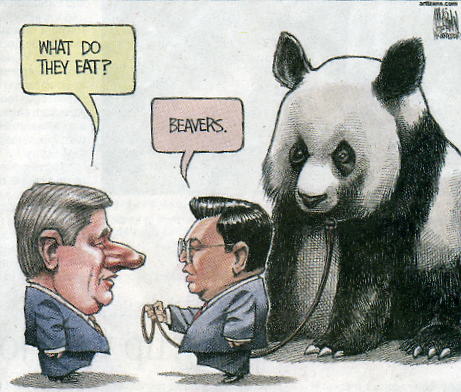

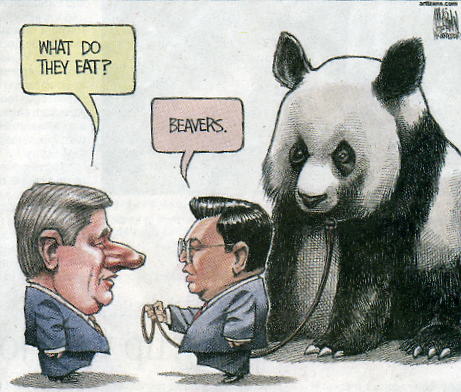

Puppets of Beijing

An aggressively pro-China policy can only hurt Canada's national interests. So who's pulling the strings in Ottawa's scheme to build up the next Communist superpower?

Kevin Steel - May 30, 2005

Norm Altenhof is in love. The 63-year-old retired 9-1-1 operator and former air force veteran from Calgary returned April 20 from a month-long tour of China bursting with enthusiasm. "I would go back there in second," Altenhof says. "Standing on a street corner in Beijing is just like being in Toronto, only it's cleaner." Everywhere he went, there were outward signs that a country that had been a hermit nation barely a few decades ago had blossomed into a first-world economic miracle. There were boutiques full of Gucci shoes and businessmen in flashy BMWs. After touring nine Chinese cities, and visiting the homes of Chinese nationals of varying economic stations, Altenhof is convinced that the People's Republic of China is a nation to watch in the 21st century. "Everybody was pretty upbeat and looking to the future. They seemed to really embrace capitalism," he says, though he admits he only got a tourist's eye view of things.

It's true that nobody would talk politics in public places, Altenhof admits. Especially not about the 1989 massacre of pro-democracy students in Tiananmen Square, which is never discussed openly in Beijing--though, in private, some citizens told him that the actual number of murdered students was 3,000, not the 1,000 widely reported in the West. And there were signs of a growing disparity between the rich and the poor, says Altenhof. Despite aggressive economic reforms over the past decade--including the partial privatization of state-owned firms and even the creation of a national stock exchange--it's estimated that out of the 1.3 billion people living in China, only 250 million--about one in six--have benefited economically.

Altenhof believes that what's still missing are democratic reforms. He says that he was thrilled, for instance, to see Conservative MP Jason Kenney, on an official government visit to Beijing earlier this year, demonstrate his support for China's underground pro-democracy movement by paying a visit to the family of Zhao Ziyang. Zhao, a former premier of China who had implemented many of the sweeping reforms, had been excommunicated from the Communist party after expressing sympathy for the Tiannanmen protestors. He spent his final days as a pariah, and, after he died in January, Kenney personally paid tribute to Zhao by visiting his home. "If people like that can keep the pressure on Beijing, then I think everything will be OK," says Altenhof.

But that kind of pressure on Beijing is exactly what Canada's government seems desperate to avoid. Prime Minister Paul Martin castigated Kenney for his visit, claiming that he himself had chosen not to pay tribute to Zhao because the family had requested privacy--which was later proven to be false. During the January visit, Martin himself faced a barrage of criticism from human rights groups for refusing to put much pressure on his hosts over their notorious human rights abuses. He didn't even protest when the Communist party banned certain Chinese-Canadian journalists from covering Martin's visit because they had been critical of the state in the past.

