Former Senior Mountie: Carney’s RCMP–Chinese Police Cooperation Deal Is a Counterintelligence Danger That Kills Sovereignty

Canadian police tradecraft is valuable to a state that blends criminal, intelligence, and political objectives seamlessly.

OTTAWA — After nearly five decades in policing, intelligence, and financial-crime investigations—including professional experience working in Asia—I have learned a simple rule: who you cooperate with matters as much as what you cooperate on.

Last week, the Prime Minister’s Office announced that Canada and the People’s Republic of China will enhance law enforcement cooperation on drug trafficking, transnational and cybercrime, and money laundering. On paper, this sounds reasonable. Fentanyl is devastating communities. Cybercrime drains billions. Organized crime adapts faster than borders.

But experience teaches me that cooperation with the PRC is never just technical, never apolitical, and never insulated from the priorities of the Chinese Communist Party. Canadians deserve to understand the risks.

In Canada, policing is constrained by courts, disclosure rules, independent prosecutors, and an entrenched—if imperfect—commitment to individual rights. In the PRC, law enforcement is an extension of state security. Its primary function is not public safety as Canadians understand it, but regime stability.

During my work in Asia, this distinction was never subtle. Human rights, due process, and judicial independence were not guiding principles; they were obstacles to be managed. Criminal labels—fraud, subversion, cybercrime, economic offences—were routinely applied to political, ethnic, or commercial targets when it suited the state.

This matters because when Canada “cooperates” with such a system, we are not dealing with an equal partner operating under comparable legal and ethical constraints.

Modern law enforcement cooperation hinges on information: identifiers, financial trails, travel histories, digital footprints, investigative techniques. Even limited disclosures can be powerful when combined with the PRC’s vast domestic surveillance and data-collection apparatus.

What concerns me is not a single file transfer, but cumulative exposure. Over time, cooperation can reveal:

how Canadian agencies prioritize targets,

how we detect money laundering or cyber intrusions,

what thresholds trigger investigations.

That knowledge is valuable—not just to criminals, but to a state that blends criminal, intelligence, and political objectives seamlessly.

This is not an abstract debate. Canadians of Chinese, Uyghur, Tibetan, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese heritage have already reported intimidation, monitoring, and coercion linked to PRC interests. Cooperation frameworks risk legitimizing or facilitating such pressure under the guise of criminal enforcement.

From experience, I can say this is how it often unfolds:

Political or activist activity is reframed as fraud, extremism, or cybercrime.

Information obtained abroad is used to pressure family members back home.

Fear spreads, and communities disengage from Canadian police—making everyone less safe.

If cooperation deepens without hard safeguards, Canada risks exporting vulnerability rather than security.

Yes, China is part of global supply chains for synthetic drugs and financial flows. But cooperation cuts both ways. Sharing cybercrime or laundering typologies exposes investigative methods and blind spots. Joint cyber efforts risk blurring lines between criminal disruption and state-enabled cyber activity—lines that are already thin.

In my career, liaison relationships were among the most effective intelligence-collection tools I encountered—not because people were reckless, but because trust and “professional courtesy” erode caution over time.

I am not arguing for isolation or naïveté. International crime demands international engagement. But experience—earned the hard way—tells me that authoritarian systems do not compartmentalize. If Canada does not set firm, public, and enforceable limits, cooperation will drift toward outcomes we neither intend nor control.

Before this partnership deepens, Canadians should demand:

absolute restrictions on sharing information about Canadians and residents,

clear human-rights and transnational-repression safeguards,

independent oversight and transparency,

and a willingness to suspend cooperation when abuse risks emerge.

For nearly fifty years, I worked within systems designed—however imperfectly—to balance security and liberty. In Asia, I saw what happens when that balance does not exist. The PRC has shown repeatedly that human rights, rule of law, and individual protection are subordinate to state power.

Cooperating with Beijing may promise short-term gains against crime. The long-term cost—measured in compromised methods, intimidated communities, and eroded sovereignty—could be far higher.

Canadians should not mistake a press release for a safeguard.

This latest installment in Safeguard Defenders’ Investigations series takes a deep dive into the Chinese police’s expanding global policing toolkit by examining a seemingly recent campaign to counter transnational telecom and online fraud (according to the official provincial statements) by several provinces in the People’s Republic of China.

This latest installment in Safeguard Defenders’ Investigations series takes a deep dive into the Chinese police’s expanding global policing toolkit by examining a seemingly recent campaign to counter transnational telecom and online fraud (according to the official provincial statements) by several provinces in the People’s Republic of China.

