided ideal cover, came up with the simple plan of rather than just selling addicts small packets of heroin, they would spread the word and open a temporary ‘clinic’ where the addicts could queue for their ‘shot’ and then leave, carrying nothing.

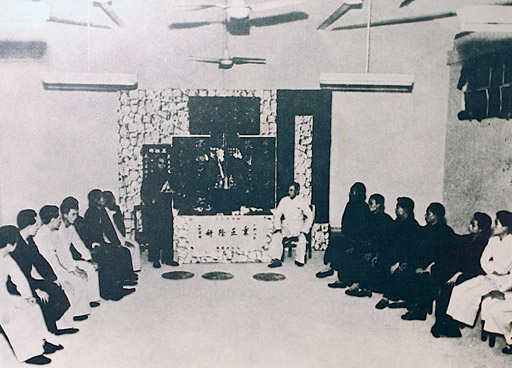

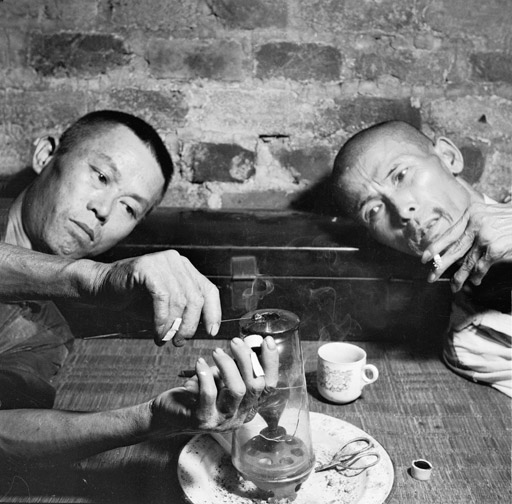

By the time the police realised what was going on and had gathered in sufficient numbers to carry out a raid, those involved had almost invariably left the scene. The two photographs shown here were taken from surrounding roofs as part of a surveillance operation and show a clinic in action (above), as well some of the lookouts (below) guarding one of the nearby alleys.

As an interesting aside, it is important to note that police raids of this sort were almost always carried out in sufficient numbers to ensure that as many of the escape routes could be covered as possible. As such, their presence was far more noticeable than the ordinary two-man foot patrols – whose presence was so common as to be unremarked upon – and one can only speculate if this is what led many to believe that the police only entered the Walled City in large numbers. This, it seems, is how myths are born.

A LEGEND IS BORN

An opium den in Hong Kong in the 1950s.

The failed attempt to clear the Walled City of squatters in 1947 left the Hong Kong authorities in a quandary. Before the War the Hong Kong government had felt they could act with impunity, actually evicting several pig farmers from the City’s confines in the 1930s. The Kuomintang government had raised its objections, but the situation in China was so confused that the powers to be in Hong Kong felt these could be safely ignored.

By 1947 this was no longer the case. The severe deprivations Hong Kong had experienced during the War had taken their toll and the ease with which the Japanese had been able to occupy the city in 1941 had shaken the authorities’ confidence. The situation in China was also changing rapidly, with Mao Tse Tung and his communist forces on the rise, though what his intentions might be, in particular with regard to Hong Kong, remained a mystery.

The flood of refugees into the territory through 1948 and 1949 was soon giving the Hong Kong government more to worry about than the Walled City, but until the situation in China had resolved itself they had already decided that caution was the better part of valour and that no further action would be taken in the Walled City that might cause the authorities in China to object. And when this came down to the issue of dual jurisdiction, this would include police activities there and, more importantly, prosecution of those who broke the law.

The Hong Kong authorities were keenly aware that if they attempted to prosecute anyone arrested for a crime within the City, this potentially opened the door for the Chinese government to step in and claim equal rights, possibly demanding that a Chinese court be set up inside the City. It is doubtful this was on the Chinese government’s mind at the time, but the decision was made that for the time being at least no-one arrested in the City would be charged with any form of criminal offence.

