|

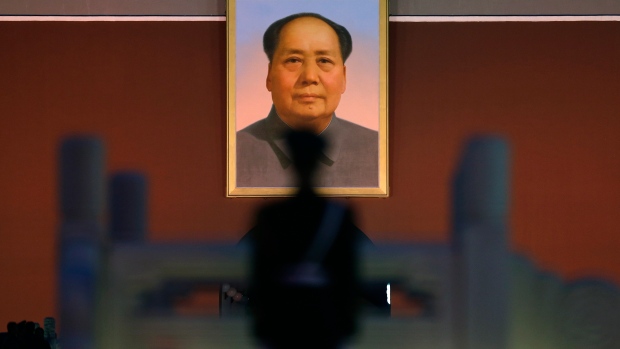

A security guard mans his post in front of the CNOOC global headquarters

in Beijing, 23 October 2007.

(Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images) |

The proposed

$15.1billion takeover of Calgary-based

Nexen, Canada’s sixth largest oil company, by government-owned

China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) is one of Beijing’s largest foreign buyout attempts to date.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China are unlike responsible publicly traded and private businesses in Canada, instead

operating as extensions of the party state, often with priorities far different from the concerns of customers, employees and shareholders.

Stephen Harper’s Conservative government must decide whether or not to approve the purchase under the vague “net benefit” and “national security” tests in the

Investment Canada Act. It is important to keep in mind that what is sought is a complete change of ownership of a business with about 3,000 employees, which has been operating in a socially responsible manner in Canada and internationally for many years.

The takeover would constitute

Nexen’s nationalization by the party state in Beijing.

CNOOC is controlled by its parent,

China National Offshore Oil,

wholly owned by the Chinese government, which is in turn dominated from top to bottom by the

Communist Party. A similar offer was made by CNOOC for

Unocal of California in

2005, but was halted in the face of opposition in

Congress and by American public opinion.

China Minmetals considered a takeover the same year of

Noranda, then Canada’s largest mining enterprise, but abandoned it when Canadians became aware that Minmetals was a branch of the mines department of the government of China.

The board chair of CNOOC,

Wang Yilin, is also the

secretary of the party branch in the business.

Charles Burton, the academic and former Canadian cultural attaché in Beijing, explains:

“CNOOC’s party committee has a party discipline inspection group whose head, Zhang Jianwei, is also a senior member of the CNOOC board. Zhang’s job is to make sure that all the leaders of Nexen comply with the secret directives of the party leadership in Beijing … it is difficult to believe this will all go the way CNOOC, its Canadian lawyers, PR agencies and ‘pro-China’ Canadian supporters say it will…

The Economist magazine concluded in its Jan. 21 edition about China’s model of state capitalism:

“The Chinese party-state is the largest shareholder in the country’s 150 largest companies and directs thousands of others… A culture of corruption permeates China’s economy today, with Transparency International ranking it far down its list at 75th place on its perceived corruption index for 2011.”

The magazine quotes a central bank of China estimate that, between the mid-1990s and 2008, up to 18,000 Chinese officials and executives of state-owned companies “made off with a total of $123 billion” (averaging about $6 million each) and concluded, “by turning companies into organs of the government,

state capitalism simultaneously concentrates power and corrupts it.”

The Party, published in 2010 by

Richard McGregor, former China bureau chief for the

Financial Times, documents its continuing grip on the government, courts, media and military.

“Top leaders adhere to Marxism in their public statements, even as they depend on a ruthless private sector to create jobs … (It) has eradicated or emasculated political rivals; eliminated the autonomy of the courts and press; restricted religion and civil society; denigrated rival versions of nationhood; centralized political power; established extensive networks of security police; and dispatched dissidents to labour camps.”

Consider the conduct of Chinese SOEs globally. When the

China National Petroleum Corp. took a stake in

Sudan’s oil fields in 1996, Beijing subsequently backed the

al-Bashir regime in Khartoum, selling it arms and providing diplomatic cover at the

UN Security Council.

Bashir and his agents committed systematic atrocities in south Sudan and Darfur for which he has been indicted by the International Criminal Court. Africans also accuse Chinese resource companies of underbidding local firms and not hiring local residents. In

Zambia, Chinese mining companies

banned union activity, and in two instances, were

charged with attempted murder after opening fire on local employees protesting work conditions. Its SOE roles in Iran and elsewhere are similarly controversial.

In Canada, the SOE

Sinopec flew 150 Chinese workers into Alberta in 2007 to build a storage tank on an oil project.

Two were killed and two were injured when the tank roof collapsed. When the Alberta government laid charges for failing to protect its workers, Sinopec’s construction company

denied a presence in Canada (no doubt recognizing that this position might affect the bid for Nexen, the company recently pleaded guilty).

Major corporations are above the law in China and routinely ignore safety, environmental and employment legislation with impunity.

On Oct. 17,

Lucy Zhou of the Falun Dafa Association of Canada said the association has now identified

76 people persecuted by CNOOC and its subsidiaries for practicing Falun Gong. CNOOC fired employees that practiced Falun Gong or cut their wages. It imprisoned employees and used company security personnel to force them into detention and brainwashing facilities.

In short, Chinese SOEs in general and CNOOC in particular, being dominated by the political views of the Communist Party,

violate values held dearly by Canadians, including the right to dignity, safe working conditions, to bargain collectively, and the right not to be persecuted for religious reasons. The revelations in recent days that CNOOC has persecuted its Falun Gong employees should be the final straw in deciding that the proposed buy-out is

not in Canada’s interest.

Beijing would not for a moment permit a foreign government or private company to take over a major business like Nexen in China.

There is no reciprocity between China and Canada in trade and investment; the bilateral investor protection agreement, which took 18 years to negotiate, is now signed in some form, but not yet ratified by both sides.

The courts and entire legal system in China, moreover, are controlled and administered by the party. Judgments in disputes between Chinese and foreign parties are

politically, rather than judicially, driven; there is seldom a political reason to uphold a claim by a foreign entity against a Chinese one.

Canadians have indicated decisively through opinion surveys and other avenues the extent of opposition across the country to the proposed Nexen takeover. In a recent

Angus Reid poll

58 percent of those interviewed want Ottawa to reject the CNOOC takeover of Nexen (vs. 12 percent urging the government to give it the green light). Not surprisingly,

opposition to the deal was strongest in British Columbia (69 percent) and Alberta (63 percent) where more people are directly exposed to the Chinese invasion of the Canadian natural resource ‘patch’ and, rather remarkably, quite universal across the political spectrum:

57 percent of Conservatives were in the Naye category, as were

65 percent of NDPers and

69 percent of Liberals.

And when asked if they thought foreign governments should be allowed to gain control over natural resources on Canadian soil, the Nayes soared to

78 percent.

In blocking the Nexen takeover, the Harper government should publish a set of regulations for SOEs, whether they are publicly traded or not, to govern all foreign takeovers. Any SOE, regardless of national origin, will be limited to a

minority shareholding in any Canadian business. CNOOC might be told that it can own up to 20 per cent of Nexen, provided that no other entity linked to the party state in China attempts in future to purchase any additional ownership.

David Kilgour is a former Canadian Secretary of State (Asia-Pacific) and MP for southeast Edmonton.

Clive Ansley is a Canadian human rights lawyer and former professor of Chinese law, who practiced in China for 14 years.