More than 40 per cent of the breadwinners for recent millionaire migrant households in Canada appear to have exited the country, although many left families behind there, according to new census data that illustrate the extent of a widespread phenomenon among rich Hong Kong and mainland Chinese immigrants.

Many millionaire migrants are exiting Canada but leaving their families behind there, census reveals

More than 40 per cent of the breadwinners for recent investor immigrant households no longer live in Canada, a phenomenon common among rich Hong Kong and mainland Chinese emigrants

PUBLISHED : Thursday, 21 December, 2017

Overall, only 52.6 per cent of the 52,507 investor migrant households that moved to Canada between 1986 and the May 201

6 census still had their original breadwinner, or “principal applicant”, living in Canada, according to the South China Morning Post’s analysis of the data.

Some of those have likely died – since the census data stretches over 30 years – but among recent arrivals the phenomenon is still striking.

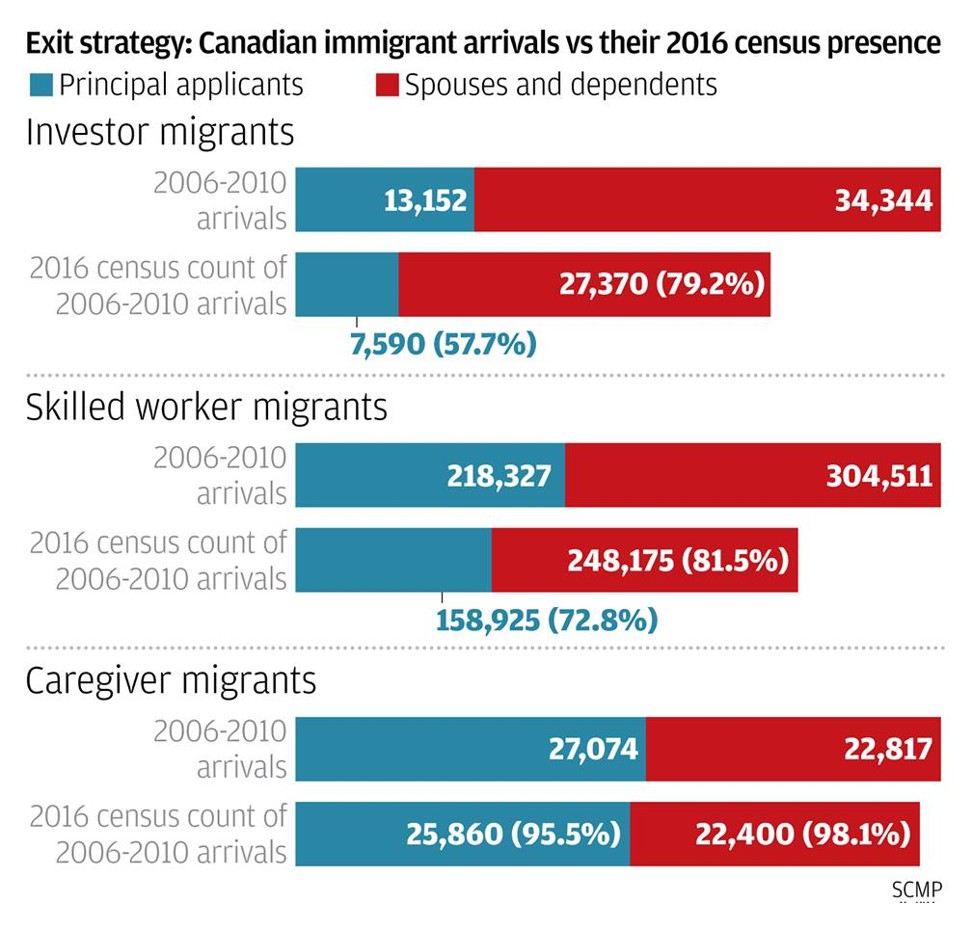

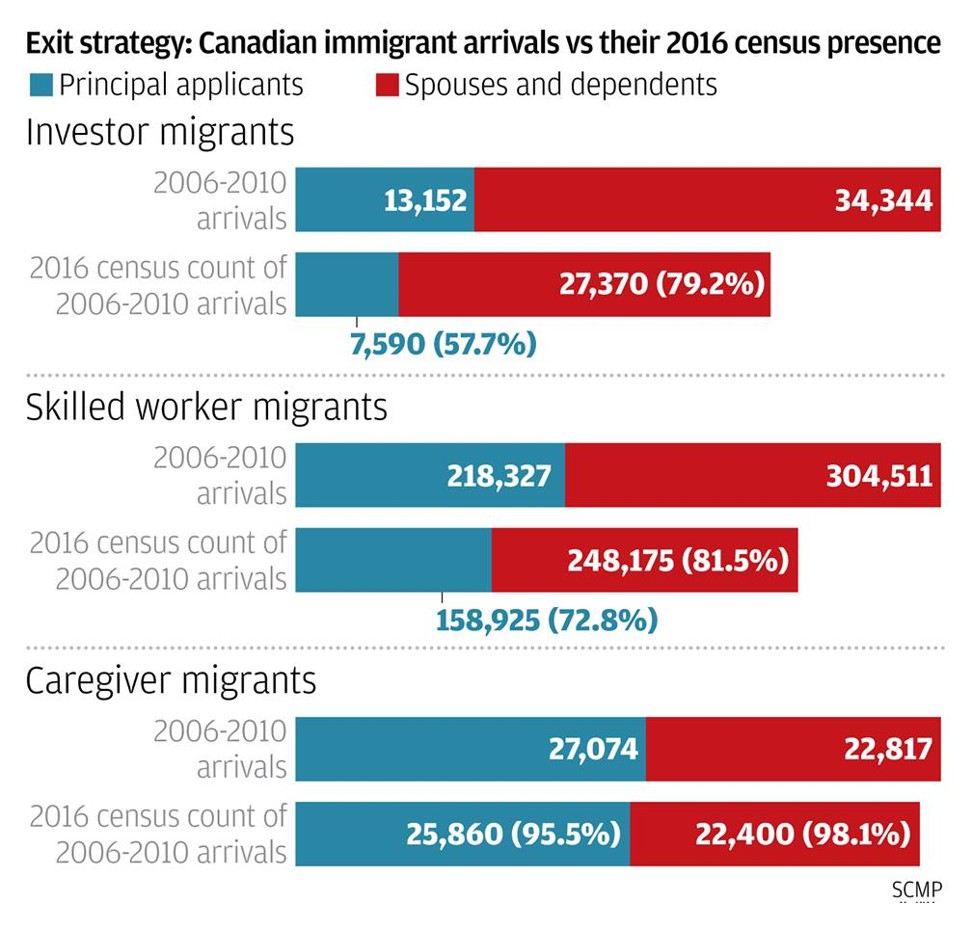

From 2006-2010 – the most recent census period for which comparable immigration arrival data exists – 13,152 households arrived under the federal and Quebec investor programmes for millionaire migrants. But by the 2016 census, only 7,590, or 57.7 per cent, of the original breadwinners remained.

By contrast, 79.2 per cent of their spouses and dependent children were still in Canada.

Comparing the census figures, released in October, with pre-existing arrival data helps illustrate both the large scale of reverse migration among the rich, and their tendency towards “astronautism”, in which immigrant households remain in Canada but are supported by absent, foreign-earning breadwinners.

Why do millionaires move to Canada, then leave?