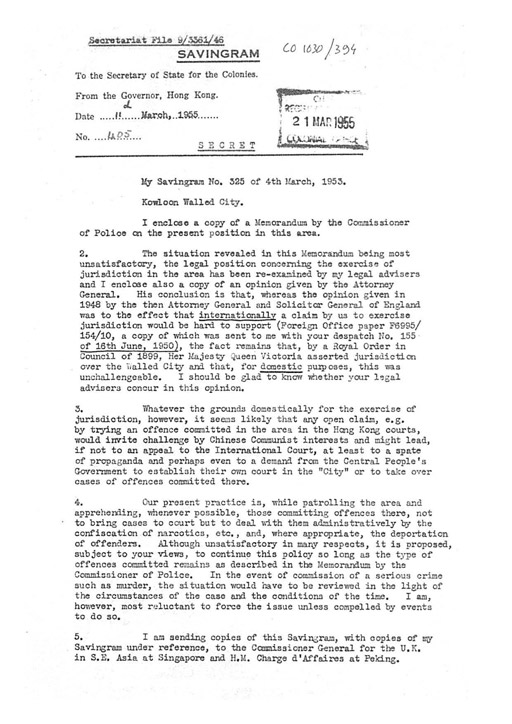

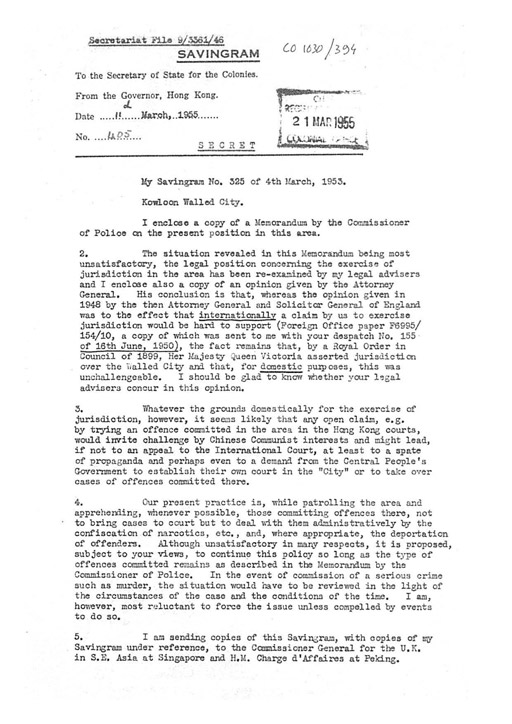

Covering letter to the 1955 report, detailing the concerns about taking Walled City residents to court.

The police would continue to patrol the area and arrests would be made, but apart from a night or two in the cells and the confiscation of illegal materials, most notably drugs and drug paraphernalia, no further action would be taken. Some minor cases were prosecuted through the civil courts and the most serious offenders, usually known Triad bosses, were repatriated to China, but otherwise the Walled City’s residents were largely left to their own devices. Unsurprisingly, this state of affairs did not go unnoticed and soon Triad gangs were flocking to the City, keen to set up any illegal operation they could think of.

Covering letter to the 1955 report, detailing the concerns about taking Walled City residents to court.

The police would continue to patrol the area and arrests would be made, but apart from a night or two in the cells and the confiscation of illegal materials, most notably drugs and drug paraphernalia, no further action would be taken. Some minor cases were prosecuted through the civil courts and the most serious offenders, usually known Triad bosses, were repatriated to China, but otherwise the Walled City’s residents were largely left to their own devices. Unsurprisingly, this state of affairs did not go unnoticed and soon Triad gangs were flocking to the City, keen to set up any illegal operation they could think of.

Unlike their mafia and camorra counterparts in the West, the Triads have no real central structure and for the most part are made up of a loose alliance of individual street gangs that claim allegiance to one Triad or another. Power within the Walled City was split roughly between the 14K and Sun Yee On factions which, when they were not fighting each other, tended to be involved mainly in low-level criminal enterprises, notably protection rackets, control of the sex industries and ‘street-corner’ drug dealing.

