Chinese Maternity Tourists and the Business of Being Born American [or] Canadian

Inside the Homeland Security crackdown on deluxe services helping Chinese women have American babies

May 12, 2015

Fiona He gave birth to her second child, a boy, on Jan. 24, 2015, at Pomona Valley Hospital in Southern California. The staff was friendly, the delivery uncomplicated, and the baby healthy. He, a citizen of China, left the hospital confident she had made the right decision to come to America to have her baby.

She’d arrived in November as a customer of USA Happy Baby, one of an increasing number of agencies that bring pregnant Chinese women to the States. Like most of them, Happy Baby is a deluxe service that ushers the women through the visa process and cares for them before and after delivery.

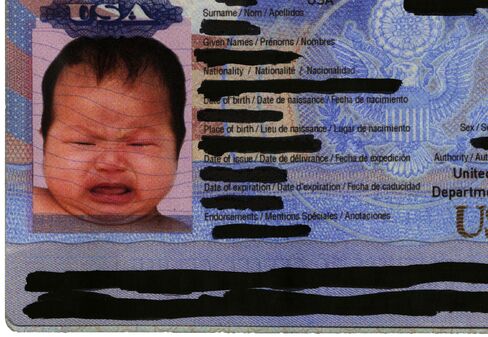

There are many reasons to have a baby in the U.S. The air is cleaner, the doctors generally are better, and pain medication is dispensed more readily. Couples can evade China’s one-child policy, because they don’t have to register the birth with local authorities. The main appeal of being a “birth tourist,” though, is that the newborn goes home with a U.S. passport. The 14th Amendment decrees that almost any child born on U.S. soil is automatically a citizen; the only exception is a child born to diplomats. He and her husband paid USA Happy Baby $50,000 to have an American son. If they had to, she says, they’d have paid more.

After the birth, He observed yuezi, the traditional month of recovery for new mothers. She, her mother, and her 2-year-old daughter stayed in Rancho Cucamonga, a city about 40 miles east of Los Angeles. Her apartment, in a complex with a pool, fitness center, and mountain views, was rented by USA Happy Baby. Her nanny was supplied by USA Happy Baby. She ate kidney soup and pork chops with green papaya prepared by a USA Happy Baby cook. She secured her son’s U.S. birth certificate, passport, and Social Security card with USA Happy Baby’s assistance.

He’s daughter was born in America as well. He and her husband, educated in Britain and from prosperous families, hoped to send their children to an international school in Shanghai that admits only foreign students. When the kids turn 21 they can petition for green cards for their parents, too.

It was all going well, until four men knocked on the door of He’s apartment on Feb. 23. They said they were fire department inspectors responding to a complaint about someone barbecuing on the balcony. She hadn’t been cooking outside. The men asked to see the adults’ identification. Then they asked the ages of her children. “I felt very weird then,” He says. “I wondered why they were asking me about my children when they came to ask about barbecue.” Afterward she called Phoebe Dong, who ran USA Happy Baby and lived nearby. “I said I didn’t feel safe. She said not to worry.”

A week later, five men from Homeland Security Investigations, the sheriff’s department, and the fire department arrived. At first He thought they’d come from the homeowners’ association. Then she saw the bulletproof vests and handguns. They showed her a search warrant. She recognized the translator from the previous visit. “Then they asked me a lot of questions, and I became nervous,” she says.

The HSI agents told He she wasn’t in trouble. That turned out to be only sort of true. They were investigating the owners of USA Happy Baby—Dong and her husband, Michael Liu—for suspected tax evasion, money laundering, and visa fraud. Although it’s legal to travel to the U.S. to give birth, it’s illegal to lie about the purpose of a visit—or coach someone to do so. For two hours the agents gathered documents, including the family’s passports, and made copies of He’s e-mails and texts. “They took my son’s immunization record, even the paper I used to record his milk time,” she says.