"Paul Martin's opposition of a visit to the family of a deceased leader of a democratic movement within China is entirely in keeping with Paul Martin's China policy in general," says Alastair Gordon, president of the Canadian Coalition for Democracies based in Toronto. If anything, says Gordon, Martin has taken pains to coddle the Communists. "He is submitting to the will of Beijing when he denies the right of any democratically elected Taiwanese to even set foot in Canada to visit family or in transit to some other destination," says Gordon. "He submits to the will of China when he refuses to treat the Dalai Lama as a political leader, only as a religious leader, and refuses to speak about human rights with him. He is submitting to somebody's will when he approves $50 million in foreign aid to a country that has a gross domestic product of $7.4 trillion, the world's largest army, its own space program, and 700 missiles aimed at Taiwan." The fact that Canada is sending millions in relief to an undemocratic country with the fastest-growing economy on the planet--and successfully launched its first space mission in 2003--does seem odd when you consider that, on April 19, Minister of International Co-operation Aileen Carroll announced that foreign aid is being given on the basis of need and good governance.

But Martin had more pressing matters to discuss with China's Communist rulers than to nag them about executed dissidents, persecuted Christians or the systematic obliteration of Tibetan culture. There was a little matter of oil. Or rather, the big matter of oil. Before leaving Beijing, Martin had inked a multilateral trade agreement that promised the Chinese government even more kindness from Canada, specifically greater co-operation in several industries, but with an emphasis on oil and gas. "Canada and China have decided to work together to promote cooperation in the oil and gas sector, including Canada's oil sands, as well as in the uranium resources field," read a press release from the Prime Minister's office announcing the agreement. "Canada and China will therefore encourage Canadian and Chinese enterprises to develop mutually beneficial commercial partnerships in these sector" With its explosive growth--by 2020, China's GDP is expected to quadruple from its 2000 level--the Red state is thirstier than ever for resources. Across the globe, the Communist government is fanning out and buying up any available precious metals and crude oil it can lay its hands on. China now consumes about 4.956-million barrels of oil a day (about a quarter of the 19-million barrels Americans guzzle daily), with about a quarter of it imported. But economists estimate that by 2030, oil consumption in China will quadruple, far outstripping domestic production. In addition to cutting deals in oil-rich countries, such as Venezuela, Sudan and Iran, the Chinese are aware of the potential of the Alberta oilsands.

The People's Republic of China has already secured a foothold in the northern Alberta oilfields. There's Husky Energy Inc., controlled by Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing's Hutchison Whampoa group, which recently announced it is going ahead with a $10- billion oilsands development project scheduled to be in full production by 2009. Around the same time, a new pipeline should be complete, to deliver all that oil through the Rockies to the B.C. coast, where it can be loaded onto tankers for export. The project, announced April 14, is a joint venture between Canada's largest pipeline builder, Enbridge Inc., and one of the PRC's major oil producers, Petrochina. CNOOC Ltd., another massive state-owned Chinese oil producer, made its first foray into the oilsands in April, scooping up a 17 per cent stake in Calgary-based MEG Energy Corp.

But given that Canada is situated right next to the largest energy market in the world--and the Americans are interested in the oilsands as a secure source for crude, one that comes with a lot fewer complications than relying on Mideast suppliers--some are wondering why we're so anxious to let the Chinese lock up so much of the reserves. The Communists, after all, are in the midst of an unprecedented military buildup, they're still one of the worst human rights abusers on the planet and they seem increasingly willing to draw the U.S. into a war over Taiwan if that country ever declares independence (a move that President George W. Bush has indicated he will defend).

So, what exactly is Canada's interest in providing fuel to a country that may soon represent a bigger threat to world stability than Iran or North Korea? "We're left with a foreign policy toward China that absolutely defies explanation as to how it's in regional interests, trade interests, political interests, economic interests, Canadian interests," says Gordon. Though he does think there's one explanation, unpleasant as it may be: that the politicians who devise Canadian foreign policy have their own reasons for getting close to China. "The kind of connection between those who make our China policy show that they have the potential to benefit by submitting to the will of Beijing."