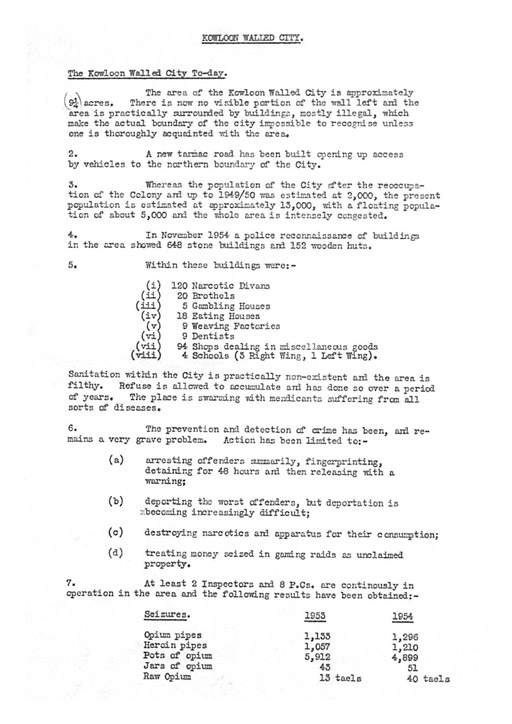

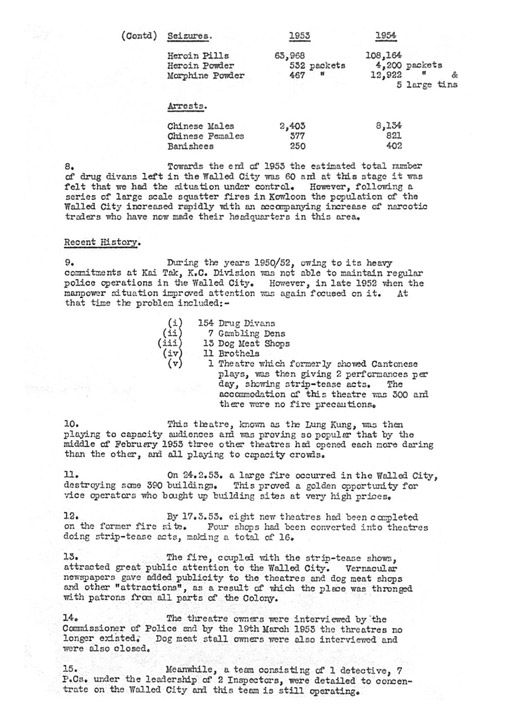

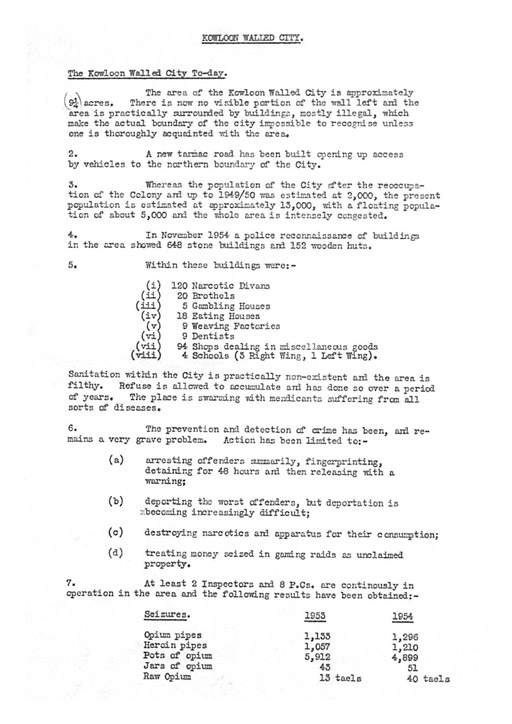

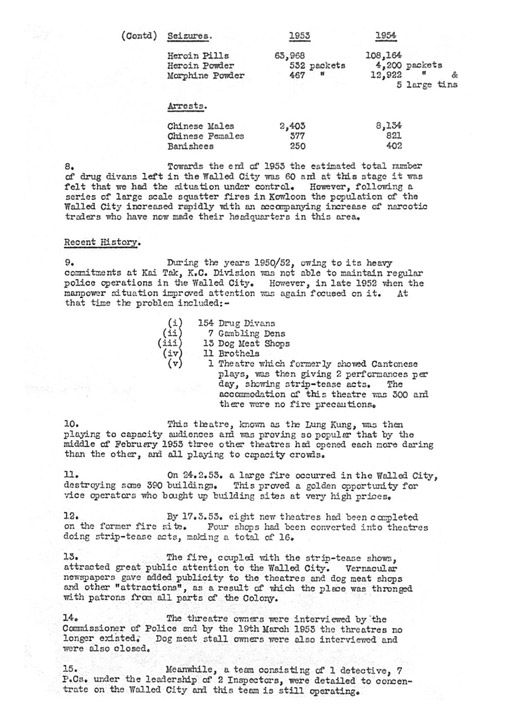

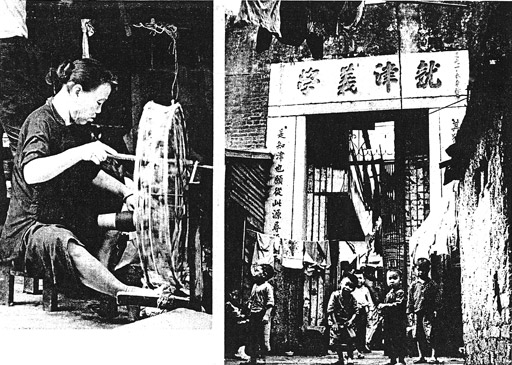

With the minimum of police interference, such activities boomed, with one police report, drawn up in 1955 in response to questions raised by the Foreign Office in London, noting the presence as early as 1952 of 154 drug divans, seven gambling dens, 13 dog meat shops, 11 brothels and one theatre giving two striptease performances per day. If nothing else, not only does the report confirm that the police were patrolling the City, but more importantly that they had a pretty detailed knowledge of what was happening there.

