U.S.-CHINA

ECONOMIC and SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION

FENTANYL FLOWS FROM CHINA: AN UPDATE SINCE 2017

November 26, 2018

Fentanyl Flows from China: An Update since 2017

Sean O’Connor, Policy Analyst, Economics and Trade Acknowledgments: The author thanks Jeffrey James Higgins and officials at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration for their helpful insights. Their assistance does not imply any endorsement of this report’s contents, and any errors should be attributed solely to the author. Key Findings

China remains the largest source of illicit fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances in the United States: Since the publication of the Commission’s 2017 staff report on fentanyl flows from China, there has been no substantive curtailment of fentanyl flows from China to the United States. In large part, these flows persist due to weak regulations governing pharmaceutical and chemical production in China.

U.S. and Chinese government negotiations for increased counter-narcotic cooperation are ongoing: Chinese officials have shown a willingness to work with their U.S. counterparts, controlling 39 new substances

since February 2017 and assisting with U.S. law enforcement investigations into alleged Chinese drug traffickers.

Beijing’s scheduling procedures remain slow and ineffective: Because the Chinese government schedules chemicals one by one, illicit manufacturers create new substances faster than they can be controlled. U.S. officials have proposed strategies for Beijing to systematically control all fentanyl substances, but the changes have not been approved by the Chinese government.

U.S. law enforcement agencies are taking legal actions against known Chinese drug traffickers: Efforts to sanction or indict known Chinese drug traffickers represent a new approach to create greater pressure on Chinese counternarcotic officials. Overview of Chinese Fentanyl and Other Illicit Synthetic Opioid Flows to the United States In February 2017, the Commission published a staff report titled Fentanyl: China’s Deadly Export to the United States, which detailed how illicit flows of fentanyl and other new psychoactive substances (NPS) from China are fueling an opioid crisis in the United States.* The 2017 report’s conclusions remain accurate, including that:

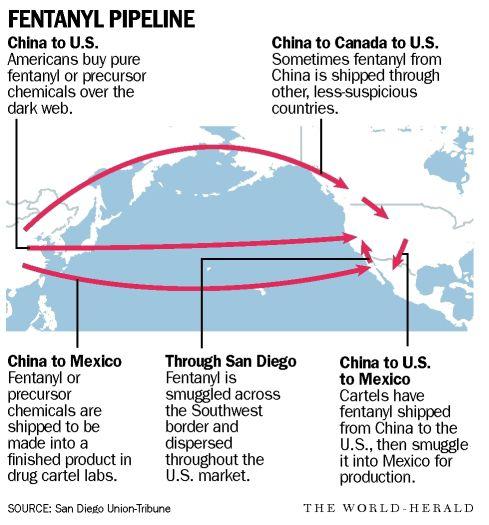

China remains the largest source of illicit fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances in the United States. Fentanyl, a synthetically produced opioid, is shipped from China either directly to the United States or to * For more on fentanyl flows from China to the United States, see Sean O’Connor, “Fentanyl: China’s Deadly Export to the United States,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, February 1, 2017.

https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/USCC%20Staff%20Report_FentanylChina%E2%80%99s%20Deadly%20Export%20to%20the%20United%20States020117.pdf. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission 2 Mexico (and to a lesser extent Canada) before it is trafficked over the U.S. border (see Figure 1). Domestically, China does not have a fentanyl abuse problem. 1

China is a global source of fentanyl-like substances and other NPS because the country’s vast chemical and pharmaceutical industries are weakly regulated and poorly monitored, allowing producers to manufacture and export dangerous substances (both controlled and uncontrolled) without detection.