Long before average Canadians like Altenhof caught on to the potential of China, Paul Martin was getting in on the ground floor. Back in the days of Chairman Mao, when China's economy was still heavily agrarian and backwardly collectivist, the future prime minister was already planting the seeds of commerce. "I first came to China in 1972, during the waning years of the Cultural Revolution. I was in business then," Martin said, in a Jan. 21 speech in Beijing. At the time, the aspiring businessman was working for Power Corporation of Canada, a firm with $16 billion in revenues controlled by Montreal's powerful Desmarais family. It was clearly an eye-opening experience because he's been making deals in China ever since. Canada Steamship Lines, the gargantuan shipping company Martin purchased from Power Corp. in the eighties, that is now run by his children, has taken advantage of China's cheap workers to build ships. Three CSL container ships were built in the Jiangnan Shipyard, controlled by the People's Liberation Army. A fourth was refurbished in Shanghai. Martin actually owns 35 per cent of China's Tangshan Jinshan Marine Co.

The Chinese interests of the Desmarais family--who have been strong financial backers of Martin's political campaigns from early in his political career--run even deeper. Power's chairman, Paul Desmarais, is the founding chairman of the Canada China Business Council, which promotes trade between the two nations. The honorary chairman is his brother, Andr? Desmarais, CEO of Power. Power Corp. has longstanding ties with one of the PRC's leading corporations, CITIC Group. As Andr? remarked at a general meeting in May 2000, "Shareholders are aware through our annual reports that for over 20 years we have had a relationship with the state-owned China International Trust and Investment Corp. of Beijing." In 1997, the relationship culminated in Power paying $358 million for a four per cent interest in the Hong Kong firm, whose interests include coal-fired power-generation facilities, automobile and food distribution concerns, hotels, shopping malls, infrastructure, and communications firms. Their primary business is in aerospace, owning a major stake in Cathay Pacific airlines and manufacturing fighter jets for the People's Liberation Army.

With a direct stake in such a broad swath of China's economy, the Desmarais surely stand to benefit from Canada's increasingly cozy relationship with the Communists in Beijing. But it's not just Martin they have to thank. It was his predecessor, Jean Chr?tien, under whom Ottawa took a distinct pro-Beijing turn. Andr? Desmarais, who sits on the board of directors of CITIC Pacific Ltd., a CITIC subsidiary, is married to Chr?tien's daughter, France. And it was in the same year that Chr?tien's son-in-law was negotiating the major investment in CITIC that Canada, for the first time in six years, withdrew its support for a UN resolution censuring China over its abysmal human rights record. Today, China is still cited by groups such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International as a major abuser of human rights, including its jailing of political opponents, persecution of religious groups and its population control measures, which include forced abortions.

But 1997 was a pivotal year for Sino-Canadian relations in other ways. It was that year that a group of investigators with the RCMP and CSIS wrapped up a probe into the systematic infiltration of Canadian society by Chinese gangs. It was dubbed Operation Sidewinder. But almost immediately after the security report that followed, titled "Chinese Intelligence Services and Triads Financial Links in Canada," was completed, CSIS ordered it destroyed. At the time, the head of CSIS was Ward Elcock. Elcock, in fact, is the nephew of Michael Pitfield, a confidant of former prime minister Pierre Trudeau. Pitfield co-authored the report in the early eighties that led to the creation of CSIS. Today, he is a director of Power Corp.

