Screen uncovers hidden ingredients of Chinese medicine

Genetic audit reveals that some traditional remedies contain endangered animals and toxic plants.

Article tools

Rights & Permissions

Chinese herbal medicines contain ingredients derived

from endangered animals, toxic plants and livestock, a genetic audit has

discovered. Few of these ingredients were listed on the packaging.

“There’s absolutely no honesty in the labelling of these products. What they declare is completely at odds with what’s in there,” says Mike Bunce, a geneticist at Murdoch University near Perth, Australia, who led the study. The results are published today in PLoS Genetics1.

Traditional Chinese medicines rack up

billions of dollars in worldwide sales each year, and exports to Western

countries are on the rise. However, most of the medicines have not been

proved to be effective, and industry regulation is scant.

When the medicines have been ground up, it is very difficult to tell what they are made of. In the past, researchers have examined herbal medicines by running assays for toxic compounds and using DNA tests to determine whether a specific plant or animal is present.

But mislabelling is rampant, so researchers do not always know what to look for and conventional approaches will miss many of the species that are present, says Bunce.

His team turned instead to next-generation DNA sequencers, which can rapidly read thousands of DNA strands. The researchers can then check the genetic sequences against databases to learn which plants or animals they come from. This 'deep sequencing' technique has been used to characterize mixtures of microbes living in environments such as oceans and animal guts.

They identified 68 families of plants, including a poisonous herb called Ephedra and the woody vine Aristolochia. Sometimes known as birthwort, Aristolochia contains aristolochic acid, which can cause kidney and liver damage and bladder cancer. Medicinal use of the herb probably explains high rates of bladder cancer in Taiwan, according to a paper published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences2.

At least one of the four medicines that contained Aristolochia DNA also contained aristolochic acid. Other medicines contained DNA from plants in the same family as ginseng — the root of which is illegal to trade internationally — as well as soya and nut-bearing plants, which can cause severe allergic reactions. But many plant DNA sequences could not be pinned to individual species, because plant genetic databases are incomplete.

Nearly half of the medicine samples tested for animal DNA contained genetic material from multiple animals, and more than three-quarters included DNA from animals not listed on the packaging, such as water buffalo, domestic cows and goats.

“Many of those traditional Chinese medicine supplements are such adventurous mixtures of multiple ingredients that, quite frankly, nothing surprises me about them,” says Edzard Ernst, chair in complementary medicine at Peninsula Medical School in Exeter, UK.

Bunce thinks that food and drug regulatory agencies should consider adopting deep-sequencing techniques to screen herbal medicines; his team has applied for a grant to test its methods on supplements that are on the market in Australia. The researchers estimate that in their study, each sample cost US$35, excluding labour, to test, but the cost will fall as DNA sequencing technology becomes cheaper.

“Screening might be a way forward,” says Ernst. “It would be surprising if, among these thousands of ingredients, there were not a few that have the potential to do more good than harm. However, my impression is that we are a very long way from instilling proper science into this area such that patients are not at risk of either direct harm or the indirect harm of treating serious conditions with useless supplements.”

“There’s absolutely no honesty in the labelling of these products. What they declare is completely at odds with what’s in there,” says Mike Bunce, a geneticist at Murdoch University near Perth, Australia, who led the study. The results are published today in PLoS Genetics1.

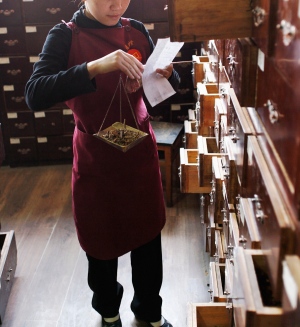

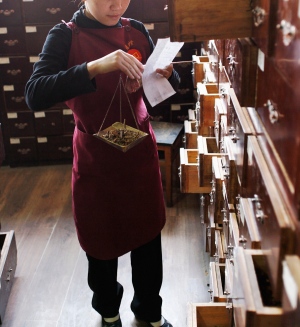

Many traditional Chinese medicines contain species not listed in the ingredients.

Yang Liu/Corbis

When the medicines have been ground up, it is very difficult to tell what they are made of. In the past, researchers have examined herbal medicines by running assays for toxic compounds and using DNA tests to determine whether a specific plant or animal is present.

But mislabelling is rampant, so researchers do not always know what to look for and conventional approaches will miss many of the species that are present, says Bunce.

His team turned instead to next-generation DNA sequencers, which can rapidly read thousands of DNA strands. The researchers can then check the genetic sequences against databases to learn which plants or animals they come from. This 'deep sequencing' technique has been used to characterize mixtures of microbes living in environments such as oceans and animal guts.

More harm than good

Bunce’s team sequenced DNA from 15 traditional Chinese medicine preparations that had been seized by Australian customs, including powders, tablets and teas. Focusing on DNA from chloroplasts and mitochondria — energy-producing structures in cells that have their own genomes — the researchers produced 49,000 genetic sequences.They identified 68 families of plants, including a poisonous herb called Ephedra and the woody vine Aristolochia. Sometimes known as birthwort, Aristolochia contains aristolochic acid, which can cause kidney and liver damage and bladder cancer. Medicinal use of the herb probably explains high rates of bladder cancer in Taiwan, according to a paper published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences2.

At least one of the four medicines that contained Aristolochia DNA also contained aristolochic acid. Other medicines contained DNA from plants in the same family as ginseng — the root of which is illegal to trade internationally — as well as soya and nut-bearing plants, which can cause severe allergic reactions. But many plant DNA sequences could not be pinned to individual species, because plant genetic databases are incomplete.

Mix and match

The researchers also found DNA from eight genera of vertebrate animals. Genetic material from the critically endangered Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica) was present in one powder; and boxes marked as bear-bile powder or decorated with the outline of a bear contained traces of DNA from the Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus), which is classed as vulnerable.Nearly half of the medicine samples tested for animal DNA contained genetic material from multiple animals, and more than three-quarters included DNA from animals not listed on the packaging, such as water buffalo, domestic cows and goats.

“Many of those traditional Chinese medicine supplements are such adventurous mixtures of multiple ingredients that, quite frankly, nothing surprises me about them,” says Edzard Ernst, chair in complementary medicine at Peninsula Medical School in Exeter, UK.

Bunce thinks that food and drug regulatory agencies should consider adopting deep-sequencing techniques to screen herbal medicines; his team has applied for a grant to test its methods on supplements that are on the market in Australia. The researchers estimate that in their study, each sample cost US$35, excluding labour, to test, but the cost will fall as DNA sequencing technology becomes cheaper.

“Screening might be a way forward,” says Ernst. “It would be surprising if, among these thousands of ingredients, there were not a few that have the potential to do more good than harm. However, my impression is that we are a very long way from instilling proper science into this area such that patients are not at risk of either direct harm or the indirect harm of treating serious conditions with useless supplements.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!