And indeed attempts were made to try and bring the situation under control, but the maze-like layout of the City, an alert band of lookouts and, no doubt, tip-offs from within the police force itself, meant large-scale raids almost always arrived too late after most of the participants had left, leaving only a smattering of comatose opium addicts and a few older prostitutes who were too slow on their feet. Drugs and the apparatus of opium smoking were confiscated and certain properties were closed, but the Triads considered this a small price to pay and operations could always continue in another location almost without a break.

The 1955 police report gives an unrivalled glimpse of what life was like in the Walled City at the time.

And so the situation continued. By the nature of the times, too, in some quarters the Walled City took on an almost glamorous quality, with the film stars of the time arriving in smart cars which were left parked on Tung Tau Tsuen Road while their occupants disappeared into the City to taste dog meat or other delights. The Triads also proved adept at adapting to prevailing trends. The same 1955 report notes a sudden surge in striptease parlours when the Walled City started becoming a recognised stop for Japanese sex tourists keen to see what Hong Kong had to offer.

The 1955 police report gives an unrivalled glimpse of what life was like in the Walled City at the time.

And so the situation continued. By the nature of the times, too, in some quarters the Walled City took on an almost glamorous quality, with the film stars of the time arriving in smart cars which were left parked on Tung Tau Tsuen Road while their occupants disappeared into the City to taste dog meat or other delights. The Triads also proved adept at adapting to prevailing trends. The same 1955 report notes a sudden surge in striptease parlours when the Walled City started becoming a recognised stop for Japanese sex tourists keen to see what Hong Kong had to offer.

But the times were changing and the heyday of Triad control in the Walled City was soon on the wane. And not so much because the police were managing to gain a degree of control, but rather because corruption within the police force was becoming so endemic that the Triad gangs no longer needed to hide away in Hong Kong’s darker corners, but rather could operate in the open in the parts of town where more money could be made. There would still be some crime in the Walled City – sometimes more, sometimes less – but the total freedom that the Triads had enjoyed there for that brief period would never be matched.

SETTING THE SCENE

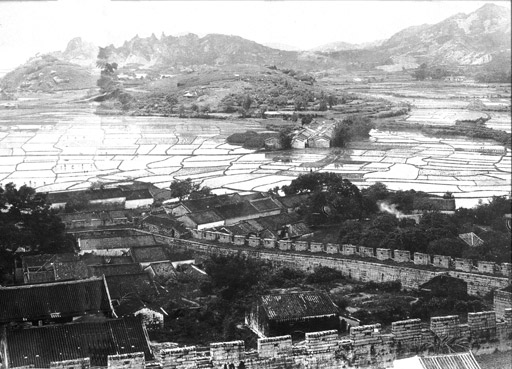

The Walled City seen from White Crane Hill in 1865.

The root of the Walled City’s curious legal status can be traced back to the 1898 Treaty of Peking that ceded the land that came to be known as the New Territories to the British on a 99-year lease. From the Chinese perspective, this was yet another unequal treaty that was being forced upon them, but they were unwilling to give in without a fight and they demanded that the military and magistrate’s compound, known in English rather misleadingly as Kowloon Walled City, which stood at the foot of White Crane Hill overlooking Kowloon Bay and neighbouring Kowloon City should remain Chinese Territory.

Rather grudgingly the British, wanting to settle the matter as quickly as possible, agreed to include a clause stating that “within the city of Kowloon, the Chinese officials now stationed there shall continue to exercise jurisdiction except so far as may be inconsistent with the military requirement to the defence of Hong Kong”. It was a gloriously vague phrase and within a year, when the Chinese garrison in the Walled City was reinforced by a further 600 troops in response to fierce resistance to British rule in the New Territories, the Hong Kong government decided enough was enough and marched on the City only to find it already deserted. To validate the situation, an Order-in-Council was issued in December 1899, announcing British jurisdiction over the Walled City, but as a unilateral revision to the Treaty it was never recognised by the Chinese.

