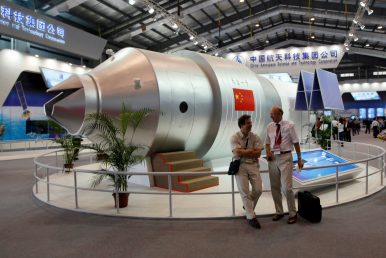

What China’s Upcoming Space Station Means for the World

Not many realize how impactful China’s upcoming space station will be, once it becomes operational by 2022. It is even more so given that the International Space Station (ISS) will remain operational only up to 2024, after which its funding will run out. By 2025, then, China will be the only country on earth with a permanent space station.

Bai Mingsheng, chief designer of China’s first cargo spacecraft Tianzhou-1, in an interview to China Central Television, stated that “China might be the only country that will run a space station in the foreseeable future. We could invite other nations to carry out experiments on [our] space station, making it an international scientific platform for all humankind.”

On May 28, China issued a call for all United Nations members to participate in its upcoming space station for the peaceful use of outer space in cooperation with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). Simonetta Di Pippo, director of UNOOSA, stated in an interview to Xinhua,“This is an agreement which will allow the entire world to use, for scientific purposes, the China Space Station when it will be ready… it’s the first time it is open to all member states.”

China’s invitation to all UN member states to participate in scientific experiments abroad its space station is clearly a dig at the United States. In 2011, a spending bill passed by the U.S. Congress included a clause that prohibited any scientific cooperation between China, NASA, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). The clause states that NASA and OSTP are prohibited “to develop, design, plan, promulgate, implement or execute a bilateral policy, program, order, or contract of any kind to participate, collaborate, or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company.” It also prevents NASA facilities from hosting “official Chinese visitors.”

During my visit to China in 2016 to interact with Chinese space policymakers, academia and students, I asked them about the 2011 U.S. congressional ban. Almost all argued that such a ban actually galvanized space research in China and improved their indigenous capacities. Chinese academics specializing in outer space specified that soon the world will be depending on China to establish a presence in outer space. This development, by default, would force the United States to cooperate with China. China’s Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with UNOOSA adds credibility to such a claim and affords it powerful agency in the construction of regulatory regimes in outer space.

In my several interactions with the space community in the United States, there is a tendency to underplay Chinese space developments as things the U.S. achieved decades ago, with China only now catching up. However, this kind of narrative obviates China’s growing space expertise, including in the domain of outer space resources. Consequently, when significant advancement is registered by China, space policy makers in the United States are taken by complete surprise.

For instance, in 2016, in a first, Chinese scientists demonstrated abroad the SJ-10 that mouse embryos could develop in outer space. Professor Duan Enkui, the principal researcher for the experiment, from the Institute of Zoology affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), stated, “The human race may still have a long way to go before we can colonize space but, before that, we have to figure out whether it is possible for us to survive and reproduce in outer space like we do on Earth… now, we have finally proven that the most crucial step in our reproduction-early embryo development-is possible in outer space.” Professor Aaron Hsueh, who specializes in reproductive and stem cell biology at Stanford University echoed Duan: “This represents an important milestone in human space exploration…One small step for mouse embryos, one giant leap for human reproduction.”

The growing importance of aerospace for China can be inferred from the fact that China’s space scientists are now being conferred important political jobs by President Xi Jinping. For instance, the former general manager of the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASTC), Ma Xingrui, was made governor of Guangdong, China’s largest economic province, in 2016. Xu Dazhe, administrator of the China National Space Administration (CNSA), was given charge of Hunan at the same time. This trend continued in 2017 with Yuan Jiajun, former China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) president, appointed acting governor of Zhejiang province, Xi’s own power base. In the past, local Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders were awarded these plumb posts.

Significantly, in CCP circles, the “spirit of aerospace” is listed along with the “spirit of the long march.” Consequently, China’s space sector will stride higher with the full backing of the CCP and the technological capabilities to show for it.

China’s ambassador to the United Nations, Shi Zhongjun, in a May 28 statement stated, “The China Space Station belongs not only to China, but also to the world.” As mentioned earlier, in cooperation with UNOOSA, China is inviting public and private companies, universities, all UN members, and especially developing countries to submit proposals for conducting scientific experiments abroad its upcoming space station. This high-profile gesture offers China, influence and power.

China views its space initiatives through the lens of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and is especially keen to see countries along BRI enjoy the benefits of China’s space capabilities. While announcing April 24, 2016 as the first National Space Flight day (China’s first satellite, the Dong Fang Hang 1 launched into space on April 24, 1970), Xu Dazhe, then in his post with CNSA, specified that China views its international space activities as part of the Belt and Road, and aims to build Asia-Pacific focused space cooperation.

With such high-end outer space cooperation comes the power to craft alternate regime structures and norms. China is already creating an alternative system of norms and regimes, to include setting up dispute resolution mechanisms along the BRI. By taking initiative and leadership in space, where the future will include the private commercial sector, China has granted itself enormous leverage and visibility. It also entrenches the Chinese system of governance and ideologies into the domain of outer space — with other countries now trying to play catch up.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!