Then two men from the IRS showed up. They asked why He had flown from Shanghai to Las Vegas instead of Los Angeles. She told them friends had warned her that customs officials are tougher in Los Angeles. The IRS men didn’t look very happy with her answers. “After they left, I thought I had a very serious problem.”

He spoke in early April at the San Gabriel (Calif.) office of her lawyer, Long Z. Liu, on the condition that she not be identified by her full Chinese name. She says Fiona is her American name. He, 29, looked like she’d dressed hastily that morning. Her hair was pulled back; she wore no makeup. She spoke softly and quickly, alternating between English and Mandarin. She was often teary during the two-hour conversation, especially when talking about tensions in her family. Neither He’s parents nor her in-laws thought it was worth the trouble to come to the U.S. She wasn’t angry at USA Happy Baby; she mostly seemed bewildered by her predicament.

Homeland Security and the IRS have been investigating the growing business of “birth tourism,” which operates in a legal gray area, since last June. The industry is totally unregulated and mostly hidden. Fiona’s apartment was one of more than 30 baby safe houses that HSI agents and local law enforcement searched in Southern California that day in March. They came with translators and paramedics, almost 300 people in all. The investigators focused on three agencies—USA Happy Baby, You Win USA Vacation Resort, and Star Baby Care—using a confidential informant, undercover operations, and surveillance, according to three affidavits.

On March 3, Homeland Security agencies searched more than 30 baby safe houses.

Photographer: Jae C. Hong/AP Photo

Dong and Liu’s home was searched, too. Agents found close to $100,000 in cash. “We were running a serious and legit business,” Dong says. “We believe in the justice system in the U.S.” Liu referred questions to his lawyer, who didn’t respond. Kevin Liu, the lawyer for Star Baby Care, says: “There’s nothing to hide, and we’re cooperating with the investigation.”

No one knows the exact number of Chinese birth tourists or services catering to them. Online ads and accounts in the Chinese-language press suggest there could be hundreds, maybe thousands, of operators. A California association of these services called All American Mother Service Management Center claims 20,000 women from China gave birth in the U.S. in 2012 and about the same number in 2013. These figures are often cited by Chinese state media, but the center didn’t reply to a request for comment. The Center for Immigration Studies, an American organization that advocates limiting the scope of the 14th Amendment, estimates there could have been as many as 36,000 birth tourists from around the world in 2012.

Homeland Security declined to discuss the investigation because it is ongoing, but Claude Arnold, the agent in charge, says: “Visa fraud is a huge vulnerability for the country. These women allegedly lied to come have a baby. Other people could come to do something bad. We have to maintain the integrity of the system.” After the raids, which were covered by local media, agents received dozens of tips about other possible “birth hotels.”

The U.S. and Canada are the only developed countries that grant birthright citizenship. For those who believe U.S. immigration policies are too generous, birth tourism has become a contentious issue. “It’s like somebody giving birth in your living room and saying they’re part of your family,” says Ira Mehlman, the spokesman for the Federation for American Immigration Reform.

Legislation to abolish automatic citizenship was introduced into the House of Representatives this year, as it is every couple of years. The Republican leadership doesn’t seem interested, though.

“Some people say these families are taking advantage of a loophole,” says Emily Callan, an immigration attorney in Virginia who’s written about birthright citizenship. “If it was a loophole you could close it, but changing the 14th Amendment would be drastic. This isn’t a loophole or a technicality. It’s an unintended consequence.”

After the March raids, 29 Chinese mothers and relatives were designated material witnesses and ordered to stay in Southern California until the federal court decided they could leave. Fiona He moved from her apartment in Rancho Cucamonga to one in another part of the Inland Empire. “I want my children to have the best they can,” she says. “But I had no idea I would have this trouble. We didn’t hurt anyone. We just found an easy way to stay here to give birth. Is that wrong?” She was interviewed by a federal grand jury on March 11 with the promise of immunity if she continued to cooperate. No charges have been brought against any of the maternity services, nor have any promises been made to the women about their return home. As the weeks passed, He was feeling desperate.