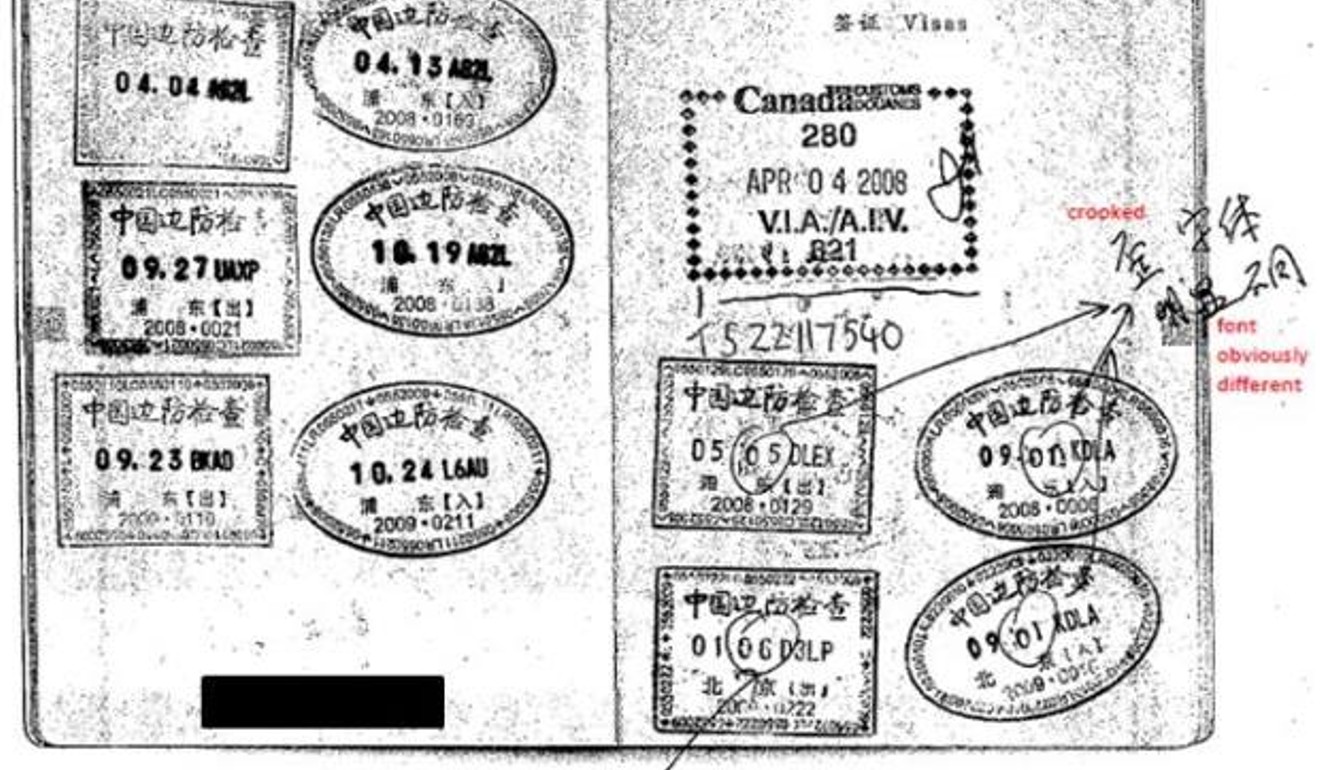

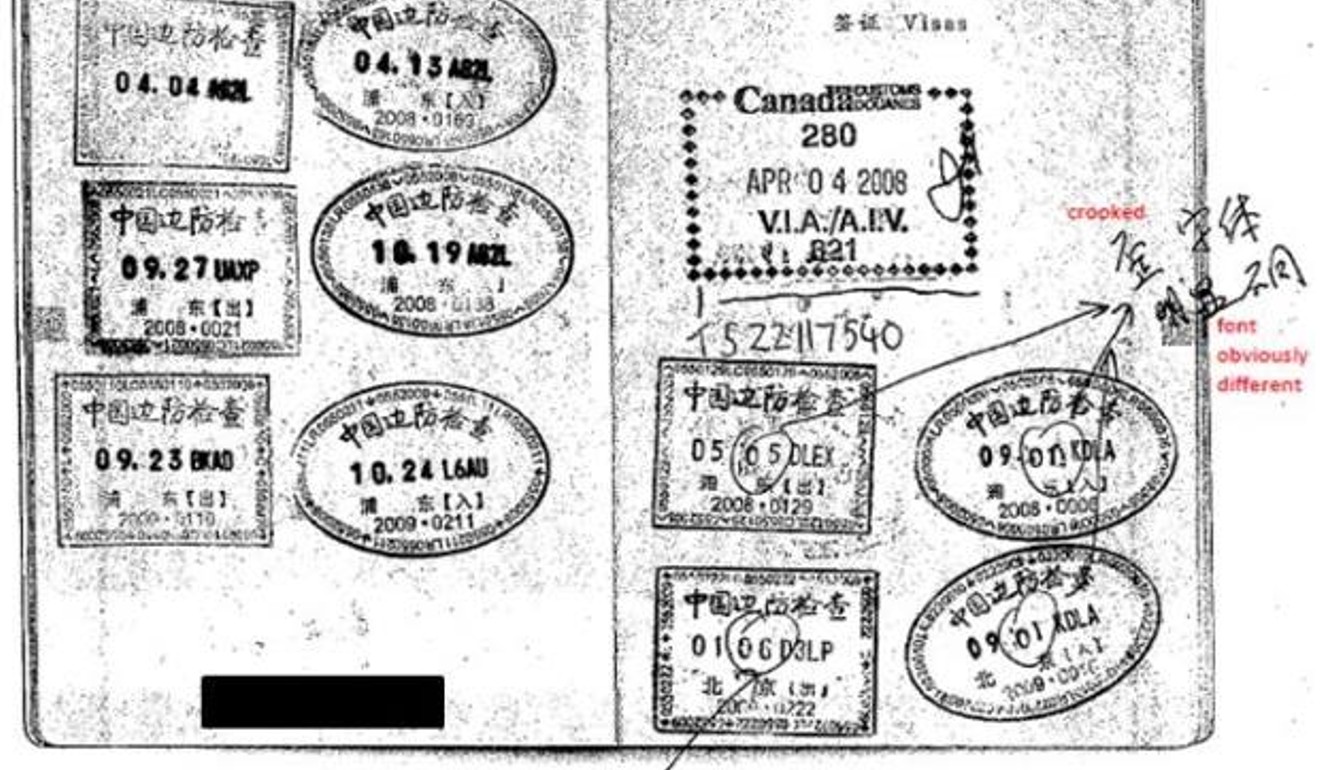

The phenomenon of reverse migration has previously been associated with tax evasion and immigration fraud – in 2015, the biggest immigration fraud case in Canadian history was exposed in Vancouver’s courts, involving 1,200 rich Chinese immigrants who falsely claimed to still be living in Canada in order to meet residency qualifications for citizenship.

