In Sudan, China focuses on oil wells, not local needs

June 25, 2007

Paloich, South Sudan – Li Haowei’s girlfriend gave him a silver ring when he left Liaoning, his home province in China, nine months ago. Before he boarded the flight to Sudan, Mr. Li had never even left Liaoning before. “You are so lucky,” his girlfriend said, then, enviously.

“I was happy to go abroad and see the world,” says Li, an accountant for Petrodar, a multinational oil consortium. “But I did not know enough to know I did not want to come here.”

Paloich is not a particularly welcoming place. The heat surrounds and suffocates you like a plastic bag. The dust in the dry season sticks to your eyelashes and fills your nostrils. Mosquitoes buzz in your ears relentlessly.

Li is making three times the salary he would at home. But he misses his girlfriend, he says, twisting his ring around. He misses Liaoning. He misses real Chinese food.

Sometimes he can’t sleep. Fear of malaria is a constant. He broke down crying when he read a tender letter from his mother last month. He does not like it here.

The local Sudanese are not too keen on his presence here, either.

Sudan’s oil production averages 536,000 barrels a day, according to estimates by the Paris-based International Energy Agency. Other estimates say it is closer to 750,000 barrels a day. And there is an estimated 5 billion-barrel reservoir of oil beneath Sudan’s 1 million-square-mile surface, almost all of it in the south of the country, an area inhabited mainly by Christian and animist black Africans who fought a 21-year civil war against the Arab-dominated Muslim government of the north.

The vast majority of this oil, 64 percent, is sold to China, now the world’s second-largest consumer of oil. And while neither Khartoum, China, nor Petrodar release any statistics – this is generally believed to be an oil deal worth at least $2 billion a year.

China’s National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) is the majority shareholder in both Petrodar and the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company, two of the biggest oil consortiums in Sudan.

CNPC has invested billions in oil-related infrastructure here in Paloich, including the 900-mile pipeline from the Paloich oil fields to the tanker terminal at Port Sudan on the Red Sea, a tarmac road leading to Khartoum, and a new airport with connecting flights to Beijing.

But they have not invested in much else here.

Locals live in meager huts, eating peanuts with perch fished out of the contaminated Nile. There is no electricity. A Swiss charity provides healthcare. An American aid group flies in food and mosquito nets. Most children do not go to school. There is no work to be found. Petrodar, for one, has its own workers – almost all of whom are foreigners (mostly Chinese, Malaysians, and Qataris) or Sudanese northerners. The consortium hires Paloich residents only rarely, for menial jobs.

It’s a picture of underdevelopment not unusual in Sudan’s semiautonomous south. While some pockets – like the regional capital of Juba and the bigger towns of Rumbek and Wau – have seen some economic revival since the signing of the 2005 peace agreement, the majority of the south remains mired in abject poverty.

Locals blame their lot on oppression by Sudan’s Islamist government and the long war with the north. But they also blame the Chinese.

“[The Chinese] moved us away so we would not see what was going on. They were stealing our oil and they knew it,” says Abraham Thonchol, a rebel-turned-pastor who grew up near Paloich. “Oil is valuable and we are not idiots. We were expecting something.”

US-based Chevron was the first oil company to arrive here, setting up operations in the 1980s. “They employed us,” says Mr. Thonchol. “We helped with the drilling, drove them around, and worked as cooks. “

The second group of oilmen to show up was not as benevolent, say many locals. Thonchol’s cousin, Peter Nyok, a 6-foot, 6-inch, member of the Dinka tribe with traditional lines carved on his forehead and six missing front teeth, says it took a while for locals to differentiate between Westerners – and the Chinese that came later. “They looked like whites to us. We could not detect any difference, except, maybe, that they were shorter,” he says. “But then we found they behaved differently.”

Chased out by civil war in the mid 1980s and ’90s, and later kept away by pressure from human rights groups, Chevron and other Western companies left the oil fields for others. Canadian Talisman Energy, faced with a divestment campaign, was forced to sell its 25-percent stake in the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company in 2002.

Chinese firms were more than happy to fill the void.

But the Chinese operations were marked “from the beginning,” by a “deep complicity in gross human rights violations, scorched-earth clearances of the indigenous population,” says Sudan activist Eric Reeves, a professor at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. Giving expert testimony before the congressionally mandated US-China Economic and Security Review Commission last August, Mr. Reeves claimed the Chinese gave direct assistance to Khartoum’s military forces which, in turn, burned villages, chased locals away from their homes, and harmed the environment while prospecting for oil.

Brad Phillips, director of Persecution International, an aid group working in South Sudan, has seen the destruction firsthand. “The Chinese are equal partners with Khartoum when it comes to exploiting resources and locals here,” he says. “Their only interest here is their own.” He would love to see the Chinese sponsor a school here, he says, or a clinic, or an agricultural program, or “anything for the people.” But there is nothing like that in sight. Just miles of desolate land.

