Thousands of Hong Kong-born people move back to Canada, once again reversing a migration that has shaped cities across the Pacific

- Canada’s Hong Kong-born population has increased for the first time since 1996, upending a flow that resulted in 300,000 Canadians living in the autonomous city

- Academics say political upheaval, personal factors and the ageing of Canadians in Hong Kong are behind the new phenomenon of double-reverse migration

Thousands of Hong Kong people are returning to Canada, as so-called reverse migrants change direction once again, according to census data uncovered by the South China Morning Post.

The figures show that the population of Hong Kong-born people in Canada has increased for the first time since 1996 – thanks to the new phenomenon of double-reverse migration, or re-returneeship.

A massive process of reverse migration, by people who headed back to Hong Kong after obtaining Canadian citizenship, had resulted in an estimated 300,000 Canadians living in the city and reshaped cities across the Pacific, including Vancouver and nearby Richmond in British Columbia.

But the Canadian census data now shows that the flow has changed direction, with at least 8,000 double-reverse migrants and their children moving to Canada from Hong Kong in the five years before Canada’s last census, in 2016.

Friends Natalie Tam, 17 (left), and Chinnie Liu, 16, are both children of reverse migrants. Born in Hong Kong, they both moved to Vancouver last year. Photo: Ian Young

University of British Columbia geographer Professor Daniel Hiebert, who studies migration, said the Post’s findings “make perfect sense – at least in theory”.

“Let’s say a Hong Kong person first immigrated to Canada in the big wave, at about [age] 40 or 45 in 1990. Life in Canada is nice but somewhat boring and opportunities are limited,” he said.

“So, back to Hong Kong. But now that person is 65 or 70 and maybe doesn’t care so much about living in a bustling city and retires. Where to live? Maybe Canada begins to look quite good.”

They leave Hong Kong not just because they are against China or they don’t like the Communist Party, but because they don’t want the political struggle practically impacting their daily life

Kennedy Chi-pan Wong, a University of British Columbia graduate who is researching re-returnees, said a combination of political and personal reasons were behind the process.

Hong Kong’s political struggles were “like the ghost haunting them”, said Wong of the re-returnees he interviewed for his unpublished research.

“It is something impacting their emotions, the way they interact with others, especially since the umbrella movement [the 2014 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong] … They think moving to another place is the better option,” he said.

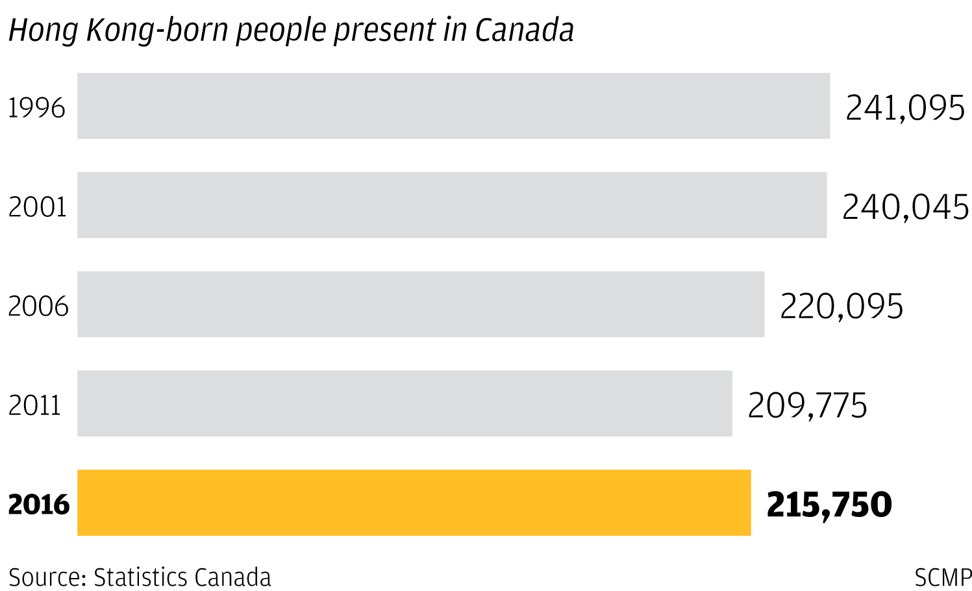

The number of Hong Kong-born people present in Canada increased by 5,975 between 2011 and the 2016 Census, from 209,775 to 215,750.

That exceeds the 4,970 new Hong Kong immigrants arriving in Canada for the first time in that period, and therefore shows that the presence of previous Hong Kong immigrants or their children returning to Canada also rose.

But the rising number of Hong Kong-born people must also overcome the Canadian death rate of about

. This represents about 7,750 expected deaths of Hongkongers from 2011 to 2016 – suggesting a net estimate of 8,755 reverse migrants or their children headed back to Canada in that period.

. This represents about 7,750 expected deaths of Hongkongers from 2011 to 2016 – suggesting a net estimate of 8,755 reverse migrants or their children headed back to Canada in that period.

The true number is almost certainly higher than 8,755 for two reasons: one, the age of Hong Kong-born people in Canada already skews higher than that of the general population, suggesting a higher death rate; and two, the net inflow must first match any continued outflow of single-reverse migrants.