CSIS officials would later claim the report was destroyed because it was full of fantastical conspiracy theories. But they not only eradicated the report itself--CSIS took the unusual step of ordering all notes pertaining to the report shredded. In 1999, someone leaked one of the few surviving copies of Sidewinder to the press. The revelations were explosive: the security agents had found that PRC operatives had managed to infiltrate key sectors of the Canadian economy. Through their association and, in many cases, investments in property, technology firms and security, the spies had managed to cultivate influence in Canadian politics and our economy, while harvesting valuable information from our industries and military. One of the companies prominently identified in Sidewinder was none other than CITIC, which had invested hundreds of millions of dollars in Canadian real estate and resource companies. Sidewinder also noted that caches of arms had turned up on Canadian Indian reserves that had been manufactured by a CITIC subsidiary. Meanwhile, China's state-owned shipping firm COSCO had made the port of Vancouver its main shipping hubs. Reports from U.S. intelligence show COSCO ships have smuggled arms into the U.S., North Korea, Pakistan and Iran.

Brian McAdam, a former foreign service bureaucrat who ran Canada's immigration office in Hong Kong from 1968 to 1971, and again from 1989 to 1993, was one of the key figures whose suspicions about the PRC's infiltration of Canada led to the Sidewinder investigations. He says that in the eighties, as the Chinese takeover of Hong Kong in 1997 began to draw near, the Communists in Beijing struck a deal with the powerful Hong Kong triads--criminal organizations specializing in the international smuggling of drugs, weapons and humans. The government and the gangs would work together to exploit the West for mutual advantage. One of the primary strategies was to curry favour and influence with political leaders through large campaign donations. "They are very good at talent spotting," McAdam says, noting that Chinese agents were donating to Bill Clinton's campaigns while he was still governor of Arkansas.

In fact, the same sort of so-called conspiracy theories that characterized Sidewinder were unearthed in an American investigation into Chinese influence peddling and intelligence gathering in that country. In 1999, the Chinagate scandal rocked the Clinton presidency, when it emerged that the president had accepted large campaign contributions throughout the nineties directly or indirectly from Chinese intelligence agents. What followed, under Clinton, was a U.S. foreign policy adjusted in a way that made it easier for the Communists to get their hands on leading military technology. Defence contractors were permitted to work closely with the PLA to help advance its missile capabilities. What the Chinese couldn't get legally, they stole through a series of front companies based in the U.S. and Canada.

Detailed in an investigation headed by U.S. Representative Christopher Cox, the 1999 scandal was partly overshadowed by the disclosure of then president Bill Clinton's affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, and few took notice, especially here in Canada. But many of the same figures that were identified in the Cox report were the same ones fingered by Sidewinder. Both look into the connections of Li Ka-shing, who, in addition to his Husky holdings, has invested millions in Canadian properties, banks and telecom firms. Also making appearances in both the U.S. and Canadian reports are Macau gambling magnate Stanley Ho, COSCO and CITIC, which was caught making illegal contributions to Clinton's campaign.

Al Santoli, director of the Asia America Initiative and a former national security advisor in the U.S. Congress, says the Sidewinder report made a big impact in the States. "It got people to look at what was developing here in the U.S.," he says. "It was something that was systematic. It had a pattern to it. And because of the deft knowledge of the authors--and a few other reports that were coming out at that time--it drew an expanded light on what was going," Santoli says, adding that the Canadian intelligence underlined the extent to which political systems and electoral processes were being subverted. "Sidewinder put it in a contextual pattern and that was very important."

Had CSIS had its way, those details might never have come to light.

The agency's unorthodox attempts to suppress the report eventually resulted in an investigation in 2003 by Canada's Security Intelligence Review Committee, the public body that oversees CSIS. Shortly afterward, the investigation was quietly abandoned.

Coincidentally, there were several members of the SIRC board who themselves were linked to some of the names that popped up in the Sidewinder report. Former Ontario premier Bob Rae also sat on the SIRC board. Rae's brother, John, is an executive and director at Power Corp. (with its stake in CITIC). The SIRC board was headed by Paule Gauthier, who up until her first appointment to SIRC, in 1995, had spent 25 years as the corporate secretary of Power Communications, a Power subsidiary. Power Corp's links to CITIC are mentioned in the Sidewinder report, under "Case Studies."