It also helps explain the chasm between home prices and domestic incomes in Vancouver, where most investor migrants initially settle.

But Dr Justin Tse, an assistant professor at Northwestern University’s Asian American Studies Programme, who has studied astronautism among Vancouver’s Hong Kong immigrants, said breadwinners who exited were not necessarily acting nefariously but were maximising their family’s “economic potential”, since their employment and business prospects were likely inferior in Canada.

That observation is supported by plenty of statistical evidence. According to a 2014 evaluation by Canada’s immigration department, 65.9 per cent of investor migrants spoke neither English nor French at time of admission, and those who stayed as tax residents declared extremely low levels of income.

The report showed bread-winning millionaire migrants’ average taxable income from all sources peaked at C$19,500 three years after arrival, but fell sharply to C$15,800 after 10 years – among the lowest for any immigrants.

For families, the upside of astronautism was “the perception that as a unit, you can acquire more capital”, said Tse.

While absentee breadwinners may be separated geographically from loved ones and assets in Canada, the family as an economic unit remained whole, so long as “the money keeps flowing within it”.

Homes were acquired in Canada, and retained in their country of origin. When breadwinners left Canada, said Tse: “They’re not selling the house. They need the house here in Canada, and for it to be lived in.

“Some of this [real estate buying] might be speculative [but] chances are you won’t have an arrangement where the house in Canada is not lived in.”

Tse agreed that the astronaut arrangement was more prevalent among the rich. “You have to have the means to get out, and the means to return.”

For example, investor migration has required a net worth of C$1.6million, and a willingness to hand over C$800,000 as an interest-free five-year loan to the federal or Quebec governments.

And the new census data does indeed indicate the astronaut phenomenon to be much more prevalent among rich immigrants than others.

For instance, among recent (2006-2010) skilled worker migrants – the biggest category of economic migrants – 72.8 per cent of principal applicants were still in Canada according to the 2016 census, along with 81.5 per cent of their spouses and dependants. Among immigrants who arrived on caregiver visas in the same period, 95.5 per cent of principal applicants remained, along with 98.2 per cent of their spouses and dependents.

The downsides of astronautism

But transnational arrangements come with potential negatives, both for the families and society.

For absentee breadwinners, “the downside is the loss of ‘emotional capital’ … you might be increasing your financial capital, but the ability to engage with family on an intimate level decreases,” said Tse.

To some children, it even felt like an “invasion” when parents returned from sojourns outside Canada, he said.

According to a 2013 paper published in Global Networks: A Journal of Transnational Studies, Tse and co-author Dr Johanna Waters found that children in astronaut families experienced “fragmented” parental supervision, and sometimes resented “parents treating them as if they were incapable of either practical or emotional independence”.

As to the downside for society, Tse said: “Let me put this diplomatically – I don’t think people in these transnational arrangements are thinking very much about society. They are thinking about how their families can maximise the arrangement.”

For instance, “schools where these kids are going have to pitch in more, not just with the education of the students, but the emotional labour that goes into raising an adolescent”.

The failure to fully commit to Canadian society could represented a pushback against outside structures, in favour of the sovereignty of the family unit, Tse suggested.

“In Hong Kong, they felt colonised by China. In China, they feel there’s this government apparatus they need to hide their money from. In those situations, these people are behaving strategically.”

Both the federal and Quebec IIPs were dominated by Hong Kong immigrants in the run up to the 1997 handover, and by mainland Chinese since then. The federal IIP was halted in 2014, but the QIIP continues to operate; according to Hong Kong immigration firm Yelo Consulting, 66.5 per cent of last year’s QIIP intake was Chinese.

The phenomenon of out-migration has been well known in official circles, if not its precise scale. The 2014 immigration department evaluation said “increasing rates of out-migration after five years (especially among investors) may indicate a relationship with obtaining citizenship … a share of these immigrants wait to obtain Canadian citizenship to move out of the country.”

But it is not possible to reliably calculate what proportion of extant investor migrant households in Canada lack original breadwinners, based on the new census data – since it does not show how many households the remaining spouses and dependants represent.

The proportion, at the time of the census, was at least 19.2 per cent, assuming all extant families were perfectly intact except for the breadwinner. However, it could have been as high as 47.4 per cent, depending on how many households consisted of, say, spouses only or children whose parents had both left. The true figure lies somewhere in between.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!