In China, there’s nothing secret about birth tourism. It’s just another way to help a child get ahead. A hit 2013 movie, Finding Mr. Right, told the story of a woman who goes to America to give birth. That same year, 68 percent of people surveyed by Internet provider Tencent said they would want their child to be born in the States “if opportunity allows.” The maternity services maintain blogs and a steady patter of self-promotion. USA Happy Baby featured an ad with a baby lying on an American flag; Dong, the owner, regularly posted pictures of smiling customers, their newborns, and their U.S. passports. “The moms must be missing the time at our maternity center. It was real fun. Everything was taken care of. You lived like a ‘queen,’ ” read a post on social media by another service, called Enchong.

In China, there’s nothing secret about birth tourism. It’s just another way to help a child get ahead. A hit 2013 movie, Finding Mr. Right, told the story of a woman who goes to America to give birth. That same year, 68 percent of people surveyed by Internet provider Tencent said they would want their child to be born in the States “if opportunity allows.” The maternity services maintain blogs and a steady patter of self-promotion. USA Happy Baby featured an ad with a baby lying on an American flag; Dong, the owner, regularly posted pictures of smiling customers, their newborns, and their U.S. passports. “The moms must be missing the time at our maternity center. It was real fun. Everything was taken care of. You lived like a ‘queen,’ ” read a post on social media by another service, called Enchong.

Enchong, which isn’t part of the Homeland Security investigation, is well known in China. One Saturday in late March a dozen potential clients sit in a conference room at the Wuhan Convention Center, a former Communist Party hotel that’s benefited from a sleek renovation. Coco Zhai is an Enchong executive and, like many in the industry, was first a client. She is wearing a traditional Chinese dress and carrying an Hermès purse that, she tells attendees, was a present from her boss.

As Zhai explains, the first step to becoming a birth tourist is to obtain a tourist visa from a U.S. consulate in China, usually in the early months of pregnancy. U.S. consular officers have discretion in granting visas. They don’t have to turn away a pregnant woman who may give birth in the U.S., nor do they necessarily have to allow her in. If a woman is asked about her plans, she has to tell the truth. There’s already a new phrase in use among potential birth tourists: cheng shi qian, or “honest visa application.” Zhai encourages this. She also recommends entering the U.S. through a city other than Los Angeles. “Las Vegas is really easy because everyone goes there to gamble, no matter if you’re a senior or pregnant,” she says. “If you cannot cross the border, we cannot make money.”

If a woman says she’s traveling to give birth, the consular and customs officers may request proof that she can pay for her hospital stay. (The same would be asked of anybody seeking medical treatment in the U.S.) “Keep every single one of your invoices as evidence that you didn’t use the public charge,” Zhai says, referring to Medicaid. “If you have receipts with big sums, such as a watch worth tens of thousands, or a diamond ring, save those too.”

Enchong rents about 100 apartments in a sprawling complex in the Chinese community of Rowland Heights, about 25 miles east of Los Angeles. Pheasant Ridge, or Pregnant Ridge, as some locals call it, is wooded and secure and within walking distance of grocery stores, a Target, and several Chinese restaurants. After the birth, Enchong provides new mothers five meals a day and all the baby formula and diapers they need. The company that runs Pheasant Ridge, Arnel Management, declined to comment.

All the maternity centers boast of their success helping customers get visas and pass through customs. Zhai says that of Enchong’s 600 clients in 2014, no more than four were turned away at U.S. airports. The centers promise that in California there is no pollution, noise, or crowds—something that can’t be bought in China. They offer trips to Disneyland and SeaWorld; You Win, one of the services under scrutiny, took a group of husbands to a shooting range. The company motto was “Pass the love along.”