This investigation, although short at merely 20 pages, is packed with five major revelations:

- Established Nine forbidden countries, where Chinese nationals are no longer allowed to live unless they have “good reason”;

- New tools for “persuasion” operations laid down on paper, including denying the target’s children in China the right to education, and other limitations on family members, punishing those without suspicion of any wrongdoing by “guilt by association” (similar to the North Korean practice), and

- It also includes government documents stating relatives in China that do not help police "persuade" targets should be investigated and punished by either police or the internal Party police the CCDI;

- The establishment of at least 54 police-run “overseas police service centers” across five continents, some of which are implicated in collaborating with Chinese police in carrying out policing operations on foreign soil (including in Spain).

Download the full investigation - (PDF) for further information, data, maps, tables, and sources.

For this overseas operation, rather than using international police or judicial cooperation mechanisms – which provide for control mechanisms to protect the rights of the target, including the right to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence prior to judgment – official provincial statements and guidelines from the local Ministries of Public Security or Procuratorates highlight the mass use of *persuasion to return* methods.

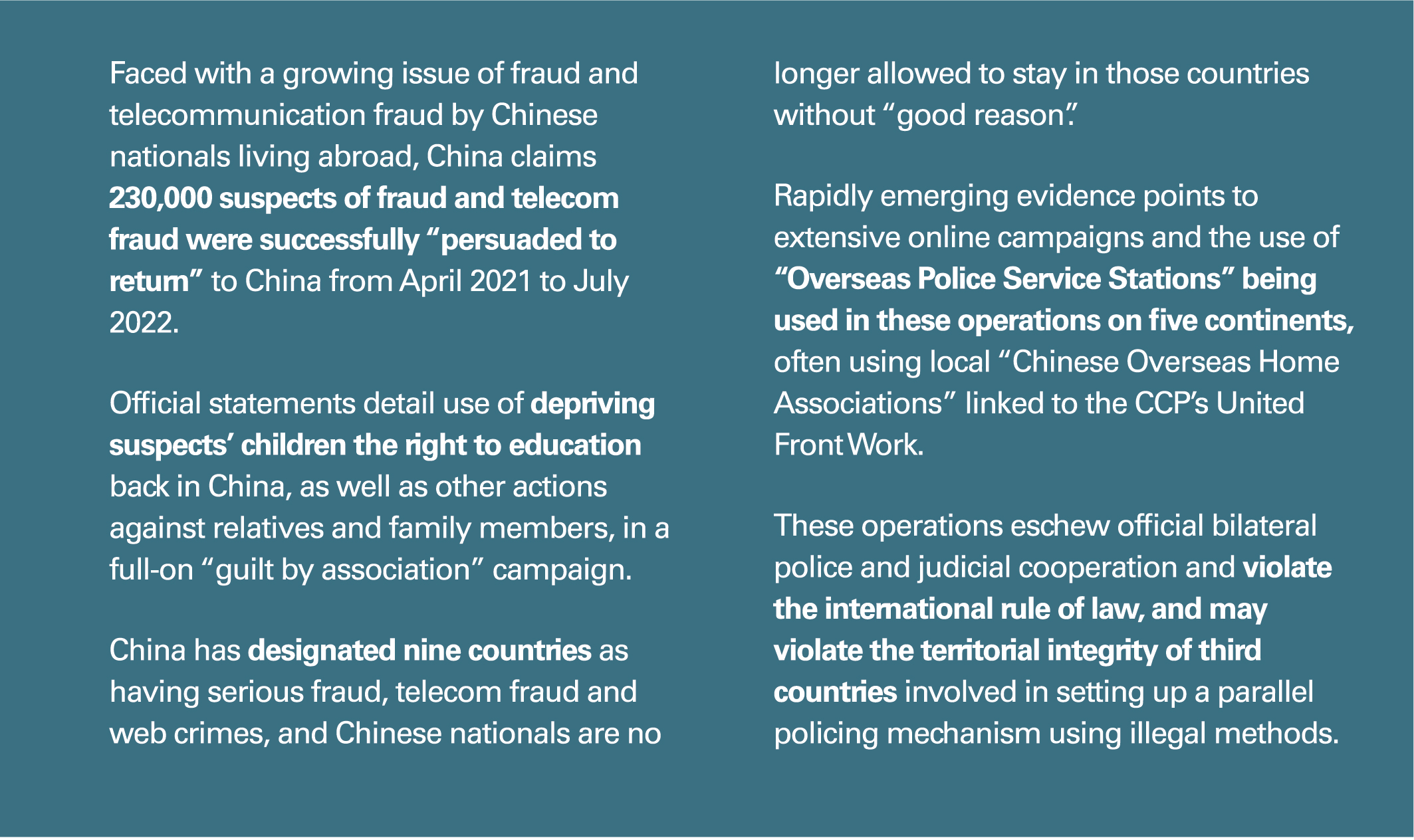

According to such statements, in the mere fifteen months between April 2021 and July 2022 alone – and pandemic restrictions notwithstanding -, a staggering number of 230,000 Chinese nationals were returned to face potential criminal charges in China through these methods, which often include threats and harassment to family members back home or directly to the target abroad either through online or physical means.