“The Chinese simply do not care about us,” says Martin Buywomo, Paloich’s mayor. “They have no contact. They never even came to my tent to pay respects. They think we are lesser people.” A member of the Shilluk tribe who attended British mission schools, Mr. Buywomo puts down the worn copy of George Eliot‘s 19th-century classic “Silas Marner” he is reading and continues sadly. “We see them in their trucks but they overlook us. If they saw us dying on the road, they would overlook us.”

Buywomo rearranges the Chinese-made plastic pink flowers on his desk. “This is colonialism all over again.”

THABO MBEKI, for one, might not rush to correct such an impression. Last December, the South African president – whose country is Beijing’s largest trading partner on the continent – cautioned against an unequal and “colonial relationship” with China.

Across the border, in neighboring Zimbabwe – a country that can ill afford to offend the few friends it has – Trevor Ncube, a respected newspaper publisher, devoted a recent issue of his Zimbabwe Standard to whether doing business with China was “merely swapping our old colonial master for a new one.”

Perhaps most worrying for the Chinese is the grass-roots reaction to their advances in the southern African nation of Zambia.

China, the world’s largest copper consumer, has pledged $800 million in investments in Zambia, one of the world’s largest copper producers.Beijing has written off nearly $8 million of Zambia’s debt and announced the establishment of a showcase free-trade zone which, according to China’s ambassador to Zambia, will create tens of thousands of jobs.

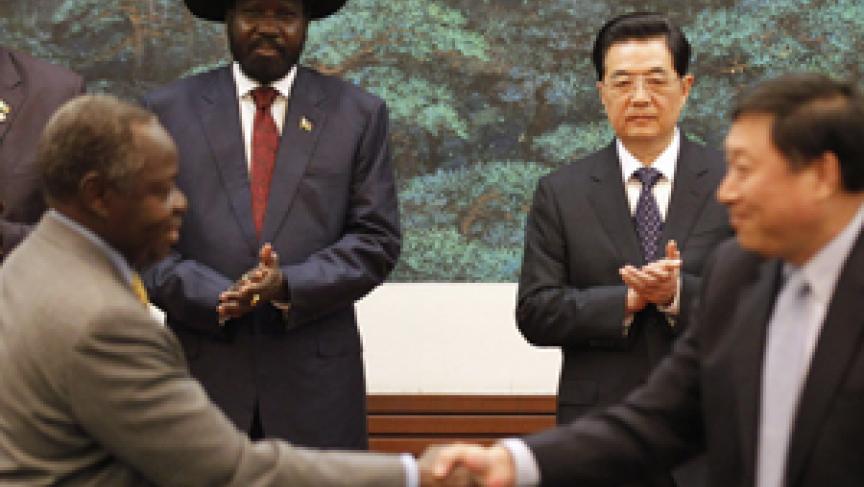

Nonetheless, in the lead-up to Zambia’s Sept. 28 elections, presidential candidate Michael Sata turned lack of safety at Chinese owned mines (50 Zambian mine workers were killed by an explosion in 2005) into a major campaign issue. Mr. Sata fumed about what he called the plunder of the country’s mineral wealth and disregard for the environment – and promised to kick out the Chinese and recognize Taiwan if he won. He did not. But a few months later, Chinese President Hu Jintao cancelled a visit to the Zambian copper-mining town of Chambishi due to fear of mass demonstrations against him there.

This negative image of Beijing as a neo-colonizer could not be further from the way China – a country never involved in either the colonial “Scramble for Africa” of the 1800s or the African slave trade – wants to be perceived here.

“Over the last half decade, the Chinese and African people have built a deep friendship in the course of the struggle for national liberation, development, and rejuvenation,” then Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing told reporters after Mr. Hu’s Zambia mine visit was canceled. “African friends, from leaders to civilians … called China a ‘brother of Africa,’ an ‘all-weather friend,’ and the ‘most important partner,’ ” waxed Mr. Li.

The Chinese, who, unlike the European powers who came before them, have no direct rule over any population here and negotiate the terms of their stay with the ruling government, say abuses of power are exceptions to the way they do business.

“We always encourage Chinese enterprises to be in equal-footed cooperation with their African counterparts, to abide by local laws and regulations,” Liu Guijin, China’s new special representative to Africa told journalists in Beijing in April. “If they did something not so pleasant, that is not consistent with government policy.”

Xu Weizhong, director of the department of African studies at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, a government think tank in Beijing, refines this point. First of all, he says, many Chinese enterprises are independent and cannot be controlled. “Now even state-owned enterprises have room to maneuver … and will sometimes refuse government policies. This is a dilemma for the Chinese government.”

But furthermore, he says, while China is indeed aiming to be a fair business partner, the definition of what “good practice” might be should not be set by outsiders. “The Chinese government respects African rules and regulations if there are any, [but] it is less willing to respect rules that Western governments impose on African issues,” he states.

Petrodar accountant Li dismisses the whole debate, calling the stories about stealing oil, degrading the people and the environment, and becoming new age colonizers “Ali Baba tales.”

“I am here to make money. My company is here to do the same,” he says. “I know this is a very poor and insecure place, but I am not responsible for fixing all the things that are wrong in Sudan,” he adds, not quite understanding the complaints. “That’s life. That’s business.”

• Peter Ford contributed to this report from Beijing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!