Exactly how much influence the Chinese nationals named in Sidewinder managed to procure in Canada remains uncertain; the probe was originally intended to be a starting point to stimulate further investigation. What is known is that Li Ka-shing has been a supporter of Martin's, with Husky donating $10,000 to the prime minister's leadership campaign in 2003 and another $10,000 from Li-controlled firm Concord Pacific Group Inc. (Li, who is one of the most powerful men in Asia, has said the accusations that he is working for the Communists are nonsense.) According to documents obtained through the Access to Information Act, Martin had several meetings with Li Ka-shing during a 1995 trip to Hong Kong when he was still finance minister. The substance of those meetings however, remains a mystery, as nearly every detail in the minutes of the meeting relating to Li has been blacked out by the government, with notes indicating that the information was highly sensitive and pertained to national security. In other words, Li, a foreign national, was privy to a meeting where things were discussed that are now considered too sensitive for Canadian citizens to hear. Meanwhile Li, whose companies make up an estimated 15 per cent of the capitalization of the Hong Kong stock exchange, is alleged, in intelligence documents, to work closely with the Chinese government. According to the Sidewinder report: "On 23 May, 1982, Li Ka-shing and [Triad boss] Henry Fok met with [PRC leaders] Deng Xiaoping and Zhao Ziyang in Beijing to discuss the future of the peninsula. Their task would be to advise and educate the Chinese authorities on the basic rules of capitalism. In return, Beijing would give them privileged access to the Chinese economic basin."

Martin's predecessor, Jean Chretien, who was prime minister at the time Sidewinder was ordered suppressed, has links to Li as well. While on one of his few hiatuses from politics, between 1986 and 1990, Chr?tien sat on the board of Gordon Capital--a company run by Li Ka-shing's son, Richard Li--and personally brokered deals between Gordon Capital and Power Corp. The investment bank became the focus of mini-scandal in 1995, when Gordon won the federal contract to take Petro-Canada public, shocking the Bay Street business community, which expected the multimillion-dollar deal would go to a larger, more experienced Canadian firm.

At the time Martin was with Power Corp., he got his start working for Maurice Strong. Strong, the former head of PetroCanada, who remains a senior adviser to Martin today and is a member of the Privy Council, never lost his enthusiasm for the Chinese commercial market. A multimillionaire--though he is an avowed socialist, his personal motto being, "Think like a socialist, act like a capitalist"--Strong, an honorary director of the Canada China Business Council, has family ties to the Communist state. According to a story told to Elaine Dewar in the Strong biography, Cloak of Green, Strong's cousin was the famous American Marxist writer Anna Louise Strong. After she eventually moved to China, becoming a member of the Comintern, Anna was held in such high esteem by the Maoists that when she died, in 1970, her funeral was personally arranged by former Chinese premier and communist hero Chou En-lai.

Today, Maurice--who some wags have not coincidentally dubbed "Chairman Mo"--also spends much of his time in Beijing, where he keeps an office. That is, when he's not working alongside Secretary General Kofi Annan at the UN, as his special adviser and personal envoy. (In April, Strong stepped aside as the UN special envoy to North Korea after the investigators into the Iraqi oil-for-food scandal revealed he had ties to a Korean accused of bribing UN officials.) He has also been hired as a business consultant to the government of the Chinese province of Anhui. Currently, Strong is working with Anhui to help develop its Chery automobile industry, and has also been hired by former New Brunswick sports car impresario Malcolm Bricklin, who plans to export the Chery to North American markets.