Toward the end of the two-hour presentation, Zhai is asked if Enchong could be the next service to be investigated. The raids and their aftermath are regularly reported on by the Chinese-language press. “Many maternity centers are scared,” she says, and some women have decided against going to America. The only change Enchong has made is that employees no longer go to U.S. government offices to collect passports and Social Security cards. They do that by mail. “We don’t want to rush toward the bullets, even though we don’t really know what the trouble might be.”

Fiona He used Enchong to have her first baby. When she was planning her second stay, she opted for USA Happy Baby because it offered housing with fewer pregnant Chinese women around. She wanted the quiet.

On March 3, Homeland Security agencies searched more than 30 baby safe houses.

Photographer: Jae C. Hong/AP Photo

The investigation that brought agents to He’s apartment began 50 miles away in Irvine, with an anonymous tip about Edwin Chen’s business. Chen had gotten into the birth tourism industry after personal experience. His wife, Jie Zhu, came to the U.S. to have their son in 2011. Zhu live-tweeted the first hours of her labor to friends back in China. When the couple had a daughter a year later, she tweeted from the hospital again. They decided to stay in California and help other Chinese to expand their families on American soil.

Chen opened American Angel 8 and, in January 2013, advertised online: “Give birth to an American baby. Start a wonderful journey.” He offered two options: a $30,000 gold package and a $60,000 platinum package, which promised a U.S. visa for the mother and a U.S. passport for the child, round-trip airfare, a two-bedroom apartment, a hospital room with a view of the ocean, a nanny, and a seminar on buying property in the U.S.

By the fall of 2013, Chen and Zhu were bragging about their success. Zhu posted a picture of a diamond watch on Weibo, the popular Chinese microblogging service. “The world’s only Jaeger-LeCoultre diamond watch, worth $400,000. Saw it in a magazine. Now am touching it. Thank you the rich moms staying at Angel 8.” In another post, Chen said he had bought the watch. (That turned out to be a lie: The maternity service business is lucrative, but not that lucrative.)

One of the rich moms was Dongyuan Li, a client who delivered twin girls in 2013. Afterward, she and her husband, Qiang Yan, made Chen an offer: They would fund a new maternity service in exchange for a majority stake. Chen would manage operations in California; Li and Yan would oversee recruitment in China. Chen shut down Angel 8 and, with Li and Yan, opened You Win USA Vacation Resort in December 2013.

Six months later a man in Los Angeles contacted Chen, saying he needed to help his pregnant cousin in China come to California to give birth. The new client and his “cousin” were actually Homeland Security agents.

According to an affidavit filed by HSI, the agent in China was told by a You Win “trainer” to apply for a U.S. visa with someone who travels regularly and wouldn’t raise suspicions about the purpose of the visit. If she didn’t know anybody, the trainer would supply someone for $9,600. “If the story is convincing and she is good-looking, then the success rate will be pretty high when she goes for the visa interview,” the trainer said. Concocting the story was included in the price. The undercover HSI agent got her visa and made plans to fly to the U.S. Sometime after that, Chen told his client that he might make as much as $2 million in 2014.

You Win’s customers stayed at the Carlyle at Colton Plaza, a gated luxury apartment complex in Irvine. Chen didn’t know it, but the Carlyle also happened to be down the street from a Homeland Security office. Agents could see it out their windows.

Otherwise, the Carlyle seemed like an ideal place for a baby hotel in 2014: It was new, and it wasn’t full. You Win rented at least 12 apartments and converted one into a communal kitchen and dining room. If the women didn’t want to eat there, uniformed chefs delivered their meals. The complex has poolside cabanas, an outdoor fireplace, a fitness center, and a lounge. Apartments rent for $2,800 to $4,300 a month. Homeland Security agents say that several other birth tourism operators may have used the Carlyle, too. The management company, Legacy Partners, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Two highly regarded hospitals are nearby. You Win suggested that the women choose doctors who could deliver babies there. According to the companies’ Chinese-language websites and lawyers for the women, the doctors usually insisted on being paid in cash for prenatal care and delivery. The families often took care of the hospital bill with cash, too, and seemed to receive a discounted rate because of it. The cost of a natural delivery was around $4,000; a caesarean section, $6,000.