The data cannot show exactly when the flow reversed in the five-year period.

By comparison, the number of Hong Kong people in Canada fell by 10,320 from 2006 to 2011.

Jenny Liu, seen in Hong Kong, is now a double-reverse migrant, having moved to Canada as a teenager in the early 1990s, back to Hong Kong in 1998, then back to Canada in 2015.

Taking into account expected deaths of about 8,130, and the inflow of 4,805 new immigrants, that works out to a net outflow from Canada of about 6,995 reverse immigrants in that period.

The number of Hong Kong immigrants present in Canada had been falling since the 1996 census, when they numbered 241,095. After a modest decline of about 1,000 in the next five years, they fell sharply over the next decade.

Among the double-reverse migrants is Jenny Liu, who works in human resources in Vancouver. She originally moved there as a teenager with her family in the early 1990s.

After finishing high school and getting a business degree at the University of Windsor, Ontario, she returned to Hong Kong in 1998. She and her parents moved back to Vancouver in 2015.

Now in her 40s and married, Liu has no plans to return to Hong Kong. “Hong Kong has changed a lot,” she said, adding she felt sad for relatives without foreign passports who had no option to leave.

The “leading factor” for her return to Canada was the selection of Leung Chun-ying as Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2012; he was reviled by many liberals in the city.

“At that moment, I planned to move back [to Canada] within two or three years,” she said.

Although the political situation in Hong Kong would deter her from returning, the massive anti-extradition protest on the weekend had made her feel more like a Hong Kong person, she said.

She stayed up until midnight following the protests online, then got up at 5am on Sunday to check the situation again.

“I couldn’t go to sleep, I was so worried about them [the protesters],” Liu said. On Sunday, she attended a protest outside the Chinese consulate-general in Vancouver, in solidarity with the protesters in Hong Kong.

Also at the Vancouver protest on Sunday were friends Natalie Tam, 17, and Chinnie Liu, 16.

Both moved to Vancouver last year, having been born as Canadians in Hong Kong, the children of reverse immigrants whose parents had returned to Hong Kong in 1997 and 1989, respectively.

Liu’s parents have since become double-reverse immigrants who returned to Vancouver with her, while Tam’s parents remain in Hong Kong.

Despite being happy in Canada, Liu’s connection to the autonomous city remained strong. “Hong Kong is my home. I love it,” she said, explaining her presence at the protest.

Protesters against the Hong Kong-China extradition law are reflected in the nameplate of the Chinese consulate general on Granville St, Vancouver, on Sunday. Photo: Ian Young

Wong, the researcher, said the complex processes of reverse and double-reverse migration raised a host of questions about their participants.

“How do they form their identity? How do they form a sense of home?” said Wong, who hosted a forum on re-returnees in Richmond, outside Vancouver, on Sunday.

He said his research had found “political reasons-plus” were motivating the migrants.

Some wanted better educational opportunities for their children, but this was a crossover factor; some feared their children’s schooling would be undermined by political considerations such as the so-called “national education” curriculum in Hong Kong schools, which was withdrawn after mass demonstrations in 2012.

“This was a practical political concern, not so much an ideological political concern,” Wong said.

“They leave Hong Kong not just because they are against China or they don’t like the Communist Party, but because they don’t want the political struggle practically impacting their daily life.”

Professor Hiebert said he suspected the ageing of reverse immigrants in Hong Kong was mainly at play.

“I suppose there may also be some element related to the political situation of Hong Kong, but I’d start with the demographics,” he said.

University of British Columbia geographer Daniel Hiebert. Photo: Peter Wall Institute/UBC

The estimated 300,000 Canadian citizens in Hong Kong far exceeds the net losses of Hong Kong-born people from Canada that occurred after the handover.

This is because their number includes many who returned to Hong Kong well before the handover, like Liu’s parents, as well as the children of reverse immigrants, and expatriate Canadians.

The net losses from Canada also take into account the inflow of new immigrants.

The Post’s findings on double-reverse migration correspond with recent data on new immigration from Hong Kong to Canada, which showed a significant spike in 2016, when 1,210 Hongkongers became permanent residents of Canada, in the wake of political unrest in the city.

More than 300,000 Hongkongers migrated to Canada in the 1980s and 1990s, hitting an annual peak of 44,271 in 1994. But in 1998, after the handover, immigration plummeted.

From 2000-2012, new Hong Kong immigrants to Canada averaged only 471 per year.

The population of mainland Chinese-born people in Canada, however, has been soaring by about one third every five-year census period.

Their presence overtook that of Hong Kong-born people around the time of the 1997 handover, rising from 231,055 at the 1996 census to 752,650 at the 2016 census.

As reverse migration drained Hongkongers from places like Richmond and Vancouver in British Columbia, they were swiftly supplanted by booming numbers of mainland Chinese immigrants.

Reflecting this shift, Mandarin is now on the brink of replacing Cantonese as the most-spoken non-English mother tongue in both cities.

Mainland Chinese immigrants are the most prevalent foreign-born people in Canada, ahead of people from India (728,160), the Philippines (626,090) and Britain (528,245).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!