But perhaps Strong's most lasting legacy will be the Kyoto Accord, which is considered to be largely his brainchild, emerging from recommendation from the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, which Strong chaired. And the Chinese should be grateful for it. The accord, while binding the hands of western countries like Canada, by forcing them to lower greenhouse gas emissions, could turn out to be a windfall for the Communists. China, one of the world's worst polluters, thanks to its massive coal burning industries, is not only exempt from achieving any Kyoto targets, it is permitted to sell so-called offset credits, that is, gas allowances it doesn't use, to regulated nations, such as Canada, for millions, perhaps billions of dollars. Canada can also gain greenhouse credits through a process called "joint implementation," whereby Ottawa pays to construct power plants in countries like China that are more efficient than existing infrastructure. In the $10-billion Kyoto plan unveiled in April, the Liberals specified that Canada will both utilize offset credits and joint implementation strategies to meet its Kyoto targets. Meanwhile, companies in China unbound by emissions limits, such as CITIC's electrical generation and manufacturing interests, can only expect to gain more competitive advantage over their North American peers.

While western governments such as Canada's have been taking pains to act as multilaterally as they can, by signing on to agreements such as Kyoto, political observers point out that China plays by a different set of rules. Even if Beijing had sold off all of its carbon emissions credits, it's unlikely it would ever feel obliged to limit its own carbon emissions and risk stifling its thundering economic growth. After all, the Communists routinely flout all sorts of international agreements, from human rights codes to trade rules. "China has proven that despite all the promises it made when it joined the World Trade Organization and everything else, it has no intention whatsoever in being a good international corporate citizen," says the American Foreign Policy Council's Santioli.

If anything, the country that Ottawa seems so eager to do business with is becoming more menacing every year. William Hawkins, senior fellow in National Security Studies at Washington's U.S. Business and Industry Council Education Foundation, visited China last November on a fact-finding tour. He stayed in a CITIC-owned hotel in Zhuhai where the company was promoting a nearby air show, displaying large models of its fighter jets in the lobby. Hawkins remembers the chilling sight of hotel porters dressed like the jet fighter's ground crew and the women behind the front desk decked out like fighter pilots. "So far, Chinese reform has moved from communism to fascism," says Hawkins. "You still have the party running things, but you've just changed the economic system. It's directed capitalism, national capitalism." While the Cold War was fought with the understanding that the Soviet economic system was unworkable, and would eventually collapse on itself, "a China with a booming economy is going to be a much bigger challenge than Communist Russia was," says Hawkins. "China is using its gains from trade to build and finance the next great world power whose ambitions and values are different from ours."

John Thompson, director of the Toronto-based MacKenzie Institute, a security think-tank, says China "scares the hell" out of him--more so, even, than Arab terrorists. "After the jihadists they are the big security threat," says Thompson. "The jihadists are noisy and in our face, but in the long run they are not our real threat. They can be an inconvenience, but if they ever really goad us sufficiently we'll be sorry about what we did to them, but they won't be around. China is the emerging security threat. They are going to give us as severe a challenge as the Nazis and the Fascists in the 1940s."

Washington seems to be taking the signals coming from China--from its huge military buildup to its rocket launches--as that the Communists are jockeying to become the world's second superpower, if not the first, and are warning allies to stop abetting the enemy. In April, the U.S. Department of Defence banned Israel from participating in a massive air force project after Israel agreed to help the Chinese army upgrade its unmanned drones. A few weeks earlier, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice spoke out against a plan by European countries to lift a 15-year ban on arms sales to China, warning that the weapons may one day be used against America. "It is the United States--not Europe--that has defended the Pacific," Rice told a news conference. "The European Union should do nothing to contribute to a circumstance in which Chinese military modernization draws on European technology or even the political decision to suggest that it could draw on European technology."

Rice's comments came just days before she paid a visit to the Red state. While there, she made a point of attending a service at one of the officially atheist nation's few legal churches, as a sign of protest against the Communists' suppression of religious freedoms. It's that kind of public pro-democratic gesture, the sort that Paul Martin scrupulously avoided on his Beijing visit, that optimists like Norm Altenhof hope will pressure the Chinese to reform their fascist state. In the meantime, Martin and those who surround him seem to prefer that things in China stay just the way they are.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!