Chinese-Built Zambian Smelter Stirs Controversy

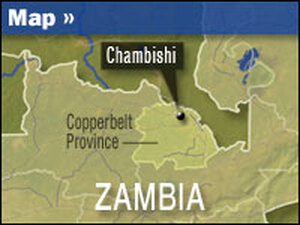

China is hungry for Zambia's copper and has become increasingly active in Zambia's Copperbelt Province, once a preserve of colonial Britain.

While the Zambian government is upbeat about Chinese investments and involvement, there has been anti-Chinese unrest and rioting among Zambian copper workers over low pay and poor working conditions.

Officials in Zambia talk proudly and confidently about the southern African nation's relationship with China. The countries' courtship began in the independence era, when apartheid had taken hold in nearby South Africa.

Zambia played a pivotal role helping South Africa's black majority fight the liberation struggle against white minority rule. So the apartheid government cut off routes to South Africa's seaports from landlocked, copper-exporting Zambia. And that, says Finance Minister Ng'andu Peter Magande, is when China stepped in.

Investing At A Dizzying Pace

"China was the only country that helped us in the '60s to build the Tazara Railway, some 3,000 kilometers of railway line," Magande says. "So to us, what is happening now is China is continuing to come and looking at new sectors — like in the mining sector, in agriculture. So really for us, it's nothing new."

But the scale and breadth of China's recent interests and investments in Zambia are new, and they're moving at a truly dizzying pace. Magande says China is an attractive partner.

"Currently, we believe that this is extremely important," he says. "We see a lot of Chinese investors coming to Zambia, so I'd say that in the 20th century, Europe was interested and the West did exploit our raw materials. But this time in the 21st century, we have found new investors that are coming back to try to help us to move ahead."

Opposing Chinese Influence

But not all Zambians are pleased about China's enhanced role in Zambia. And some have expressed deep unease about recolonization in Africa.

Michael Sata, nicknamed King Cobra, is Zambia's feisty opposition leader. He failed in a bid to become president two years ago, campaigning on an anti-China platform. Sata speaks of exploitation.

"Today, the Chinese are not here as investors, they are here as invaders," Sata says.

"They bring Chinese to come and push wheelbarrows, they bring Chinese bricklayers, they bring Chinese carpenters, Chinese plumbers — we have plenty of those in Zambia. Pushing a wheelbarrow is pushing a wheelbarrow. They're doing manual work. We don't need to import laborers from China — we need to import people with skill, with skills which we don't have in Zambia. But the Chinese are not going to train our people how to push wheelbarrows."

There are plenty more complaints from Zambians about the new bosses and Chinese-run industries, especially in what was the rundown copper sector.

But there is praise, too. In the Copperbelt Province, multimillion-dollar Chinese investment is highly visible. In the early morning haze, copper workers head off to the mines and to the giant copper smelter the Chinese have almost finished building in Chambishi.

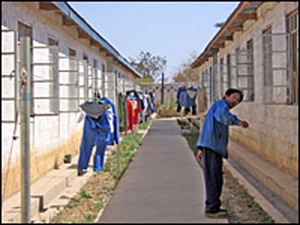

The Chambishi Copper Smelter compound is no-frills, dominated by the huge, electric-blue smelter in the final stages of construction. Three flags flutter in the wind: Zambia's, China's and the Chinese company's. There are rows of dormitories for Chinese technicians, with the wash hanging out to dry. There is a dining hall in front and a large echoing boardroom.

'A Win-Win Project'

Zi Xuting, assistant CEO for Chambishi Copper Smelter Ltd., is originally from Yunnan Province in southwest China but has lived in Zambia for the past two years. He says the mighty copper smelter is due to come into commission by the end of the year — and that all sides are benefiting from the deal.

"For the Zambians, what they got is tax, employment opportunities and industry development. For China, they got the copper. Chinese and Zambians are brothers," Zi says, laughing. "It's a win-win project."

Although Zi is welcoming, speaking with any of the Chinese or Zambian workers — almost all men — who came streaming out of the smelter construction site on lunch break in a sea of blue and yellow hard hats is prohibited.

This may be because back in March, 500 Zambian employees were suspended after rioting over low wages and unsafe working conditions. They allegedly attacked a Chinese manager at the smelter, and about 50 workers were fired.

George Jambwa, a Zambian journalist turned public relations executive, was the spokesman at Chambishi at the time of the unrest.

"It was tense," Jambwa says. "It was well-planned by the workers themselves. The Zambians started throwing stones, and the workers started damaging property. That's when the Chinese workers came out with all sorts of weapons to come and protect the other property. So that's when there was commotion. The police were called in — it was a very difficult situation."

Magande says cultural differences and expectations should not preclude a work regime and ethic that all sides can accept.

"The Chinese were very frank with us," Magande says. "They told us, 'When we come to your countries, tell us your procedures, tell us your traditions, tell us your systems. Then we can sit down and tell you our systems and, together, we find a brand of what is going to win.'"

Such talk enrages Sata. A Chinese-run copper mine explosion killed about 50 Zambian workers three years ago, which he says is proof of dangerous working conditions. He adds that dubious Chinese labor practices were widespread in Africa.

"It is not only Zambia — it's all Cape to Cairo where the Chinaman is," Sata says. "That's the way they look at us. They have no regard for us. They have no regard for our independence. They have no regard for any black person as a human being. Those are very abnormal conditions, very abnormal conditions. Very abnormal conditions, which a civilized society, in this century, cannot accept."

But not all Zambians are opposed to the Chinese. In Chambishi Township market, there is considerable support.

Bernadette Malama, a teacher there, says it's good that the Chinese have come to the area. Along with employment and a reduction in crime, they contribute to the economy by buying market items such as peanuts, oranges and potatoes.

"These people, I would only say that they are just almost like us," Malama says of the Chinese. "We use sign language and sometime broken English. We are going to live with them for a longer time. We are going to learn their language."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!