October 29: The current investigation (PDF) is a revised, correcting minor errors, in particular one related to Yunnan police and cross-border issues with North Myanmar and the anti-fraud campaign overseas and its linkage to a pilot project launched across 10 provinces. Errors first identified courtesy of Jeremy Daum.

110 Overseas - Chinese Transnational Policing Gone Wild traces the origins of the campaign conducted by ten “pilot provinces” back to 2018. Official guidelines explicitly outline the different tools made available to "persuade" the targets to voluntarily return to China to face charges. These include targeting the purported suspects' children in China, denying them the right to education, as well as targeting family members and relatives in a similar fashion. In short, a full-on "guilt by association" punishment to "encourage" suspects to return from abroad.

The tools and aims of these methods were amply described in Safeguard Defenders’ January 2022 report Involuntary Returns, which examined higher-value target operations Sky Net (and Fox Hunt).

The very recent documentation presented in this investigation indicates their increased use in operations abroad also by local Chinese police and judicial authorities, confirming a very dangerous trend.

The combination of an absolute absence of minimal judicial safeguards for the target and the association by guilt methods employed on their families, as well as the illegal methods adopted to circumvent official international cooperation mechanisms and the use of United Front Work-related organizations abroad to aid in such efforts, pose a most grave risk to the international rule of law and territorial sovereignty.

Download the full investigation (PDF) for further information, data, maps, tables and sources.

Learn more about "persuasion to return" methods in Safeguard Defenders' report Involuntary Returns, where “persuasion” operations are classified as IR Type 1 (and occasionally Type 2) operations.

On 2 September 2022, a national Anti-Telecom and Online Fraud Law was adopted, establishing a claim of extraterritorial jurisdiction over all Chinese nationals worldwide when pursuing fraud, telecom- and online fraud.

Nine forbidden countries

The designation of “nine forbidden countries” for Chinese citizens to travel to or reside in under a local emergency notice within the campaign, show the extreme lengths the authorities will go to in their crackdown and the ease by which a citizen might find him- or herself a suspect. The regulation treats everyone as a suspect until proven innocent.

One police officer publicly stated that even though not all Chinese living in northern Myanmar are criminals, they would still be subject to "persuasion to return" operations. Police further admitted they did not actually have evidence that all those targeted had committed any crimes.

While there is no official breakdown of where the 230,000 individuals were returned form, a majority appear to hail from the nine “forbidden” countries, with Myanmar standing out at 54,000 returned between January and September 2021.

In more recent months, evidence suggests the “success” of the pilot campaign is rapidly leading to its expansion on a truly global scale.

110 Overseas

Over the course of the past year further evidence emerged indicating at least two of the county police jurisdictions as active in this long-arm policing operation through the establishment of “overseas police service stations” in cooperation with local Hometown Associations linked to United Front Work.

The United Front system (United Front Work) is the work of Chinese Communist Party agencies seeking to co-opt and influence ‘representative figures’ and groups inside and outside China, with a particular focus on religious, ethnic minority and diaspora communities. - Alex Joske

The overseas service stations are primarily set up to conduct a series of seemingly administrative tasks to aid overseas Chinese in their community of residence abroad, but they also serve a far more sinister and wholly illegal purpose. While the evidence available so far suggests most transnational policing operations are carried out through the online tools of the domestically operated “overseas station”, some official anecdotes of official operations explicitly cite the active involvement of the Hometown Associations on the ground in tracking and pursuing targets indicated by the local Public Security Bureau or Procuratorate in China.

On 23 May 2019, People's Public Security News published the article《探索爱侨护侨助侨机制,设立警侨驿站海外服务中心 青田警方积极打造“枫桥经验”海外版》on the Qingtian County Public Security Bureau’s “innovative set up of Overseas Police Service Centers” providing “convenient services for the vast number of overseas Chinese” in a cited 21 cities in 15 countries, including Rome, Milan, Paris, Vienna, Austria, etc., “hiring 135 Qingtian-born overseas Chinese leaders and leaders of overseas Chinese groups” and “establishing a team of more than 1,000 overseas grid service information personnel”, coordinated by a “domestic liaison center”.

"Through the establishment of overseas service centers, Qingtian County Police has made breakthroughs in its overseas pursuit of fugitives. Since 2018, the Qingtian police have detected and solved six criminal cases related to overseas Chinese, successfully arrested a red notice fugitive, and persuaded two suspects to surrender under the assistance from the Overseas centers.”

At least two such cases took place on European soil: according to Chinese State media accounts, overseas police service stations actively assisted the Chinese police in “persuasion to return” activities in Spain and Serbia.

Based on open-source information collected so far, 54 physical “overseas service stations" have been identified in 30 countries across five continents. As these only represent the stations set up by Fuzhou and Qingtian Counties, the total number is most likely higher.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!