2 China’s inefficient chemical and pharmaceutical regulatory environment is due in part to misaligned incentive structures for local governments, which are encouraged to prioritize economic growth and development objectives above all else. It is also due to the fragmented nature of China’s administrative system that oversees the production and export of chemical and pharmaceutical products.3 ;

The chemical structures of fentanyl analogues and other NPS can be modified in an endless number of combinations to create chemically similar yet distinct substances.4 Because the Chinese government—like other governments around the world—schedules chemicals one by one, Chinese manufacturers stay ahead of regulators by creating new, uncontrolled substances that can be legally manufactured and exported.5

Chinese chemical exporters covertly ship drugs to the Western hemisphere by using a chain of forwarding systems, mislabeling narcotic shipments, and modifying chemicals so they are not subject to controls, among other methods. Chinese distributors also use online marketplaces to mask their identities while reaching potential customers in the United States and around the world.6 Figure 1: Illicit Synthetic Opioid Flows from China Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office, Illicit Opioids: While Greater Attention Given to Combating Synthetic Opioids, Agencies Need to Better Assess Their Efforts, March 2018, 10. https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/690972.pdf. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission 3 Status of U.S.-China Counter-narcotic Negotiations Key updates since February 2017: Negotiations remain ongoing, with limited visible progress outside of recent scheduling actions by Beijing. U.S. counter-narcotic officials have proposed new strategies for Beijing to systematically control new NPS, but the Chinese government continues to schedule new substances one by one. U.S. and Chinese government officials continue to enhance bilateral cooperation for combating illicit drug and chemical flows, including increased intelligence and information sharing.7 In testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee in September 2018, Paul E. Knierim, the deputy chief of operations at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Office of Global Enforcement, indicated these efforts have yielded positive actions taken by the Chinese government, but that more can be done to increase U.S.-China counter-narcotic cooperation. According to Mr. Knierim, the DEA maintains a “very robust dialogue and engagement” with its counterparts in China, including information exchanges that help U.S. law enforcement seize dangerous substances and identify traffickers.8 However, progress securing Chinese government commitments to control new chemicals—namely fentanyl analogues and precursors—remains slow and ineffective. The Chinese government controls new chemicals one by one, reviewing each substance individually (often with input from the DEA) to decide whether it has legitimate medical or pharmaceutical uses, and, if not, whether it is addictive, harmful, or has the potential to be abused. * This method’s effectiveness is limited when dealing with synthetic drugs, as manufacturers modify the chemical structure of NPS once they are controlled to create “new” chemical analogues that are technically legal and permissible to export. † 9 Daniel D. Baldwin, the section chief of the DEA’s Office of Global Enforcement, testified to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations that China’s Narcotic Control Bureau recognizes its scheduling process is “long and complicated,” but has not taken significant steps to streamline these processes.10 The same problem exists for U.S. law enforcement officials; under current U.S. scheduling laws (codified in the Controlled Substances Act), each substance is scheduled individually, making it difficult to keep pace with producers creating new substances to evade international chemical controls.11 The DEA can temporarily schedule substances not listed in the Controlled Substances Act for up to two years if they are deemed present an imminent threat to public safety.12 U.S. negotiators have proposed several strategies to their Chinese counterparts for creating more effective scheduling processes. According to DEA officials who spoke with Commission staff, the most recent of these strategies was to urge Beijing to consider a new regulation establishing fentanyl as its own class of controlled substances, allowing all known and future fentanyl analogues to be automatically controlled in China. According to the DEA officials, Beijing was receptive to the idea.13 However, similar suggestions have failed to gain approval from Chinese regulators in the past. In 2016, U.S. negotiators believed they had secured an agreement with Chinese regulators that China would commit to targeting U.S.-bound exports of substances controlled in the United States, but not in China. 14 Under such an agreement, all substances controlled by U.S. regulators would automatically be illegal in China for the purposes of export to the United States, even if the substance was not controlled in China. A Chinese readout from the same discussion, however, did not include making the commitment, and Beijing never implemented the policy. 15 * Chinese chemical controls require that the substance has no known medical use. The Chinese government then considers the following factors to decide whether the substance should be controlled: addiction or potential to be addictive; danger posed to humans’ physical and mental health; whether the substance is being illicitly manufactured, transported, or smuggled; and the current abuse situation and potential for increased abuse (either domestically or internationally). Official, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, interview with Commission staff, September 18, 2018. † Worldwide, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimates one new NPS is created every week. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Global Synthetic Drugs Assessment,” 2017, 21. https://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/Global_Drugs_Assessment_2017.pdf. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission 4 Chinese NPS Regulatory Environment Key updates since February 2017: The Chinese government has placed controls on 39 additional NPS and has announced reforms to several agencies responsible for regulating chemical production and export. Since 2017, the Chinese government has taken steps to streamline regulatory oversight of NPS production and export and to expand the number of controlled substances in China, yet it remains unable or unwilling to fully crack down on illicit NPS producers operating throughout the country.16 The Chinese government has publicly indicated a willingness to cooperate with U.S. counter-narcotic efforts, with Liu Yuijin, the deputy head of China’s National Narcotics Commission, saying in June 2018 that “China’s drug control agencies, now and in the years to come, will place greater emphasis on drug control cooperation between China and the United States.” 17 However, Jeffrey Higgins, a former supervisory special agent at the DEA, told Commission staff that he felt China is merely seeking to create the appearance of cooperating with U.S. officials, while not enacting any reforms to its chemical and pharmaceutical industries that may slow the country’s economic growth.18 China has implemented several new chemical controls since February 2017, including controlling some known fentanyl analogues. The Chinese Ministry of Public Security has announced controls on 170 NPS, including 25 fentanyl substances.19 Chinese scheduling actions since February 2017 include: (1) in March 2017, China placed controls on four fentanyl-class substances: carfentanil, furanyl fentanyl, valeryl fentanyl, and acryl fentanyl;20 (2) in July 2017, China controlled U-47700, a powerful synthetic opioid (though not a fentanyl-class substance);21 (3) in February 2018, China placed scheduling controls on two popular fentanyl precursor chemicals, NPP and 4ANPP;22 and (4) in August 2018, China controlled an additional 32 NPS, including two fentanyl substances.23 However, these scheduling actions have little long-term impact on reducing NPS flows to the United States.24 Manufacturers modify chemicals to create new substances faster than old ones are able to be controlled. In a June 2017 interview with the Globe and Mail, Yu Haibin, a division director at the Chinese Ministry of Public Security’s Narcotics Control Bureau, conceded that Chinese regulators are struggling to keep pace with illicit NPS producers, saying, “My feeling is that it’s just like a race and I will never catch up with the criminals.”25 China has announced reforms to agencies tasked with regulating chemical production, but it remains unclear how these changes will be implemented or to what degree they will improve China’s regulatory environment. In 2017, China updated its chemical industry regulations to, among other things, require chemical companies to notify the government before creating new chemical substances and acquire explicit approval from the government for exports and imports of toxic chemicals. 26 In March 2018, China’s National People’s Congress announced it would restructure the roles of the major regulatory bodies responsible for overseeing the chemical industry, including the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the State Administration of Work Safety, and the China Food and Drug Administration. These reforms, which went into effect in July 2018, are primarily intended to strengthen environmental management but may impact oversight of China’s chemical industry.27 The Chinese government has indicated these reforms will improve regulatory efficiency and oversight. 28 However, some chemical industry observers believe the changes will not affect China’s management of chemical production and export, while other analysts fear the changes could create uncertainty among agencies about where the jurisdiction and responsibilities lie vis-à-vis regulating chemical products. 29 Others worry the organizational changes may lead to an unwinding of previously announced policies, including the 2017 updates to chemical industry regulations, leading to more lenient policies for chemical producers. For example, Lisa Zhong, a product registration and compliance project manager at the state-owned China National Chemical Information Center, indicated she is “not sure whether the progress of the [2017] regulation update will be affected” by these organizational reforms.30 U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission 5 U.S. Efforts to Stem Illicit NPS Flows from China Key updates since February 2017: The U.S. Congress is considering several pieces of legislation to crack down on illicit NPS flows from China, and the U.S. Departments of Justice and the Treasury have taken legal action against several prominent Chinese NPS traffickers. Legislation Congress is considering several bills to enhance law enforcement’s ability to identify, control, and seize dangerous NPS, including those coming from China. Three notable pieces of legislation recently signed into law or under consideration include: 1. The Synthetics Trafficking and Overdose Prevention (STOP) Act of 2018: This legislation, signed into law in October 2018, directs the U.S. Postal Service to “require the provision of advance electronic