China's predetermined politics leave public disinterested

|

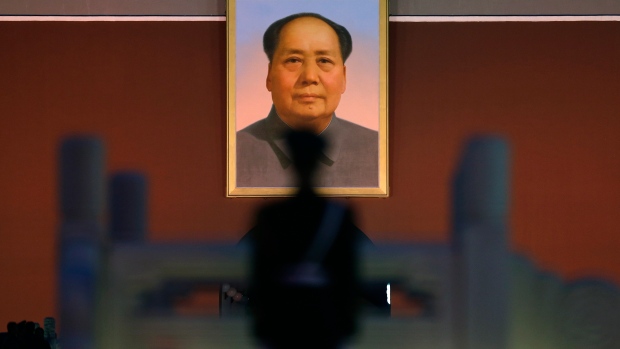

| Chinese paramilitary policeman stands guard at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China Wednesday, Nov. 7, 2012. (AP / Vincent Yu) |

Janis Mackey Frayer, CTV Asia Bureau Chief

Published Wednesday, Nov. 7, 2012 12:09PM EST

Published Wednesday, Nov. 7, 2012 12:09PM EST

China is undergoing a political transition that happens only once every decade and, when it is complete, one of the world’s most influential countries will be ruled by new generation of leaders.

Its new president, Xi Jinping, was today anointed Chairman of the Communist Party and Supreme Leader. Mr. Xi’s ascent is no surprise here, as he has been the heir apparent to outgoing president Hu Jintao since 2007.

Coincidentally the Communist Party’s 18th Congress, known here as shi ba da or “18 Big”, will get underway within hours of the U.S. re-electing its president. The slate here will not be determined at the ballot box by Chinese of voting age, but behind the sealed doors of the Great Hall of the People by 2,270 elite Communist Party delegates.

There will be no breathless reporting of results on television specials as they are all largely predetermined. It means the vast majority of Chinese claim little interest in the process because they have absolutely no hand in the outcome.

“Politics is none of our business,” declared a Chinese friend earlier this week. “Everything is mi mi (secret) so what is the point to care?”

China’s new leaders will determine the course of the country and its important economy for the next decade, so in that sense, much of the world is curiously watching.

Mr. Xi will head the all-powerful Standing Committee of the Politburo, comprised of nine men (there is the slim possibility of one woman), that will balance expectations here with modest reforms while preserving party power and stability.

That last task may prove the trickiest so there is little chance of dramatic change any time soon. Mr. Xi and his comrades will not be officially installed to rule until the National People’s Congress convenes in the spring. For now, hints of “reform” manifest in subtle ways, like party communiqués with fewer references to the late Chairman Mao Zedong, a pioneer of Chinese Communist ideology.

“Gradually the Party is moving away from Mao,” historian Zhang Lifan said in an interview. “But if they do so too quickly that can cause problems, too.”

For the Congress, China’s government has left few details unattended in primping its desired appearance of calm and unity. Around the capital, it has ordered a refreshing of flower displays and food inspections at hotels. There are traffic controls in place and trucks are restricted from parts of the city. Balloons, kites and even pigeons are banned from flying. Kitchen knives have been pulled from some store shelves and boats were ordered out of park ponds by Beijing’s Traffic Authority to “ensure water safety.”

The security measures seem less a hedge against the spectre of attack or violence than the perennial fear of dissent. Internet censorship has ramped up, meaning Internet speeds have slowed down as they comb content. Taxi drivers have been ordered to remove backseat window cranks to prevent passengers from tossing anti-regime leaflets. Activists were told -- or outright forced -- to leave the city until the Congress is over.

“At first they were very nice. But then as soon as I got in a car with them they put a black hood over my head,” said rights activist Liu Shasha, who was taken from Beijing to her hometown in Henan Province on Oct. 22, according to Reuters.

Amnesty International says more than a hundred other writers, bloggers, lawyers and dissidents were told to leave the capital over the past few months. Their phones are tapped, email is monitored and, in some cases, policemen are assigned to watch closely over them.

“We are witnessing the same old tactics of repression,” said Amnesty’s Roseann Rife. “Respecting human rights would be a genuine show of strength by the incoming leadership.”

To dissuade petitioners -- the people who come from all parts of China to register their grievances -- an undisclosed number of police are on duty. They are fortified by more than a million security volunteers to quash “bad behavior” as China’s rulers aim to choreograph stability and enforce it.

Its new president, Xi Jinping, was today anointed Chairman of the Communist Party and Supreme Leader. Mr. Xi’s ascent is no surprise here, as he has been the heir apparent to outgoing president Hu Jintao since 2007.

Coincidentally the Communist Party’s 18th Congress, known here as shi ba da or “18 Big”, will get underway within hours of the U.S. re-electing its president. The slate here will not be determined at the ballot box by Chinese of voting age, but behind the sealed doors of the Great Hall of the People by 2,270 elite Communist Party delegates.

There will be no breathless reporting of results on television specials as they are all largely predetermined. It means the vast majority of Chinese claim little interest in the process because they have absolutely no hand in the outcome.

“Politics is none of our business,” declared a Chinese friend earlier this week. “Everything is mi mi (secret) so what is the point to care?”

China’s new leaders will determine the course of the country and its important economy for the next decade, so in that sense, much of the world is curiously watching.

Mr. Xi will head the all-powerful Standing Committee of the Politburo, comprised of nine men (there is the slim possibility of one woman), that will balance expectations here with modest reforms while preserving party power and stability.

That last task may prove the trickiest so there is little chance of dramatic change any time soon. Mr. Xi and his comrades will not be officially installed to rule until the National People’s Congress convenes in the spring. For now, hints of “reform” manifest in subtle ways, like party communiqués with fewer references to the late Chairman Mao Zedong, a pioneer of Chinese Communist ideology.

“Gradually the Party is moving away from Mao,” historian Zhang Lifan said in an interview. “But if they do so too quickly that can cause problems, too.”

For the Congress, China’s government has left few details unattended in primping its desired appearance of calm and unity. Around the capital, it has ordered a refreshing of flower displays and food inspections at hotels. There are traffic controls in place and trucks are restricted from parts of the city. Balloons, kites and even pigeons are banned from flying. Kitchen knives have been pulled from some store shelves and boats were ordered out of park ponds by Beijing’s Traffic Authority to “ensure water safety.”

The security measures seem less a hedge against the spectre of attack or violence than the perennial fear of dissent. Internet censorship has ramped up, meaning Internet speeds have slowed down as they comb content. Taxi drivers have been ordered to remove backseat window cranks to prevent passengers from tossing anti-regime leaflets. Activists were told -- or outright forced -- to leave the city until the Congress is over.

“At first they were very nice. But then as soon as I got in a car with them they put a black hood over my head,” said rights activist Liu Shasha, who was taken from Beijing to her hometown in Henan Province on Oct. 22, according to Reuters.

Amnesty International says more than a hundred other writers, bloggers, lawyers and dissidents were told to leave the capital over the past few months. Their phones are tapped, email is monitored and, in some cases, policemen are assigned to watch closely over them.

“We are witnessing the same old tactics of repression,” said Amnesty’s Roseann Rife. “Respecting human rights would be a genuine show of strength by the incoming leadership.”

To dissuade petitioners -- the people who come from all parts of China to register their grievances -- an undisclosed number of police are on duty. They are fortified by more than a million security volunteers to quash “bad behavior” as China’s rulers aim to choreograph stability and enforce it.

Read more: http://www.ctvnews.ca/world/china-s-predetermined-politics-leave-public-disinterested-1.1028349#ixzz2BaXITZYA

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments always welcome!