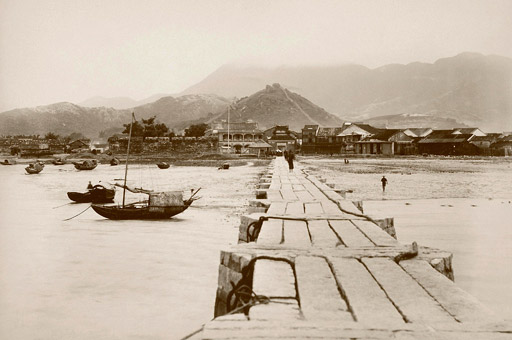

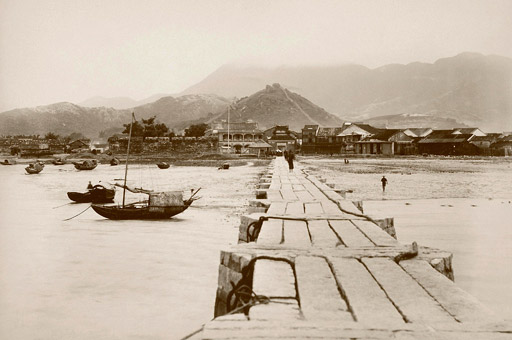

Lung Chun Pier and the ceremonial entrance to Kowloon City in 1898.

In reality, little of this mattered. The Walled City was now a deserted compound deep in the New Territories’ countryside, then a long way from the built-up areas to the south on the Kowloon Peninsula. And with the Chinese government largely in turmoil over the next 40 years, the Hong Kong authorities felt they could do with the Walled City as they wished, to the extent that in the 1930s they evicted the pig farmers who had taken the place over and turned it into a tourist spot. But all was about to change.

Lung Chun Pier and the ceremonial entrance to Kowloon City in 1898.

In reality, little of this mattered. The Walled City was now a deserted compound deep in the New Territories’ countryside, then a long way from the built-up areas to the south on the Kowloon Peninsula. And with the Chinese government largely in turmoil over the next 40 years, the Hong Kong authorities felt they could do with the Walled City as they wished, to the extent that in the 1930s they evicted the pig farmers who had taken the place over and turned it into a tourist spot. But all was about to change.

The Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in December 1941 and the subsequent occupation, unsurprisingly, affected all of Hong Kong badly, but the impact was especially notable around Kowloon City. The part of Kowloon Bay which Kowloon City once overlooked had been reclaimed in 1923 as part of a failed business venture, the Hong Kong government taking back control of the land in 1925 and establishing Kai Tak Airport. Expansion of the airport in the 1930s had begun to change the area, but when the Japanese took over Kai Tak as its military airfield in 1941, the rate of change escalated rapidly.

The Walled City and Kowloon City in 1924, shortly after completion of the reclamation that was to become Kai Tak Airport.

A good part of old Kowloon City overlooking the airport was demolished and the walls of the Walled City were torn down for use as building material during the airport’s subsequent expansion. Allied bombing caused yet more damage, virtually obliterating what was left of old Kowloon City, though somehow sparing the few old Walled City buildings that still existed. And so it remained, the rubble left by the fighting providing handy building material as those Hong Kong residents displaced during the War began to return to Hong Kong at the end of 1945, quickly followed by the first of the refugees fleeing the civil war in China.

The Walled City and Kowloon City in 1924, shortly after completion of the reclamation that was to become Kai Tak Airport.

A good part of old Kowloon City overlooking the airport was demolished and the walls of the Walled City were torn down for use as building material during the airport’s subsequent expansion. Allied bombing caused yet more damage, virtually obliterating what was left of old Kowloon City, though somehow sparing the few old Walled City buildings that still existed. And so it remained, the rubble left by the fighting providing handy building material as those Hong Kong residents displaced during the War began to return to Hong Kong at the end of 1945, quickly followed by the first of the refugees fleeing the civil war in China.

The situation for the Hong Kong authorities was now extremely complicated. Efforts were made to start rebuilding Kowloon City in a new area to the west of its old location, around a grid of streets that remain to this day, but the demand for shelter far outstripped supply and squatter settlements began to spring up all over the hills at the back of Kowloon and more importantly around and within Kowloon Walled City.

Fearing they might lose control of the area, in 1947 the authorities took the unprecedented step of trying to deter building on the Walled City site itself and evict those who had already moved into the area, but the operation was badly handled, resulting in significant resistance. More importantly, it also provoked rioting across the border in Canton (Guangzhou), with the British Mission there being set on fire. The Chinese government voiced it strongest objection to this unwanted action on Chinese soil, and the Hong Kong authorities were forced to withdraw its plans and leave the City to its own devices.

Despite the 1899 Order-in-Council claiming British jurisdiction over the area, it was clear that the Walled City would henceforward be subject to dual jurisdiction, with all the uncertainties and restrictions that would entail. Even so, few at that time could imagine just how quickly this situation would take over every aspect of the Walled City’s growth and development in the years to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!