Binondo Heritage Tour

As perpetual travelers, unwilling to miss any of the sights, we’ve got used to read up on what is there to see in places we would be visiting including its history. So here is about Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown.

We can trace Binondo’s history to the 9th century, when Chinese traders would sail to Maynilad from Cathay, where their vessels dropped loads of valuable merchandise like silk and pottery and returned laden with sugarcane, hemp, coconuts, and other local products. But the mass migration of the Chinese to Manila began in the 16th century when the Philippines was already the colonial capital of Spain in Asia.

Alarmed with the rapid swell of the Chinese immigrants and the Sinophobia (fear of Chinese) set off by the Limahong invasion and the murder ofGovernor Gomez Perez Dasmariñas, the Spanish colonial government decided to restrict them to a ghetto.

But why did the Spaniards keep the Chinese in the colony despite of the risks of insurgence? Because they needed the skills and expertise of the Chinese as painters, scribes, tailors, carpenters, masons, smiths, butchers, cooks, printers, and accountants in developing the new colony.

The Chinese ghetto that became known as Parian first took shape on the bank of the Pasig where the Chinese traders did business. This colony was later moved in Intramuros, near the convent of the Dominicans, who had been in-charged of converting the Chinese. The Parian was moved some ten times from the Walled City to Ermita to the island across the Pasig from Intramuros called the Isla de Minondoc.

On March 28, 1594, the adjoining island of Minondoc was annexed to the village of Baybay or what is now the San Nicholas District. The island’s original owners, Don Antonio Velada and his wife Doña Sebastiana del Valle sold it to Governor General Luis Perez Dasmariñas (son of the slain governor), which he donated to the Christian Chinese community. This land-grant for a Chinese colony reserved strictly for Chinese Christians was to become the Arrabal of Binondo, which in two centuries would become the richest town in the Philippines.

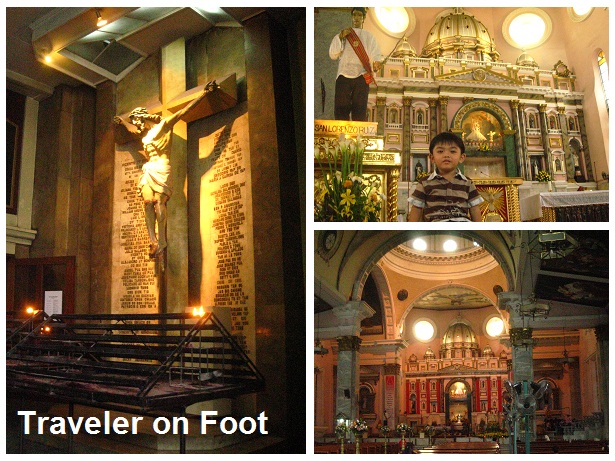

By the 1640s, Binondo boasted of a stone church with 50 large windows and adorned with elaborate tapestries and paintings. This church was destroyed during the British Invasion but was rebuilt in greater splendor as its residents, a mix of native and Chinesemestizaje, grew in wealth. Its annual fiesta on the last Sunday of October in honor of its patroness, theNuestra Señora del Santo Rosario, was said to rival the grandeur of Intramuros’ La Naval in olden days.

The current Baroque church was rebuilt from World War II-ruins and has been re-dedicated to the first Filipino saint, San Lorenzo Ruiz, who served as an altar boy before being martyred at Nagasaki in 1637.

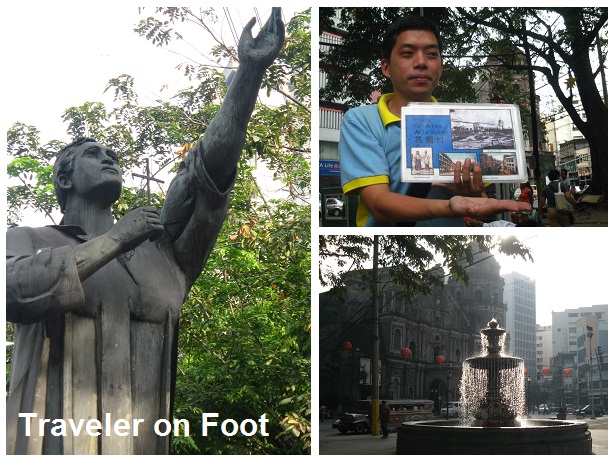

Across Binondo Church is Plaza Calderon de la Barca, which was one of the most impressive open spaces in old Manila. It was named as Plaza de Binondo, then Plaza Carlos IV, before it was named after the Spanish playwright, and later as Plaza San Lorenzo Ruiz, whose statue dramatically stand on the plaza.

The Chinese called it Hue Heng Khao or at the foot of the garden because the plaza was lined with plants and trees with Baroque fountains at either ends. The Binondo Church, Hotel de Oriente, and La Insular Cigar Factory were the plaza’s principal landmarks before World War II.

The street at the right side of the church was formerly called Sacristia, after the sacristy entrance of the church. In 1915, it was renamed in honor of businessman and philanthropist Don Roman Ongpin. His bronze monument at the entrance of the street serves as reminder of his patriotic role in Propaganda Movement and the first Filipino to wear a barong tagalog during public occasions.

The kilometer-stretch of Ongpin Street is lined with restaurants, cafes, apothecaries, curio shops, jewelry stores and goldsmith, and religious shrines. One side street shrine is dedicated to the miraculousSto. Cristo de Longos.

One of Binondo’s legends revolves around the venerated image of the Santo Cristo de Longos. The story goes that a deaf-mute Chinese miraculously regained his speech when he accidentally found the blacked image of the crucified Christ at the site of an old well in the barrio of Longos.

The cross was installed at the Church of San Gabriel where it became an object of devotion among the people of Binondo. The image was transferred to Binondo Church where it is enshrined to this day on a glass-covered niche near the side entrance of the church. Another shrine located in San Nicholas district was built on the site of the old well where the miraculous image of Christ was found.

But there is another shrine of the Sto. Cristo de Longos tucked in one of Ongpin’s side streets where devotees come to make offerings and burn joss sticks in a manner seen mostly in Buddhist temples to a large crucifix covered with leis of sampaguita.

This is what we like best in Binondo, the happy blending of East and West.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!