You Win also drove the women to South Coast Plaza, which is filled with luxury boutiques. They bought classic saffiano purses at Prada, the sparkly Abel shoes at Jimmy Choo, lingerie with rhinestones at Victoria’s Secret. They were regulars at Chanel and Coach. All the shops employed Mandarin speakers.

Chen and Zhu were sleeping in their apartment in Mission Viejo when HSI agents knocked on their door early on March 3. The agents questioned Chen about alleged visa fraud and tax evasion for about two hours. The agents froze Chen’s bank accounts and seized Zhu’s Mercedes. They took the notebook where Chen recorded client information and his passport. Chen and his wife are permanent residents. The affidavit alleges they got their green cards through sham marriages in Las Vegas; Chen won’t comment on that.

Photographer: Getty Images

That morning, agents also questioned Dongyuan Li, who lives in a gated community outside Irvine. Among the assets they seized were 10 gold ingots, which she kept in a safe deposit box at her bank. (Their value hasn’t been determined yet.) Neither Li nor her husband could be reached for comment.

“We did what everybody else was doing,” Chen says, speaking on behalf of his wife. “There are no so-called standards.” He denied allegations of visa fraud, saying that You Win outsourced that part of the business to agents in China. “Had I known this industry is not allowed, I wouldn’t have touched it. But everybody said this is a gray area.”

After the raids, You Win shut down. The Carlyle sent eviction notices to the 11 apartments You Win had been renting, says Ken Liang, an attorney representing seven of the Chinese women. “The government said the women could stay in a detention center. No one was interested in that offer.” The doctors, who were paid in advance in cash, continued their care.

Liang says his clients didn’t lie about their pregnancies. “They were told by travel agents to wear loose clothing, but answer truthfully when asked. It could be seen that wearing loose clothing is evasion—but that’s a judgment call.” In the end, the consular officers didn’t ask his clients if they were pregnant, Liang says. All the women entered the U.S. in Honolulu, where customs officers did ask if a few were pregnant. They answered honestly and were let in.

“Birth tourism is a money-making opportunity,” says Liang. “The operators shouldn’t squander it.” He would like them to come out of the shadows and push for regulations. “This could have a long-lasting positive impact for the U.S. Bruce Lee was a birth tourism baby. Maybe we’ll get another genius out of it.”

Fiona He brought her daughter to the Riverside Federal Courthouse on April 7. Judge David Bristow was holding a hearing to determine when—or if—the Chinese women designated as material witnesses might return home. As the other women huddled around a translator, He walked in and out of the courtroom, distracted. One woman was still pregnant; another had a baby in a car seat. After three hours in court, they learned it was unlikely that any of them would be allowed to leave soon. On the courthouse steps, the women were distraught. The men were smoking. Fiona He remained at a distance. “I’m disappointed in the system,” says Liu, her lawyer. “These women are being treated like criminal defendants, not witnesses.”

A week later, He fled to China with her mother and two children on China Eastern Airlines flight 586. Five other women and their relatives—10 material witnesses in all—left on other flights out of Los Angeles International Airport. The women had been given back their documents and traveled under their own names. “This was very embarrassing for everyone, including me,” Liu said a day after learning of He’s departure. On April 26, Liu made public a statement from He. She said her grandmother, who raised her, was terminally ill, and she had no choice but to return to China. She said she would come back to the U.S. to testify. “As a responsible person with integrity, I always keep my promises. I do not intend to make an exception this time.”

On April 30, He officially became a fugitive. The government charged He and nine others with alleged obstruction of justice, contempt of court, and visa fraud and issued warrants for their arrest. “It’s pretty ironic,” says Liu. “She did so much to get passports for her kids. Now they can come to America anytime. But she probably can never come again.”

—With Bloomberg News

—With Bloomberg News

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!