information on international mail shipments.”31 Prior to implementation of the STOP Act, the U.S. Postal Service was not required to provide advanced electronic data on packages, unlike private companies such as UPS or FedEx, which provide advanced electronic data that can help law enforcement identify and seize illicit substances sent over the mail.32 2. The Stop the Importation and Trafficking of Synthetic Analogues (SITSA) Act of 2017: This legislation would amend the Controlled Substances Act to allow synthetic drug analogues to be immediately scheduled on a temporary basis while drug enforcement agencies investigate the risk the substance could pose.33 3. The Stopping Overdoses of Fentanyl Analogues (SOFA) Act: This legislation would amend the Controlled Substances Act to classify certain fentanyl analogues as Schedule I controlled substances, and ensure any derivatives of those analogues are automatically controlled. 34 In February 2018, the DEA issued a temporary order to schedule fentanyl-related substances not currently listed under the Controlled Substances Act as Schedule I substances effective through February 2020.35 Law Enforcement Actions U.S. law enforcement agencies have begun indicting Chinese nationals trafficking illicit NPS in the United States, relying in part on intelligence provided by the Chinese government. In September 2017, federal prosecutors in Mississippi and North Dakota charged two Chinese nationals for “conspiracies to distribute large quantities of fentanyl and fentanyl analogues and other opiate substances in the United States.” 36 This marked the first time Chinese nationals had been indicted for fentanyl trafficking in the United States.37 In August 2018, two additional Chinese nationals were indicted by a federal court in Ohio for manufacturing and shipping fentanyl analogues and 250 other drugs to at least 25 countries and 37 U.S. states.38 The Chinese Ministry of Public Security provided assistance for both the September 2017 and August 2018 investigations. 39 In April 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated five Chinese fentanyl traffickers for sanctions under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, the first time the law had been used to target an alleged fentanyl trafficker. 40 Jian Zhang was identified as the head of the trafficking network after he was found to be using his China-based chemical company (which was registered in Hong Kong) to facilitate the import of fentanyl and other NPS into the United States. 41 The other four Chinese nationals designated for sanctions were financial associates of Mr. Zhang who laundered the illicit narcotics proceeds for Zhang’s company. * The Department of Justice also * As a result of the sanctions, the five individuals’ U.S. assets—including their property and interests in the United States or in possession of a U.S. citizen—are blocked and must be reported to Treasury. U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury Sanctions Chinese Fentanyl Trafficker Jian Zhang, April 27, 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0372. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission 6 announced indictments against the five individuals. * In a press release about the decision, Sigal Mandelker, undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence at Treasury, said the decision to impose sanctions “will disrupt the flow of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids into the United States, and serves as a warning that Treasury will continue to target the assets of those who deal in illicit opioids and synthetic narcotics.” 42 A Way Forward for U.S. Negotiators: The Case of Flakka The use of law enforcement tools against Chinese fentanyl traffickers represents a new means of exacting pressure on Chinese counternarcotic officials. A similar strategy was used in 2015, when an outbreak of overdoses linked to an NPS known as flakka† occurred in Florida. Flakka, like fentanyl, was being made in China and sent to the United States, contributing to 63 deaths in South Florida between September 2014 and December 2015. 43 In October 2015, after U.S. law enforcement identified one Chinese national as the head of the flakka trafficking network in China, Treasury imposed sanctions on him and his chemical company.44 The next month, Florida law enforcement officials and local DEA agents visited China as part of an ongoing campaign to pressure the Chinese government to place controls on flakka.45 Shortly after the visit, China announced it had added flakka, along with 115 other NPS, to its list of controlled substances.46 Just months later, flakka all but disappeared from Florida, with no flakka-related deaths in the United States in 2016.47 The current opioid crisis will not be as easily solved as the flakka crisis, but the lessons from the 2015 outbreak can still be applied today. Whereas almost all flakka sold globally was manufactured in a single lab in China, Chinese fentanyl is produced in thousands of facilities across the country, complicating the Chinese government’s ability to crack down on producers.48 However, the flakka incident revealed that making public cases against Chinese drug traffickers can motivate the Chinese government to move quickly to control new NPS. According to Jim Hall, a drug abuse epidemiologist at Nova Southeastern University in Florida who met with Chinese officials about the flakka problem, the Chinese government “did not want to become known as a narco [narcotic] nation.”49 Dr. Hall suggests public pressure resulting from the sanctions contributed to the Chinese government’s decision to ban flakka, a strategy U.S. law enforcement could seek to replicate today.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!