Racism and the Belt and Road in CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala

A comedy sketch on CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala, possibly the most watched TV show in the world, has caused widespread controversies and accusations of racism in China and elsewhere. Especially in the English-language media, overwhelming attention has been paid to the use of blackface in the sketch, titled “The same joy, the same happiness.” However, debating solely whether wearing blackface itself should be considered a manifestation of racism in the Chinese context can be misleading. It may distract us from engaging in a historically informed discussion on racial issues in China and reflecting on what is politically at stake in the geopolitical narratives of the Spring Festival Gala.

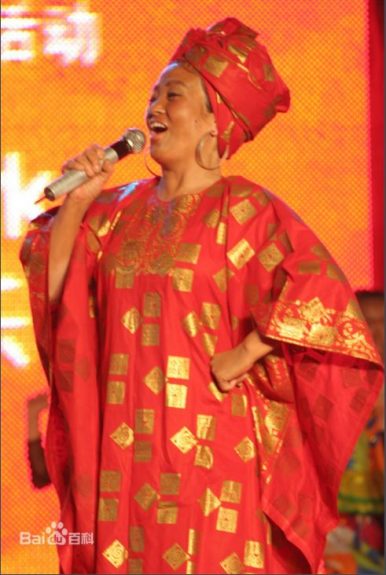

Celebrating the opening of the Chinese-built Mombasa-Nairobi rail line in Kenya, the skit itself tells a rather familiar story featuring the usual family drama and patriotic slogans typical of the CCTV show, except set in a different continent. A Chinese manager is approached by one of the train attendants he is responsible for training, Cari, who is under pressure from her mother to get married at the age of 18. The mother, played by Chinese actress and the director of the skit Lou Naiming, then appears on stage wearing blackface and with exaggerated body proportions. Even worse, she is accompanied by a monkey, which many believe is played by a black performer (though some claim otherwise). Following a series of confusions, the Chinese manager has to pretend to be Cari’s fiancé, until his real bride arrives. But when the mother finds out the truth, she is immediately convinced that her daughter should pursue her study in China instead of marrying early. Because, as we have guessed by now, she loves China.

A Bigger Problem Than Blackface and Fake Bottoms

Many defenders of the skit argue that the connection between blackface and racism is rooted in the specific history of racial relations in the United States and former European colonial powers. In these countries, blackface and the mockery of racial stereotypes in minstrel shows is associated with the systemic oppression of black people in history and the persistence of racism today. They insist that such history does not exist in China, and blindly interpreting blackface and stereotyping as racist is “Eurocentric.” Xu Wei, an anthropologist from the Institute for African Studies at Zhejiang Normal University, used the example of a beloved singer, Zhu Mingying, known for her outstanding skill in performing African dance and songs while painted in black in the 1970s, to make the point that no negative connotations are associated with wearing blackface or the black color in the “Chinese tradition.”

One objection to this argument would be that whether a practice of representation constitutes discrimination should be decided by those being represented. It is the impact, rather than the alleged good intentions, that matters. However, there are also good reasons for looking into the sociohistorical context that shapes understandings of race in China. And when we start doing this, it becomes clear that the assumption that China lacks experiences of racism and a history of racial thinking is wrong.

In his seminal book The Discourse of Race in Modern China, historian Frank Dikötter shows that racial thinking, which denotes a hierarchical categorization of humanity into distinct biological groups, had a profound influence among Chinese reformers and revolutionaries in the first half of the 20th century, and remained “an alternative form of discourse after the communist takeover.”

Revolutionary ideology in the Cold War era influenced the unique Chinese experience with non-black performers playing a black role. At a time when China’s relationship with the Third World – often referred to as yafeila (亚非拉), or Asia, Africa, and Latin America as a unified group of oppressed peoples – was guided by anti-colonial and anti-imperialist ideologies, cultural exchange was a means to enhance international comradeship. Under the advice of former Premier Zhou Enlai, the Oriental Song and Dance Troupe (东方歌舞团) was founded to introduce performing arts from the Third World to Chinese audiences and toured in many yafeila countries. As a member of the troupe, Zhu Mingying’s artistic practice and its reception needs to be contextualized in the political function of the arts and the dominance of revolutionary ideology at the time. In a 2011 interview, Zhu recalled that Premier Zhou had asked the troupe members to “imitate” the arts of the Third World the best they could and not to be “creative” in case foreign friends would take offense. She added that faithful imitation was a requirement of cultural diplomacy and she understood it as a political task.

The appeal of revolutionary ideology soon faded away in post-Mao China, and racism returned to the surface. In 1988-89, thousands of university students participated in demonstrations against African students in Nanjing and other cities (for more, see Michael J. Sullivan’s 1994 article in The China Quarterly and Barry Sautman’s article in the same publication, also in 1994). More recently, while the development of the Sino-African partnership is highly praised in mainstream media, reports about everyday discrimination experienced by immigrants of African descent are not rare, often resulting from a combination of ignorance and racial bias. Moreover, blatant racism is endemic on the internet (see also here). One needs only to take a look at the reactions to the criticisms of the Spring Festival Gala to get a sense of the pervasiveness of cyber racism.

The racial connotations of the “Africa skit” must be understood in relation to the reality of racism and racial thinking in contemporary Chinese society. It is racist not just because of its “insensitivity” to an unfamiliar cultural taboo, but also, more importantly, because it reinforces the prevailing racial and cultural stereotypes about a generalized land of “Africa” that can feed into real and verbal discrimination. Therefore the related groups would be adversely affected.

