Why the Chinese won’t smile at strangers

Irecently watched the first episode of Ricky Gervais’ “An Idiot Abroad” (Jan 2011), in which he sends his reluctant and culturally clueless friend Karl to China. In utter culture shock on his first day in China, he takes a rickshaw ride through Beijing’s busy Houhai Lake area.

Irecently watched the first episode of Ricky Gervais’ “An Idiot Abroad” (Jan 2011), in which he sends his reluctant and culturally clueless friend Karl to China. In utter culture shock on his first day in China, he takes a rickshaw ride through Beijing’s busy Houhai Lake area.

One thing that freaked him out was the fact that he would make eye contact, smile and say “hello” to passing Chinese…but not a single person responded or smiled back (instead staring back with confused looks).

Echoing the feeling of many first-time travelers to China, he mutters, “I don’t think I’ve ever felt this lost before.”

Like Karl, many Westerners have a hard time adjusting to this seemingly cold behavior. Indeed, it’s easy for the first time visitor to China to label the Chinese as unfriendly, or worse, rude (by their cultural standards anyway). But don’t be offended—it’s not you. The Chinese generally don’t smile at any strangers—foreign or Chinese.

IN AND OUT GROUPS

Blame it on Confucius (again). As I described in my Confucius 101 article, his teachings emphasis family bonds and nurturing your own web of relationships (guanxi).

Blame it on Confucius (again). As I described in my Confucius 101 article, his teachings emphasis family bonds and nurturing your own web of relationships (guanxi).

One result is that the Chinese—consciously or otherwise—see the world in terms of two groups of people: Their own circle of relationships on one side, and everyone else on the other. In other words, they have a much stronger distinction between “In” versus “Out” groups.

This helps explain why the Chinese tend to view the solo traveler with a combination of curiosity, pity, and even envy. For the average Chinese person, traveling alone to a foreign country is perhaps the most unsettling and terrifying experience that they can imagine.

They feel vulnerable without their support group—it’s just bunch of Others who they can’t necessarily trust (and who don’t speak Chinese)!

They feel vulnerable without their support group—it’s just bunch of Others who they can’t necessarily trust (and who don’t speak Chinese)!

Since I exclusively travel by myself, I’ve heard it all. While they don’t usually say that they feel sorry for me, I can see it in their eyes. They can’t wrap their heads around why someone would want to take a vacation to a foreign country by himself.

In fact, many are even reluctant to travel alone in their own country. In his book, China Road, the author tells of a time when he was haggling to hire a taxi to take him on a long-distance trip through a neighboring province that was much poorer. He said that most drivers were afraid to drive through without bringing a Chinese friend for added protection. It turned out that the drivers weren’t afraid of bandits. Instead were worried about the local police, who often pulled over drivers from richer provinces (by license plate) in order to extort expensive “fines” out of them! But with the added safety of a friend as a witness, it’s much harder for them to pull any dirty tricks.

TRIBE MENTALITY (or “Us versus Them”)

As I described in my Confucius 101 article, Chinese society has always had a strong focus on the family (as well as those in their guanxi network). On the flip side, however, the Chinese tend to be indifferent—suspicious or sometimes hostile even—towards strangers and those outside their network.

As I described in my Confucius 101 article, Chinese society has always had a strong focus on the family (as well as those in their guanxi network). On the flip side, however, the Chinese tend to be indifferent—suspicious or sometimes hostile even—towards strangers and those outside their network.

And throughout China’s long history, this was probably the smartest thing to do. I imagine that there must have been many thieves and con men who traveled around pulling scams and robbing overly-trusting country bumpkins.

What’s more, there was certainly no shortage of suffering throughout Chinese history (conflict, famine, natural disaster, cruel emperors, etc). When faced with this survival-of-the-fittest mode, kindness towards strangers tends to takes a back-seat to taking care of your own.

What’s more, there was certainly no shortage of suffering throughout Chinese history (conflict, famine, natural disaster, cruel emperors, etc). When faced with this survival-of-the-fittest mode, kindness towards strangers tends to takes a back-seat to taking care of your own.

Even as recently as a generation ago—during the dark Mao days—the Chinese learned to survive by sticking together. This often meant being indifferent to the suffering of the anonymous masses pleading for help.

WHY ARE THE CHINESE SO “RUDE”?

One negative consequence of this In-Out group mindset is that many Chinese feel no obligation to treat strangers with the level of respect that Westerners take for granted. As explained in my article on Chinese etiquette, the first-time visitor is typically hit with an ice-cold bucket of culture shock. Foreigners are often unsettled—and flat-out pissed off at times—especially in the rough and tumble urban environment where patience is NOT a virtue.

[ Click here for Spitting, Slurping, and Queue-busting: China Mike's Chinese Etiquette Tips for Travelers ]

My point is that, the average Chinese person who you meet on the street can seem cold and unfriendly. Bus driver and other civil servants in the cities who deal with the public on a daily basis can be especially dismissive and unhelpful (even abusive). Try not to take it personally.

Now I’m not trying to justify all these behaviors by saying that they’re just “cultural differences”. Sometimes rude behavior is just rude, regardless of culture. Instead of rationalizing, I’m simply helping you understand the roots of this behavior.

From the Chinese point of view, Western behavior and attitudes towards strangers is equally as puzzling. Many Chinese who spend time studying or working in the U.S. return home and report that “Americans treat strangers like family, and treat their family like strangers.”

On the other hand, I’ve been told by many that they deeply admire the openness and kindness of Americans; they often lament the fact that Chinese society lacks a similar level of openness and trust.

BUT DON’T LET ME STOP YOU FROM SMILING AT STRANGERS…

In any case, I hope to give you a better understanding of why the Chinese don’t smile at strangers, and other seemingly rude behavior.

For instance, many visitors are appalled by the way that the average Chinese person treats service people. Westerners are taught to treat everyone with common courtesy. However, you generally won’t see the average Chinese customer giving smiling eye contact to their waitress, for example. Instead, they seem to bark orders in a manner befitting that of a spoiled emperor.

So I’m not telling you to cut out the smiling bit. Many appreciate it, especially those who used to dealing with foreigners. Instead, I’m telling you not to be offended when you only get back a blank stare. The Chinese just aren’t used to strangers smiling, waving, or saying “hello” out of the blue.

Instead, their confused heads are probably trying to figure out why this grinning Laowai is talking to them in the first place (“What is this fool up to? Is he mistaking me for someone else? Do we all really look the same? Oh no, maybe I met him from before! Why the hell do these big-nosed round eyes all look same?! Damn, I wish I had my camera!”).

Instead, their confused heads are probably trying to figure out why this grinning Laowai is talking to them in the first place (“What is this fool up to? Is he mistaking me for someone else? Do we all really look the same? Oh no, maybe I met him from before! Why the hell do these big-nosed round eyes all look same?! Damn, I wish I had my camera!”).NOT IN MY BACKYARD (Anywhere else is fine though)

A related societal downside to this Us versus Them mindset is that feelings of social and civic responsibility are somewhat lacking in Chinese culture. Many expats and longer-term residents complain that the Chinese have a “Not in my backyard” view of the world. The general attitude is “It doesn’t affect me or my family so why should I care?”

I remember reading a story told by an expat who was buying something on the street with his expat friend. There was a near-accident that somehow caused a manhole to come free. Everyone on the street watched as other cars almost got into accidents as they swerved to avoid the hole. Finally, the two expats walked over and replaced the manhole. When they returned, the vendor said that no Chinese would’ve gone to the trouble to do what they did.

Littering is another visible example of this behavior. To be fair, societal behaviors don’t change overnight (as a kid, I remember when littering was much more common before that crying Indian commercial).

Littering is another visible example of this behavior. To be fair, societal behaviors don’t change overnight (as a kid, I remember when littering was much more common before that crying Indian commercial).