The Spring Festival Gala: More Than an Entertainment Show

Even if a private citizen may be excused for their “insensitivity” on the grounds of ignorance, CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala (SFG) is fundamentally different. For more than 30 years, it has been run annually by the official mouthpiece of the central government and the Chinese Communist Party not only to entertain, but also to communicate government policies, national pride, and moral values to millions of viewers on their most important holiday. The SFG is as political and educational as it is entertainment (if it’s entertaining at all).

In a previous study, media scholar Xiao Wang surveyed a total of 475 performances from 13 SFGs, and found that 56.2 percent of the performances sampled contained the theme of political propaganda and national pride, 45.9 percent contained the theme of promoting cultural values, and 32.4 percent fall into the category of social education. Note that one performance may feature more than one theme.

Comedy sketches and xiangsheng (or crosstalk) are considered “language-based performances” in the SFG system, in contrast to performances based on music and dance. These language-based performances play a particularly prominent role in promoting officially-endorsed moral values, such as filial piety, mutual help, and patriotism. Recent years have seen an increase of discriminatory content in this part of the show, including mockery of women who do not meet a narrow standard of beauty.

Sexism is also present in the “Africa skit,” whose director apparently thought the best way to represent the achievement of the railway project was through displaying and judging the physical attractiveness of female car attendants. At one point, the Chinese male superior examines the appearance of these carefully selected attendants, who flew from Kenya one month in advance for rehearsal, and asks the audience to join in the masculine gaze: “Aren’t they beautiful?”

It is the official and educational nature of the SFG that makes these explicitly discriminatory contents especially disturbing.

Geopolitical Imaginaries of the Belt and Road in the CCTV Galas

Lastly, as cultural geographers have noted, the annual gala is also an important venue for literally performing and reproducing China’s geopolitical imaginings.

Performances about the Belt and Road initiative, or BRI, have been a SFG staple since 2015. Most of them are songs and dances, and are historically oriented. In other words, while the BRI is proposed as a development and investment strategy for the present and future, the propagandizing strategy targeted at the domestic audience places a strong emphasis on ancient glories and the Sinocentric worldview of the past.

In another controversial section of the 2018 edition, Shan Jixiang, director of the Palace Museum, introduced to the audience a map titled “Landscape Map of the Silk Road” (丝路山水地图) as a “national treasure” finally returned home. However, internet users soon pointed out that the map was originally titled “Mongolian Landscape Map” (蒙古山水地图) and was made before the term “silk road” was coined by German geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen. Shan went on to explain that the map “proves that we Chinese already had a clear understanding of the route of the Silk Road as early as in the mid-16th century,” while the actual age and geographical scope of the map are disputed. The display of the map and the staged ritual of its “returning home” serve to perform a specific geopolitical imaginary: The Belt and Road Initiative has its historical root in a reimagined Sinocentric world order, which continues to mark the uniqueness of the modern Chinese nation.

Screenshot of “Tianshan Friendship.”

A comedy sketch from the 2017 edition, “Tianshan Friendship (天山情),” and “The same joy, the same happiness” are the only two BRI-related performances dealing directly with infrastructural projects – one in Xinjiang, the other Kenya. It is worth noting that “Tianshan Friendship” was the first comedy sketch led by ethnic minority actors in the 35-year history of SFG. The representation of ethnic minorities in SFGs has been extremely simplistic, homogeneous, and orientalist. It usually takes the form of a medley of traditional dancing and singing from different ethnic minorities packed into a few minutes. But this comedy sketch, which could have told a story about ethnic minorities from their perspective for the first time, offered no counternarrative.

The similarities between the “Xinjiang skit” and the “Africa skit” are striking. Both open with a dancing performance that appears “exotic” to the eyes of Han Chinese majority. To highlight the exoticness of essentialized cultural others, the Uyghur farmer has a donkey that can bow, and the “African mother” is accompanied by a monkey. Both skits revolve around a Chinese railway project wholeheartedly loved by the local people. The Uyghur farmer was once saved by his “Han brother,” and the Kenyan mother was once saved by a Chinese medical team. In short, both stories turn economically and geostrategically driven infrastructural investment into a glorified and moralized relationship between the altruistic saver/donor and the grateful saved/recipient.

Do these narratives reflect the actual Chinese engagement with Africa or Xinjiang policies? Obviously not. Instead, the skits reflect how the central government likes the domestic audience to think about these issues, at least in part.

While official discourse of the China-Africa partnership emphasizes “mutual benefit,” and the principle of equality for ethnic minorities is enshrined in the Chinese Constitution, these condescending depictions of the relationships and essentializing representations of cultural others are doing the very opposite. Their effect may also be the opposite of the alleged good intentions.

As Dikötter wrote about paternalism as a source of prejudice in Mao’s China: “Mao’s assistance to Africa reinforced the negative image of Africans as passive recipients of the fruits of higher civilizations, and intensified popular discontent at wasting wealth on Africans when many Chinese lived in extreme poverty.” It may come as no surprise that this mentality still hasn’t lost relevance in the present time, when Chinese companies are gaining huge profits in and from the continent.

Let us be reminded that anti-Muslim Han supremacism and anti-black racism are on the rise in the cybersphere. The reductionist, patronizing, and essentializing representations of ethnic and foreign relations in CCTV’s Spring Festival Galas are unlikely to counter that trend, and instead contribute to it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!