People in most developing countries, such as India and China, are vigorous litterers–even in otherwise beautiful places like the beach. In China, I think the problem is partly due to the attitude is that someone is being paid for cleaning up (which is true). I can’t say the same for India, where trash would often pile up randomly on the street.

At times, this not-in-my-backyard attitude is humorous (to me anyway). For instance, in China, many even litter in their own building—in common areas, like the lobby and hallways (sometimes you’ll see huge red stains in stairwells from betel nut, a kind of Asian chewing tobacco). The attitude is as long as the trash isn’t literally inside my house, I don’t a shitake. Similarly, you might notice store owners diligently sweeping trash in front of their own store…and on to the street, just a few feet away.

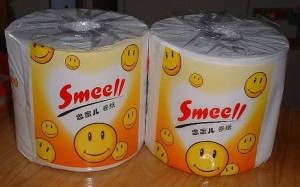

This also helps explain why Chinese public toilets never have toilet paper. In the same episode of “An Idiot Abroad,” the clueless traveler is dumbfounded because he assumes that Chinese people don’t use toilet paper after they drop a deuce.

This also helps explain why Chinese public toilets never have toilet paper. In the same episode of “An Idiot Abroad,” the clueless traveler is dumbfounded because he assumes that Chinese people don’t use toilet paper after they drop a deuce.

What he didn’t know was that the Chinese just accept that they have to B.Y.O.T.P. (because there’s always some jackass who will steal the whole roll). Which is not surprising given China’s huge poor population (mostly stuck in a survival mentality), combined with this lack of civic responsibility.

[ Click here for my Funny Chinese Counterfeit Brands slideshow ]

THE LAOWAI: THE ULTIMATE OUTSIDER

For the foreign traveler to China, this Us versus Them mindset is a bit of a double edged sword. On the one hand, the laowai is the “ultimate outsider”—there’s little chance that the average Chinese person will discover that this foreigners is related to them somehow.

For the foreign traveler to China, this Us versus Them mindset is a bit of a double edged sword. On the one hand, the laowai is the “ultimate outsider”—there’s little chance that the average Chinese person will discover that this foreigners is related to them somehow.

So for some Chinese—for instance taxi drivers or other service people—they’ll blatantly ignore foreigners, especially if they’ve had past experiences going around in frustrating circles trying to communicate with foreigners.

Worse, the foreign tourist is also more susceptible to Chinese con-artists. As I describe in my Avoiding Chinese Scams article, scammers often learn English just so that they can target foreigners. Scamming Chinese tourists is much harder, since they are slow to trust strangers (and usually not dumb enough to follow a stranger to some unfamiliar place). Because of this in-out group mindset, the Chinese also don’t feel guilty about walking away, or even completely ignoring someone who approaches them on the street.

On the other hand, con artists quickly learn that foreigners don’t want to be “rude” to a stranger. They’re more open– delighted even–to having a “genuine” encounter with a new Chinese friend (who curiously seems to really want to practice English or check out some tea ceremony).

[ Click here for Why You Should Never Take a Black Taxi: China Mike's guide to Avoiding Chinese Scams for Tourists ]

But there are also upsides to be the ultimate outsider. In some ways, being a foreigner makes you more approachable to some Chinese. Chinese people assume that foreigners are pretty much all clueless on the unspoken rules of Chinese etiquette and social distance. And that’s exactly why some are more open to strike up a conversation, especially if the want to try out their English (I’m talking about normal, friendly Chinese, not scammers!).

In fact, once the initial ice is broken, many will be exceedingly friendly and generous—inviting you to visit their home towns and wanting to exchange email and IM addresses (which to me, is odd since there’s barely any face-to-face communication going on in the first place).

In fact, once the initial ice is broken, many will be exceedingly friendly and generous—inviting you to visit their home towns and wanting to exchange email and IM addresses (which to me, is odd since there’s barely any face-to-face communication going on in the first place).

Similarly, many Chinese want to be helpful and friendly to foreigners as a point of national pride. They’re proud of their country—they often feel that China gets a bad rap in the global media and so want to be good ambassadors. Just don’t let your new friend take you to any tea ceremonies…..

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!